Hiona Henare’s commission for Matariki is titled THEY AIN'T WOKE YET (2023) and is a video installation that references historian Elsdon Best's 1919 publication The Land Of Tara and those who settled it, which recounts how Māori came to Te Whanganui-a-Tara. The film features actors Lawrence Makoare, Ratu Tibble, Tamai Nicholson, and Isis Bradley Kiwi. The work is currently being installed at Masons Screen, Te Whanganui-a-Tara Wellington, where it will be shown from 18 July to 28 August 2023.

Hiona Henare is an award-winning filmmaker with a strong indigenous lens. She is a two-time participant in Berlinale Talent, her films have screened at FIFO, imagineNATIVE and HIFF Hawaii, and her new short film I Am Paradise is featured in this year's Whānau Mārama: New Zealand International Film Festival (NZIFF) Ngā Whanaunga Māori Pasifika Shorts. Last year, her television series The Untold Tales of Tuteremoana screened on Whakaata Māori, which was produced with her tribe Muaūpoko and authentically filmed on land largely within her tribal rohe.

CIRCUIT'S 2023 Matariki curator Leo Koziol sat down with Henare to talk about what inspires her screen art and filmmaking, her journeys to the Amazon rainforest, and her experiences of working with award-winning directors.

Hiona Henare. Image by Mumu Moore.

Leo Koziol: Kia ora koutou, I'm Leo Koziol and I'm interviewing Hiona Henare as CIRCUIT's Matariki curator for 2023, through which I've worked with Hiona on a new moving image work for Masons Screen in Pōneke, Wellington. Kia Ora Hiona, what was the inspiration for THEY AIN'T WOKE YET, a video installation response to Elsdon Best's Land of Tara?

Hiona Henare: Elsdon Best wrote his journals from oral histories. This is public knowledge; so when he was receiving the information, he was also translating it into a digestible or prescribed narrative that Pākehā wanted to hear. There was a lot of information that was edited or deleted.

At the same time, we don't know how much of it is and isn't true. Well, we can figure this out, but we weren't in control of the lens or the storytelling back then, or the collecting or the research or the archiving of stories.

To answer your question, this piece that I've done, THEY AIN'T WOKE YET, is about dismantling, or that word that we all throw around, decolonising, the perception of what we think is true. That's really what this work is about. It's about putting a flag in the ground.

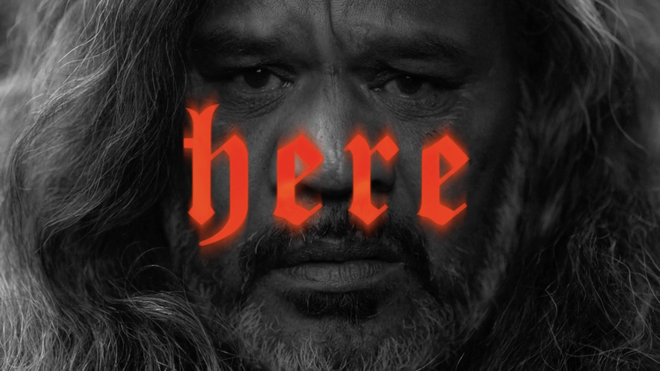

Still from Hiona Henare, THEY AIN’T WOKE YET (2023)

LK: Tell me about Elsdon Best and his book of stories about Whanga-nui-a-Tara.

HH: We all know Elsdon Best from history in Aotearoa. There's even a suburb named after him in Porirua. But what Elsdon Best is best known for in the Pākehā community is being an archivist or an anthropologist or a collector of stories. The consciousness amongst our Māori community is that he was a bit of a spinner, and he collected oral stories from our tohunga, from our chiefs, from our whānau, and he took it upon himself to edit or even delete what he received, which makes his work quite dangerous for, say, our Pākehā, for tauiwi in Aotearoa who read this stuff [and who] believe it to be true. Even for our whānau, who are disconnected from their whakapapa and want to learn about themselves, and all they've got is Elsdon Best's bullshit, really.

I guess my work is about challenging the narratives out there. I don't mean because we have this whole thing of trying to include our Māori history in our history books, which is really important. But if you know where the damage is done, through history and literature and where all sorts of racist and systemic things have happened, say, through science, education or even film, you know where these bullshit places are.

I think it's our responsibility to bring these issues to the surface. That's what I'm doing with this piece is to highlight the journals that Elsdon Best wrote entitled The Land of Tara and really put my spin back on his book. My style with my art is to look at the ironies of life and to reclaim what was lost.

LK: So this is an art installation that's going to go in Wellington CBD, is that part of it? The whole situational perspective of the artwork in a city built by colonists like Elsdon Best?

HH: This is something new for me, doing video art installation work, because I'm used to having a lot more time to tell a story and to build character arcs and a story world. But with [this] installation, I've really only got that moment of foot traffic walking past. And so in that, say, one or two minutes, what I really wanted the film to do is have a presence, at first glance. So I decided to go with a black and white grade, something inspired by the old Samurai films, Akira Kurosawa style. And that was to represent an older time, first of all.

And then I wanted my characters on screen to portray a kind of sadness, as if they were saying, "Yeah, it's really great that we have a Matariki day now, and it's really great that we've got a Māori CEO at the Film Commission. We've got a Māori director running the New Zealand School of Dance and the New Zealand Drama School."

"Well, it's really lovely that we get to have these Matariki festivals around Aotearoa now."

It took us a long time to reclaim that kōrero and to fight for even a day that's a celebration. A day every year that celebrates and marks the beginning of our ceremonial, customary traditions.

But my philosophy is we still can't be complacent about the things that we need to fix. And so with this story, because I am Muaūpoko and I do whakapapa to Tara and to Ngāi Tara, it felt that it was a good place for me to use this moment of attention that I can get from passersby to say something beautiful, radical, and contemporary.

Still from Hiona Henare, THEY AIN’T WOKE YET (2023)

LK: Tell me more about what has drawn you to move into the moving image art installation space.

HH: Moving into the multimedia and multidisciplinary installation space gives me a chance to have a lot more fun technically and creatively, working with the skills I have. As a filmmaker, one of the agreements I set in any project that I work on is that I edit my own first rough cut. This is to set the tone of my work, so I can hand that over to the editor, who comes in and uses what I've done as the foundation. The vision is there and they are able to maximise that.

One thing that I've learned as an editor, and also as a musician, is the importance of those skills in terms of being able to tell a story in an abstract or surreal or creative format. Knowing how to play with pacing and timing is really important for film—but when we talk about art installation it means that you can really be experimental and I think it's good for all filmmakers and artists to flex their experimental muscle.

LK: You most recently made a television series collection of films called The Untold Tales of Tuteremoana and you made them with your iwi. Can you talk about the process of working with your iwi on a film production?

HH: That project came about when the Tuia—Encounters 250 fund was set up to commemorate—not celebrate—Captain James Cook’s arrival in Aotearoa. There was a whole lot of funding that was up for grabs if you wanted to say something that was related to Cook. It was a tough decision for me to make because I knew that there was a lot of resistance out there in our Māori communities to take that funding, because in a sense it meant that you bought into that false narrative that Cook discovered Aotearoa. But when I really thought about it, I thought, "Well, I think it's more radical to take the money and do the opposite of what they want me to do with it."

So that's what I did. I applied for funding, I got in touch with my whānau, Muaūpoko and Muaūpoko Tribal Authority, and talked to them about the project that I wanted to make. I really wanted to tell our stories and to bring visibility to our Kurahaupō waka, which to me is more important than the Endeavour. But we're not going to get money [for that]. They're not going to put millions of dollars up so that you can tell a story about Kurahaupō or any waka.

Well surprisingly, we got the funding, but from there it wasn't an easy process. Working with my family who understand the story, they understand the tikanga, they understand the significance and the exuberance, and they understand all of this that's involved in seeing a film and representation. Of course we're Māori, so there was a lot of people to keep happy. That was probably the most challenging part of working with my iwi. But this project is the third film that I've done with my iwi, so they knew what they were getting into and that whatever I say I'm going to do, I'm going to do it [and deliver].

They trust me now to represent our whānau and our tūpuna tastefully and with mana. I guess at the end of it, for me, I came out a better person because I've had my whānau behind me every step of the way. For my whānau, it's good for them that they were able to be support me and be a part of these big epic projects.

I don't like those terms, the first this or first that [iwi-made film]. But what I can say for our whānau, it was a big deal because we're such a small whānau. And as I mentioned, we are the descendants of Tara. We're based in the Horowhenua, that's where Muaūpoko is. But our tribe is Ngāi Tara.

Still from Hiona Henare, THEY AIN’T WOKE YET (2023)

Still from Hiona Henare, THEY AIN’T WOKE YET (2023)

LK: What was the response from your people?

HH: One of the things that we all shook hands on, right from the get-go, was that our whānau were going to see the films before anyone else. And that was always something that I was always secretly excited about. Because this could be something quite frightening, to take your film home, to show your whānau who you don't know if they will or won't like it. In my case, I worked with my whānau each step of the way—they were involved, so there were no massive surprises.

We all got to celebrate. Not just the fact that we made films together, but to celebrate that we now have visibility out there, that people will know who we are because we've got Muaūpoko Tribal Authority right at the top of the film credits. And that was another thing that really mattered to me because I wanted to have that pride of, "Yep, I'm an artist and I'm a filmmaker. I'm also a wahine and I've done this with my iwi, yeah, with my whānau."

LK: The filmmaker Barry Barclay talked about Fourth Cinema and "Camera in the Community." Do you feel that your work is an expression of living the Fourth Cinema principles?

HH: Well, I hope so. When I met Barry Barclay and we both realised we had blood ties through our Ngati Apa and Kurahaupō whakapapa, it was a game changer for me. Fourth Cinema was a game changer. When I spoke about seeing this fund that was available around Aotearoa during the Tuia—Encounters 250 commemorations, Barry came to mind in terms of having an internal radical moment like, "Oh wow, this is great." So this money is for the commemoration of Cook's ship Endeavour and him arriving in Aotearoa but that's just one perspective. And if we're looking at the way that Barry Barclay approaches the lens and the camera and putting a lens or camera in the community, that was exactly what I did. I showed Cook arriving in Aotearoa from the shore. The rest of the trilogy worked backwards from that moment. I guess the genesis of this idea came from, "How do I use this money strategically to tell the other story, the fourth cinema redux?"

Still from Hiona Henare, THEY AIN’T WOKE YET (2023)

LK: Turning to another topic, last year you participated in a film arts residency with the award-winning Thai filmmaker Apichatpong Weerasethakul in the Amazonian rainforest. How has participation in that residency affected your art and filmmaking practice?

HH: First of all, in Apichatpong's cinema—slow cinema—it's all about past lives, it's all about the timeless time between. Well, there's no states with time. And that's the theory and creative process that Apichatpong works with. That's something that I was really drawn to, watching all of his films and being a little bit of a geek of slow cinema. And he's from Thailand, so we're all related, we're all from the islands. And there was just something about his way of storytelling that felt authentic and present for me. Everything's present.

So when I found out that he was holding a director film lab in the Amazonian jungle last year, there was just no way that I wasn't going to be there. It was a really busy time for me because I was preparing to shoot two of the three films for Tuteremoana. Literally two months before I was meant to start shooting, I saw that Apichatpong was holding a masterclass for directors in Peru.

I saw that it cost money. I saw that I would have to fly over to South America. But I just applied for it and then I went and shot my films. Later on, I found out that I had been selected and off I went.

Still from Hiona Henare, THEY AIN’T WOKE YET (2023)

LK: So what did you do there, in the Amazon?

HH: My time in the Amazonian jungle with Apichatpong was everything I thought it was going to be. Perhaps this was the connection I had with his cinema anyway. We were there to make a film with Apichatpong helping us and there were 50 filmmakers. And I was a little bit, "Well, how is this going to happen?" But it happened. He was sharing his sensibilities and his style of craft and film, but sharing it in a way where he wasn't teaching you how to be a filmmaker, instead he was teaching you how to think. That was the first thing for me.

Basically what Apichatpong did, and I think this is why it will be one of the highlights of my life, is [he showed us] his process, his quiet and gentle process about filmmaking. For the first week we were there, we didn't do anything technical. We didn't do anything with our cameras. We weren't even talking about a story. We were really just there to be in the jungle, to visit villages, to go and look at sites, and to meet communities and just get a sense of our environment, so that we could learn, we could listen and understand this part of the world that we'd all just flown into.

So that first week with Apichatpong, it was 5am meditation. It was walking through the jungle. It was meeting locals. It was sailing down the Amazon River. It was going to communities. That first week was really all about us adjusting and finding our feet and being able to embody the world around us.

Next, we started talking about, "Okay, now..." And that's where the scheduling came out. And that was really about, "So what we're going to do for the next five days is you've got to go away and think of a story based on anything that came to you while you had that week of just being and existing."

We each had a meeting with Apichatpong to run our story past him. He didn't do the executive producer thing, like, "I think..." or "I want..." or "I don't like..." or "Maybe he should do this," or "I don't understand." He didn't do anything like that. He was more interested in the stories that we were pitching, in how much of ourselves we were putting into the story. And I thought that was quite cool.

So after getting sign-off, you had four days to shoot. Then you had three days to edit your films. By the end of that edit, there was a screening of all the films and a big party in the middle of the jungle. That's definitely another highlight.

He [Apichatpong Weerasethakul] wasn't teaching you how to be a filmmaker, instead he was teaching you how to think.

Still from Hiona Henare, THEY AIN’T WOKE YET (2023)

LK: Then you returned to Aotearoa and you had a newfound interest in moving image artworks.

HH: When I was out there, the Wairoa Māori Film Festival had sponsored me with a camera, I had everything I needed. I was given a lot of memory space, everything that I needed to ensure that my camera wasn't affected by the humidity. Being in the jungle, making friends and stuff, we were all exchanging things like microphones, lenses, sound recordings, etcetera. I was shooting all the time, I was shooting so much without any rest, it's quite possible I lost my mind for a bit! I was watching the jungle, and the jungle was watching me—that kind of thing.

I had just come from the Wairarapa, from our natural bush there, from our natural ngahere. Going into the Amazon was like going into another forest or another jungle, it was quite [similar]. It was quite a smooth transition for me to be able to adjust, because some of the other filmmakers really struggled with being able to just land and be present. It was quite full on for them and intense being in nature. And when I say nature, it wasn't nature, it was nature.

So I shot a lot of stuff there. I guess that's the way that Apichatpong is, his wairua or his āhua. I think, if anything, that pulled out that creative side of me. When I came back to Aotearoa, I had the option of doing moving image or video art installations or films or just about anything I wanted. Perhaps that's more of a technical thing. If you know how to move between different mediums or storytelling platforms, if you can jump around, you should jump around.

Still from Hiona Henare, THEY AIN’T WOKE YET (2023)

Still from Hiona Henare, THEY AIN’T WOKE YET (2023)

LK: So to go back to THEY AIN'T WOKE YET. How did actor Lawrence Makoare come to be part of an art installation?

HH: As an artist, you don't want to waste anything. When I went into shooting the Tuteremoana films and that process, working with Muaūpoko Tribal Authority and Sweetshop & Green Productions, I already had this crazy vision that I was going to shoot extra footage just in case I wanted to do something later, like a video art installation. So that was always on the cards anyway.

When I was filming, I was deliberately shooting extra stuff and getting my actors to do extra things so that I had the footage. Then I was approached for the CIRCUIT project, and I thought, "Yeah, I do have something actually, I do." And so I've used this footage to flex my video art installation muscles; the Tuteremoana films are [separate].

THEY AIN'T WOKE YET ties into the release of the Tuteremoana films and I guess I've been able to reimagine them, to jump into another dimension with those stories. We're still ticking the same boxes. I am Ngāi Tara. These stories, the Tuteremoana stories, are about my Ngāi Tara whakapapa. We're still in the same universe. And that's how Lawrence and Isis are included in this work.

Still from Hiona Henare, THEY AIN’T WOKE YET (2023)

LK: You are quite a prolific filmmaker and artist. Can you talk about your short film I Am Paradise that's having its world premiere at this year's Whānau Mārama: New Zealand International Film Festival?

HH: I Am Paradise was a really interesting project for me because it was one of those films that I could never have control of. It just had that badass mana wahine or bad mana wahine wairua about it. What I mean by that is, we shot it in 2018. It was ready for world release at the beginning of 2019 and it got shelved. For numerous reasons, nothing to do with me. But I think at the time, it felt like it was the right thing to do. And I always knew that it would happen when it happens.

I've really had my allies around me, people like film editor Annie Collins and the New Zealand Film Commission. And they've said to me, "Don't give up. Don't give up." And I haven't given up. I never gave up on it. I just knew, I just had this feeling that the film had to do what it's got to do. And I couldn't be more pleased with what we were able to achieve in a small amount of time on a really small budget.

What I've really learned, from my time with Apichatpong and doing the Tuteremoana films and I Am Paradise, and I think this is really true of all artists, is that when you've got a problem, you've got to solve it creatively. And when you don't have budget and you don't have time, you just make shit happen.

LK: Well, I think, Hiona, closing on that note, sometimes things are meant to happen when they're meant to happen. And I hope that I Am Paradise goes on great journeys around the world and that you get to go to all these places. And we really look forward to seeing your work on display at Masons Screen. It's obviously part of all the other creative things going on for you.

Thank you so much for this time from CIRCUIT! Mauri Ora!

Hiona Henare's THEY AIN'T WOKE YET (2023) is CIRCUIT’s fourth annual Matariki commission for Masons Screen in Pōneke, and runs from 18 July to 28 August 2023.