Ōtākaro is indicative of a new sincerity in New Zealand art at the moment—a post-postmodern moment whereby artists are re-engaging with traditional myths in a manner that is both sincere and critical. In Ōtākaro Reweti and Te Tau draw upon their Māori heritage to collaboratively explore the narratives and identities associated with the river—interpreting them through a modern sci-fi lens to generate a mythology relevant to, and effective in, the twenty-first century.

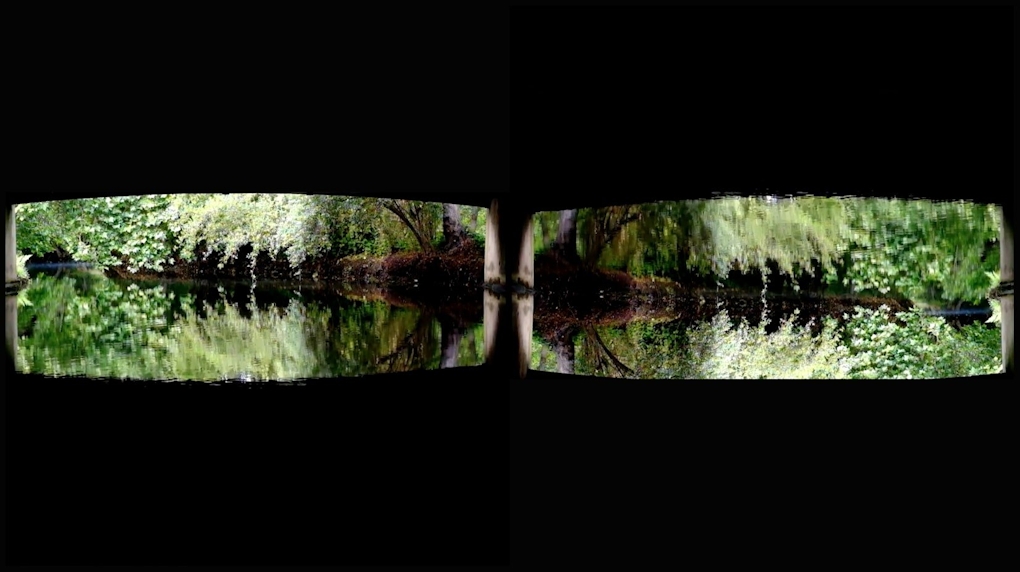

For their recent installation at The Physics Room, the artists presented a story rooted firmly in place. Working from the Dean’s Avenue bridge in urban Christchurch, Reweti took a single continuous 40 minute shot of the Ōtākaro (Avon) River during early dawn. Much like her earlier videos which used camera obscura techniques, Reweti used post-production to mirror and flip the image, re-presenting the original image as two screens in one.

The tale itself is a sci-fi story about a missing girl, space-time portals, and whitebaiting (a traditional practice of gathering schools of tiny fish that still occurs, albeit dependant on weather and tides, in the now polluted river). In the artist talk Reweti explained how the sci-fi genre lends itself well to Māori cosmology, giving the example of Maui’s super human abilities whereby he slows down the sun, to change time and lengthen the day. Thus, in Ōtākaro, different possibilities are entertained regarding the nature of time and space, allowing alternative conceptions of both the past and the future to be remembered or imagined.

Māori beliefs regarding the nature of colonisation are obviously not so sentimental, rather they tend to be critical, and as such they have been virtually erased from the national imagination.

The effect of the camera obscura technique complements the sci-fi theme. With one half of the projection reversed, time seemingly runs both forwards and backwards, and then turns in on itself again, as the reflection of the river bank in the water itself provides yet another mirroring effect. The two mirrored images of the river almost take on the look of a pair of eyes, through which we may peer into the alternative reality created by the artists: the river is where the reality we know so well in Christchurch converges with an alternative reality, and it is where the action of the plot takes place.

While Ōtākaro does ultimately have a point at which some of the questions developed throughout the narrative are answered, particularly regarding the missing girl, Emily—a sense of openness or wonder, rather than clear cut conclusiveness is the overall effect. This is partly due to the various different threads of meaning developed in the work that, when combined with the mirrored nature of the projection, create a sense of cyclical, rather than linear, unfolding of time.

The layers of meaning inherent to Ōtākaro are effected partly through the use of a different voice. Teanau Tuiono performs a subtextual narrative role, providing several interludes to the main story, which function to clarify its relevance. This secondary part of the script refers to aspects of physics, such as the theoretical possibility of the Einstein rosen-bridge, also known as a space-time wormhole. Such contextual information adds depth to the narrative: “Welcome to intersections in astrophysics and cosmo-genealogy… there are some Māori that face neither the past nor the future, and who will on occasion step completely off the track.” Here, the abstract reference to Emily’s disappearance, with regards to Māori mythology, is linked to Western science.

In conjunction with other parts of the main narrative, this subtext helps the installation subtly point out how predominant views of reality tend to both legitimise, and be shaped by, those with the most power in our society (in the New Zealand case, this is a postcolonial context driven by the instrumental rationality of Western science). However, the complexity of these power relations is not ignored. For example, the language used to perpetuate gender inequalities is intersected with those of the postcolonial. This can be seen when the protagonist, an astrophysicist, reacts to having her beliefs called “nonsense made up by silly little girls”: “Arsehole, she thought, he didn’t get to decide what was real.”

Still from Ōtākaro (2016) Bridget Reweti and Terri Te Tau, The Physics Room, Christchurch 2016

To engage with the creation of mythologies of place, is to consider collective identity and notions of homeland. It is to engage with the stories we consider collectively, as self-identifying "New Zealanders"(1), to be true about this place, about our home and who belongs here.

Both artists have engaged with the process of collective myth-making in the past. In particular, Te Tau has worked on projects that examine how modern surveillance modifies community behaviour, and explored strategies for resisting this. Her work has a focus on respecting and applying traditional forms of knowledge, in order to generate alternative epistemologies, or ways of knowing. The weaving of collective mythologies is a central theme accordingly, so her practice has included working collaboratively with other artists, to create something that could not have been accomplished when working as individuals. By researching, collecting and telling stories that have not be told, that might be somewhat invisible (such as women’s stories about war, or Māori stories about the place of Aotearoa), a form of resistance to hegemonic mythologies is generated throughout her oeuvre. It is here that a form of resistance to, or critique of, the reasoning and justifications for modern surveillance is situated in her oeuvre.

Similarly, Reweti’s work is firmly located in New Zealand narratives of landscape and Māori histories of the land. By critiquing postcolonial narratives about the New Zealand landscape her work is necessarily about myth, and in particular, landscape mythology–the classic trope of a Pākehā dominated national identity. Her work tends to have a focus on questioning these dominant postcolonial narratives of the New Zealand landscape, and offering alternative stories, and thus ways of knowing, the place of Aotearoa.

In order to disrupt dominant power relations (such as, but not limited to those between the (post)coloniser, and the colonised), an alternative landscape mythology has been imagined and articulated in Ōtākaro. This mythology reflects and embodies alternative beliefs about, and ways of knowing, the material world of landscape, compared to those promoted under colonial, and now neoliberal capitalist, ideologies. Such a collaborative engagement with the construction of collective mythology gives Ōtākaro its power, because to engage with myth, is to address the creation of what comes to be known, or believed, as truth in a society. This legitimising power of myth can be seen when one compares the mythologies surrounding the ongoing process of colonialism in New Zealand.

For European settlers, colonisation was understood, and is often still remembered, via a sentimental myth of New Zealand as terrae nullius — a place that supposedly deserved development into a new, more productive, rural idyll or Arcadia.(2) But, the meaning of this colonising process was very different for Māori, who were brutally disenfranchised in their own homeland. Māori beliefs regarding the nature of colonisation are obviously not so sentimental, rather they tend to be critical, and as such they have been virtually erased from the national imagination.

One only needs to look to current 100% Pure New Zealand branding to see how people are still absent in our most dominant, pristine and empty, landscape imagery—except for the odd tokenistic presence. But, as the Prime Minister of New Zealand, John Key said in 2012, we don’t actually take the idea of 100% Pure New Zealand seriously anymore. We cynically know it’s not true.(3) We know about the scale of environmental issues such as climate change and waterway pollution, because they are reported in the mass media on a daily basis.

As one of the most prominent critical theorists of our time, Slavoj Zizek, argues—today we are living under the ideology of cynicism. This is an ideology that fosters a lack of faith in our ability to imagine and articulate change(4) So while we are critically aware of the limitations of late-capitalist models of development, such as environmental pollution, we lack faith in our ability to create something better.

Today, we cynically know that 100% Pure New Zealand now only really exists in the hyperreal. Yet this myth of New Zealand as an empty and pristine landscape persists because it serves an instrumentally rational purpose of capitalist development in a now global free market (particularly relating to tourism and "clean green" primary products of the land). It persists because this purpose, or instrumental reason, has been prioritised over cultural criticism regarding environmental degradation—especially relating to our rivers—that has been, and still is, directed towards it. Thus the dominant (post)colonial myths of the empty landscape have been reified by a cynical late-capitalist ideology that promotes a belief that critique is futile: that there is no alternative.

Still from Ōtākaro (2016) Bridget Reweti and Terri Te Tau, The Physics Room, Christchurch 2016

The ability for art to foster a different form of belief, one that is not sentimental, nor cynical, but critical and sincere is where the power and relevance of Ōtākaro lies. People are central to the narrative in a way that disrupts the usual form of looking to the New Zealand landscape that we have become accustomed to. Rather than the tourist gaze towards an empty and sacred landscape, a landscape that affords experiences of the sublime for those willing to enter it, the landscape of Ōtākaro is inhabited by everyday people, such as a builder in his classic kiwi “all-weather” stubbies (shorts), and a gruff police officer who helps with the investigation into what happened to Emily. The sci-fi landscape of the river is not only where an alternative reality is constructed, but where everyday activities occur: “The girls had built themselves a mini wharf from raupo tied together with strands of harakeke. It was on the opposite side of the river under the willow tree, whose branches formed a curtain that hid the pier from passers by.”

Some of the river scenes are rather Romantic, in the sense that it is the site of both child’s play and a sci-fi fantasy world. But references to things such as the missing girl’s alcoholic mother, and another strange relative, prevent the plot from succumbing to the sentimental myth of New Zealand as a rural idyll. Similarly, the river is not the only place where the story unfolds—it is accompanied by urban sites such as the library, the residential red zone, the police station and the university. The river is set amongst a landscape that is real, rather than hyperreal: it is not separated from landmarks of our urban culture, but flows in and around it. Thus the dichotomy of nature and culture is broken down in Ōtākaro, pointing to the fluid nature of this socially constructed divide.

The way that whitebaiting is a central part of the narrative, highlights the practicalities inherent to the river. It is the site where a traditional method of collecting food is practiced. As a citizen of Christchurch, it is hard to ignore the fact that whitebaiting is becoming difficult due to the severe pollution of the river. This river degradation may likely be in the mind of the viewer, even though it is not addressed directly. But this is not necessary in order for Ōtākaro to be effective. Under the ideology of cynicism, we as an audience are already aware of environmental pollution. What the work needs to do in order to foster a critical awareness is not highlight that which we are already critically aware of, but foster that which we need to make this critical awareness effective: namely a faith in our ability to do something about it—a belief in the efficacy of critique. In the late-capitalist moment, faith is no longer relegated to that of the social opiate: the new sincerity is the radical new form of critique.