The network was desperate for new hits was an exhibition resulting from a month long summer residency project at Dog Park in Christchurch by Julia Lomas and Leah Mulgrew, two Auckland based artists. Presenting works by Kah Bee Chow and Campbell Patterson, the exhibition appeared as a momentary stasis in a continuum of conversation and influence around the curators’ ongoing and dedicated reading of television. In particular, The network was desperate for new hits addressed how our appropriation and interpretation of cultural material affects us as individuals.

Campbell Patterson’s 30 minute digital video Zopi 2 (2014), consists of precise edits from season two of American legal drama The Good Wife, sliced together into short constructed sections. His editing cuts out dialogue, leaving the characters on the cusp of language, animated within choked gestures or poised facial movements, neutralised into ambiguities. Tension is palpable, a pasted on thickness. Narrative is melted into cosmetic surfaces as a mass of appearances, and the actors become abstract reflections of their constructed surroundings.

Still from Zopi 2 (2014) Campbell Patterson

Patterson presents TV narrative as a range of textures and codes, and through this the serialised manners of TV narrative is rendered as brittle. In fracturing narrative and temporality, and rearranging their forms, Patterson raises questions about a receptivity to something that, previously, made ‘sense’, both intensifying and confusing the ways we understand and read these structures.

Long black leaders separate each sequence of edits, what we expect from the beginning or end of a film becomes a repeated pattern that we return to again and again. The blackness (a further obstruction to establishing a sense of narrative development) is both a lengthening out (prolonging the final frame within each sequence, exaggerating the suspense until the next edited sequence), and a quickening of time (a performance of the agonizing wait we might feel between episodes). Patterson may be making us sweat. In experiencing the imposed structure of Patterson’s video work as a collectively shared/felt infliction, I considered the artist’s attempt at inhabiting the settings he is investigating. By collapsing each episode into sequences of glances, gestures and actions, we experience an entire 13 episode season in half an hour. Meanwhile, Patterson has given himself over to watching the full season in real time. His body enters the work; and watching the resultant edit with all its thwarted expectations is a likewise exhausting process.

Constraint, self-sacrifice and absurd repetition are recurrent motifs within Campbell Patterson’s practice. In Patterson’s second work in the exhibition, Carpet (2014) the performance of neuroses, how this forms/informs the art object, and narratives of bodily histories are also present. Constructed from pieces of muesli bar, each is carefully placed to form a floor ‘painting’ reminiscent of Aboriginal Dreamtime paintings. Within the act of building up a pallette of many very small pieces of oat and chocolate lies a sense of a TV-induced, functional zoned-out-ness, a vortex that implicates televisual space and time, that becomes visible through the image of dream time, and bodily traces.

Installation view of Carpet (2014) Campbell Patterson. Image by Daegan Wells

In their essay You should have hired a professional to project manage the build published in Magasin (Feb 2013) Julia Lomas and Leah Mulgrew allude to a type of liberation within a particular kind of television viewing experience. Exploring the precarious relationships individuals have with desire and representation, they consider how we collectively interpret moments of importance and meaning by recasting images and moments as objects.

“In the sticky residue of caring about something a little bit too much…something about something else is revealed. To become an object though, a series breaks down into selected moments”[1], or perhaps we break down a series into an accumulation of ‘images’ that appear to testify to moments and events important in relation to a specific time and place. “Certain fictions, documenting and dramatising our ordinary aspirations, or grossly extending these into something quite unreal, become experiences of their own, with emotional pressures applied, these experiences become images, to be re-used, re-applied, re-made”[2].

Kah Bee Chow’s objects first appear indebted to these pressures; objects ‘pressed’ from these fictional spaces into the real space of the gallery. ‘Images’ to be made sense of through a formal and aesthetic language of television; approximations of objects of the interior spaces from popular series such as The Good Wife.

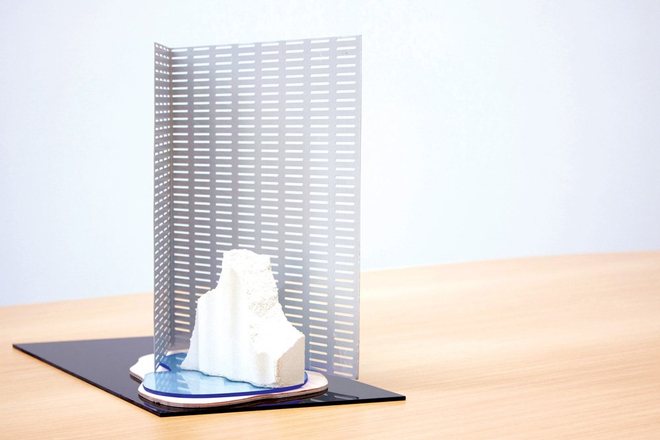

Installation shot of 山 水 (2014) Kah Bee Chow. Image by Daegan Wells

Each of these small sculptures is an assemblage of prefabricated materials; perforated chipboard, Plexiglas, cement, Styrofoam and plywood. Collages of commercial products and processes, they sit between surrealist sculpture and design object; oscillating between experiential and material; micro landscapes. Surfaces as simulations of space, flattening things to reduced forms, pattern, light and shadow, caricature design objects that themselves mimic real space, and the slick appropriation of the Zen garden within a law office as potent symbol.

Pairing readymades and sculptural assemblage with the spatially and temporally flattened-out world of television, these works incite potential to subvert their own premise, their literal flatness.

Subterfuge (penguin), 2014, a laser-cut Plexiglass form is thin black silhouette of an unfamiliar animal, recognisable as a penguin through its titling and the familiarity of its image via nature programmes. Its title also points to a duplicity, the possibility for images and objects to act out a deceit, for superlative representation to infer the death of the original. In an essay published in e-flux, A Thing Like You and Me [3], Hito Steyerl draws out how the materiality of the image and its display undoes the reality of that which is being represented, and the potential for identification and subjectivity within this; “…if identification is to go anywhere, it has to be with this material aspect of the image, with the image as thing, not as representation. And then it perhaps ceases to be identification, and instead becomes participation”’.

Kah Bee Chow’s work here appears in flow with information, of a shared understanding of cultural temporality, and in the leveling out of forms, flattening information, her work allows for a greater efficiency in appropriation. Her work evokes a sense of stasis within a transition, highlighting a self-obsolescence of contemporary culture and ephemera, and the potential to participate in endless Xeroxing, copying, re-staging, re-appropriation.

The exhibition of works is ‘contained’ within a constructed environment that, in a sense, presents Lomas and Mulgrew as curators of an ideological and imaginary enclosure. Evoking a design language lifted from the legal dramas they reference, Lomas and Mulgrew provide spatial conditions for the artists to push up against. An imposing boardroom table; plinths that follow dimensions of large filing cabinets; soft tones; large sheets of plate glass; modular office carpet occupy formal positions within the gallery, and delineate a ‘zone of fakery’[4] for the works to inhabit.

Installation view of The network was desperate for new hits (2014). Image by Daegan Wells

In the entrance to the gallery, next to the large plinths that support Kah Bee Chow’s baguette-Styrofoam lamp Craggy Assets (baguette lamp), is a framed screenshot from the supernatural/sci-fi drama Lost. The island in Lost hovers just out of frame as an invisible, authoritative presence, foregrounding an idea that environments and settings frame and determine our activities in ways that are not necessarily visible and explicit[5]. Within this space there is a convergence of scripted space, televisual space and the space of the gallery. Information pools together with various momentums and from various directions, swirling in a circulation of cultural appropriations and interpretations. Perhaps an immersive experience of overflow of information. It feels appropriate to describe this as a reconstruction of the experience of watching television, a merging of multiple positions, images and representations, an embodied temporality where an experience of their work may also be permeated by a sense of its persistent re-use and re-circulation.

1 Julia Lomas and Leah Mulgrew, We see each other in important places/You should have hired a professional to project manage the build – How television constructs images of selective pressures (memes for ourselves), Magasin, Feb 2013, ed. Ashin Raymond and Anya Henis

2 Ibid

3 Hito Steyerl, A Thing Like You and Me, e-flux journal 15, April 2010, ed. Julieta Aranda, Brian Kuan Wood, Anton Vidokle4 Julia Lomas and Leah Mulgrew, The network was desperate for new hits, exhibition text, Dog Park Art Project Space, Jan/Feb 20145 Ibid