As I walk into Artspace Aotearoa on Karangahape Road in Tāmaki Makaurau Auckland, I feel prepared but disarmed. I am here for a solo show by the esteemed Indigenous filmmaker of the Abenaki Nation Alanis Obomsawin—To move between: Healing and Resistance—which features four of Obomsawin’s documentary moving image works and three related etchings. In anticipation, I have read about Obomsawin’s distinguished lifetime as an artist, activist, filmmaker, and educator. I have read how her work is about racism, and the injustices experienced by the First Nations people at the hands of the government of Canada. I know this now, which is why I feel a little bit prepared.

As an artist of Māori and Pākehā descent, with experience practising and teaching law, I am aware of similar legal scars in our own historical and cultural landscape in Aotearoa New Zealand. So I expect some discomfort—but I still want to see these works in the gallery, and to listen to and experience the stories Obomsawin wants to share with me.

Installation view, Alanis Obomsawin, To move between: Healing and Resistance, 2023. Image by Andreas Müller, courtesy of Artspace Aotearoa.

Installation view, Alanis Obomsawin, To move between: Healing and Resistance, 2023. Selected ephemera, vitrines. Courtesy the artist and the National Film Board of Canada. Image by Andreas Müller, courtesy of Artspace Aotearoa.

In September 1941, the New Zealand government used the Public Works Act 1928 to compulsorily acquire Tainui Āwhiro ancestral land for use as an emergency airfield during the Second World War. The land, known as Te Kōpua, was the hapū papakāinga (where the family homes were located). The conditions for the acquisition though, required the land to be returned if no longer needed for the original purpose.(1)

When it was no longer required as an emergency airfield, in 1969 the Raglan County Council, without consultation with local Māori, leased the land to the Raglan Golf Course, which developed it into a 9-hole course. This was enjoyed by locals, Māori and Pākehā, until the Raglan Golf Course expanded to become an 18-hole course. Among other things, this expansion included turning an urupa or sacred burial site into a sand bunker at the 18th hole. To make way for the final link, the burial site was completely bulldozed, the fences flattened, and the graves left unrecognisable.(2)

From this moment onwards, Tuaiwa Rickard, also known as Eva Rickard, began her campaign of protest and petition to the government to see the return of her iwi’s ancestral land. Her actions included fencing off the urupa or burial site to prevent golf players using it, and karakia to protest the desecration of this tapu or sacred site. In February 1978, in an attempt to lift the tapu of the area, local iwi and their supporters arrived to perform this ceremony and to protest during the club’s annual golf tournament. Before they were able to do this, the 17 members gathered, including Eva Rickard, were arrested by the police for trespassing on the Raglan Golf Course. After a further five years of court action and negotiations, Te Kōpua was finally returned to and vested in the Te Kōpua Trust. The airfield itself was not included in this settlement.(3)

Installation view, Alanis Obomsawin, To move between: Healing and Resistance, 2023. Image by Andreas Müller, courtesy of Artspace Aotearoa.

I hear ambient sounds of children laughing, leaves rustling, and I am sure there’s a croak from a frog. On a repeat visit I catch a faint but consistent beat of a drum. A woman’s voice guides me into the gallery, calming and insistent: Sigwan (2005). I scan the room, noting the four monitors and screens marking the perimeter of the gallery. By a long stretch, it reminds me of a courtroom. I am not sure which one I want to experience first. I know that each one will require a commitment, and probably another viewing. But I am getting charged up and it’s almost like I’m thinking, "Which fight do I want to wade into first?"

Installation view, Alanis Obomsawin, Sigwan (2005). Courtesy of the artist and National Film Board of Canada. Image by Andreas Müller, courtesy of Artspace Aotearoa.

On the 25th May 1978, a large contingent of New Zealand police officers and army personnel forcibly evicted and then arrested 222 peaceful protesters, and demolished buildings belonging to the Ōrākei Māori Action Committee at Takaparawhā (Bastion Point) in Tāmaki Makaurau Auckland. Refusing to leave their ancestral lands, the group occupied the land for 506 days. Ngāti whātua o Ōrakei’s protest was in opposition to the government’s decision not to return the land—as required under its compulsory acquisition—but instead announcing plans to develop a luxury housing development on the coastal headlands.

Earlier that year, the government had offered to return some of the land and buildings to Ngāti Whātua o Ōrakei on the condition that they paid $200,000 towards the development costs. Rejecting this ‘offer’, the non-violent protesters remained on the lands until their arrest and removal on day 507. Ten years later, the Waitangi Tribunal 1987 report recommended that the land in question be returned to Ngāti Whātua o Ōrakei and that they be paid $3 million to develop the land. The following year, the government agreed.(4)

Installation view, Alanis Obomsawin, Poundmaker’s Lodge: A Healing Place (1987). Courtesy of the artist and National Film Board of Canada. Image by Andreas Müller, courtesy of Artspace Aotearoa.

Two chairs face a single monitor on the floor for Poundmaker's Lodge: A Healing Place (1987), and I note it’s one of the shorter durations. Tempting. It looks a bit like a 'witness stand' and the gallery blurb describes "a documentary on an addiction treatment centre in St. Albert, Alberta for Indigenous people." But I will return to this one at another viewing, for the first work I am most drawn towards is Kanehsatake: 270 Years of Resistance (1993).

Behind a modest curtain, and in front of a row of chairs, the actions and evidence of the Oka Crisis or Kanehsatake Resistance fill the wall. For over an hour, I watch and listen to their stories of resistance and relentless urgency that lasted 78 days, and responded to a nine-hole expansion to an existing golf course on Kanien'kéhaka ancestral lands.(5) In protest, members of the Mohawk community, known as the Mohawk Warriors, erected barricades that denied access to the land in dispute. In response, local police, including a tactical intervention squad and riot police, brought in semi-automatic weapons and strategically positioned police cars to create their own blockades, with trained marksmen and other officers surrounding the Mohawk people inside the lines. The film documents tense standoffs between the two groups; armoured vehicles are challenged by Warriors on motorbikes, and long periods of restlessness feel ready to tip over into aggression and violence.

Installation view, Alanis Obomsawin, Kanehsatake: 270 Years of Resistance (1993). Courtesy the artist and the National Film Board of Canada. Image by Andreas Müller, courtesy of Artspace Aotearoa.

It was hard viewing; the experience was physical, and I was only just hitting half-way. But here were the material facts in visual form, front and centre. And Obomsawin’s skills behind the camera, 'in the moment', provide such a brave, raw (yet polished), and generous account of what happened. An account unlikely to ever be offered by the provincial and federal governments. Watching the rest of the film online, I learn more of Obomsawin’s bravery in the face of relentless fear, limited food and sleep, and also of her persistent determination to safely record, first-hand, what was happening to her people.(6) In an attempted raid on the protest camp, police deployed tear gas against the Mohawk, followed by an exchange of gunfire that resulted in the death of a police officer. As a standoff ensued, police blocked or limited Mohawk supporters from bringing in food and supplies to the enclave.(7) Eventually, the federal government committed to buying the land, therefore preventing the expansion from going ahead; the Mohawk blockades were bulldozed and the last remaining Warriors retreated.

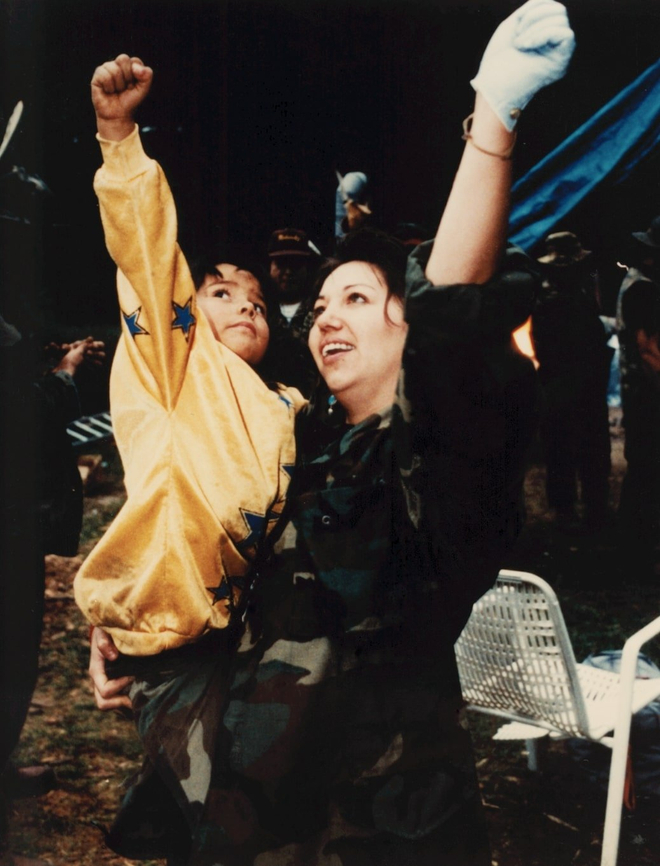

Kanehsatake: 270 Years of Resistance (1993). Directed by Alanis Obomsawin. Produced by Wolf Koenig and Alanis Obomsawin. Photo credit: John Kenney © 1993 National Film Board of Canada.

Kanehsatake: 270 Years of Resistance (1993). Directed by Alanis Obomsawin. Produced by Wolf Koenig and Alanis Obomsawin. Photo credit: Shaney Komulainen © 1990 Shaney Komulainen.

Activist and academic Dr Ranginui Walker (Te Whakatōhea) had this to say about Ngāti Whātua’s Joe Hawke, a prominent leader during the occupation at Takaparawhā (Bastion Point). "I think you have to be brave to put your body on the line in front of the State, the might of the State that can crush you like a beetle underfoot."(8)

Installation view, Alanis Obomsawin, Kanehsatake: 270 Years of Resistance (1993). Courtesy the artist and the National Film Board of Canada. Image by Andreas Müller, courtesy of Artspace Aotearoa.

Perhaps the film I resonated with most was We Can't Make the Same Mistake Twice (2016), a mammoth effort tracing a nine-year legal battle between the Assembly of First Nations and Family Caring Society of Canada against the federal government of Canada, for the systemic discrimination and significant lack of funding and care provided by the federal government to First Nations children and their families on reserves. "Their case against Canada is a stark reminder of the disparities that persist in First Nations communities and the urgent need for justice to be served."(9)

As a former practising lawyer and now a teacher of law, and in particular legal reasoning and 'how to interpret a statute', the courtroom arguments were familiar. I saw the resilience in the elegant testimony from survivors and caseworkers, up against the unceasing attempts by government lawyers to avoid liability—to diminish, belittle, and patronise the advocates for the First Nations children and their families—enabled by the mechanisms of the court. Towards the end of the video, we hear the poignant testimony of a survivor of the residential school system. In particular, we hear about the day his mother escorted him into an unfamiliar three-storey building, handed him over to strangers who spoke another language, and left without an explanation or goodbye. This was the beginning of several years of torment and abuse for him and other children at the school, and the separation from and breakdown of the only family he had.

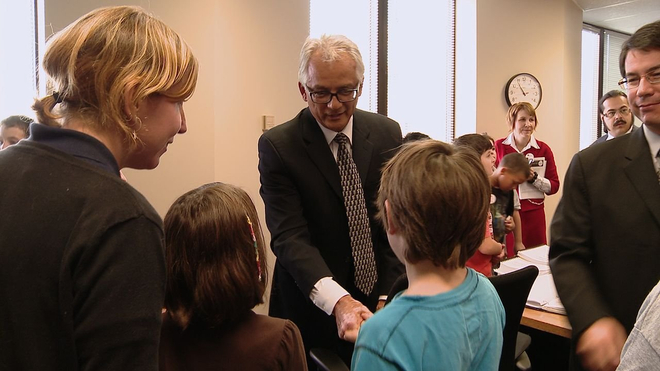

Alanis Obomsawin, We Can't Make the Same Mistake Twice (2016), film still. Courtesy of the artist and the National Film Board of Canada.

Alanis Obomsawin, We Can't Make the Same Mistake Twice (2016), film still. Courtesy of the artist and the National Film Board of Canada.

This film is a challenging work of art and a significant legal exhibit. To see this court case recorded and presented in a gallery setting was like watching a legal drama on TV; everyone spoke well and without pause, interruption or lengthy delay. In this work, Obomsawin has provided her people and Indigenous people all over the world with ways to retell stories from an Indigenous perspective, one that challenges the very institutions that have discriminated against generations of First Nations children. She has listened and now asks us to do the same.

Alanis Obomsawin, We Can't Make the Same Mistake Twice (2016), film still. Courtesy of the artist and the National Film Board of Canada.

Ihumātao is an archaeological site of historic importance in the suburb of Māngere, Auckland. Once a pā site, it stands on the Ihumātao Peninsula, at the base of Ōtuataua, part of the Auckland volcanic field. The land in this area was historically confiscated from local Māori by the New Zealand government as ‘punishment’ for supporting the Kingitanga movement and resistance against the British Crown. It was then sold to the Wallace family who farmed it for 150 years.(10)

In 2016, the construction management company Fletcher Building acquired the site from Auckland Council as part of a planned housing development project. Opposing the proposed development, members of SOUL (Save Our Unique landscape), led by spokesperson Pania Newton (Ngāpuhi, Te Rarawa, Waikato, Ngāti Mahuta), occupied the site, staging wānanga and protests from 2016 through to 2020. For five years, the protesters and occupiers claimed they were protecting the site. Members of the public joined their protests, the Māori King also made a visit and lead talks on behalf of local iwi with government officials in an attempt to reach a resolution. At the end of 2020, the government agreed to purchase the land back from Fletcher Building and a Memorandum of Understanding was entered into between the Kingitanga, the Crown, and Auckland Council for a sustainable future for Ihumātao.(11)

Alanis Obomsawin, We Can't Make the Same Mistake Twice (2016), film still. Courtesy of the artist and the National Film Board of Canada.

Alanis Obomsawin, We Can't Make the Same Mistake Twice (2016), film still. Courtesy of the artist and the National Film Board of Canada.

The government’s closing arguments presented in We Can't Make the Same Mistake Twice attempt to drive home once more their claim that they have made no mistake, that the government has not discriminated against First Nations children and their families on reserves. But they were wrong. It is gratifying to learn the outcome and to know this legal record will exist for generations to come: some will celebrate, others will cringe. The challenge is still there though, to make sure it doesn’t happen again.

I leave the gallery feeling a bit lighter, jubilant perhaps. I realise the victory is legal, but in some cases, it is a necessary engagement if we are to move between the tension of resistance to the act of healing.

I don’t know if Indigenous intergenerational trauma can be healed. I cried while watching and listening to Kanehsatake: 270 Years of Resistance, as I did upon witnessing similar historical injustices in Bastion Point—The Untold Story, the 1999 New Zealand on Screen television production directed by Bruce Morrison.(12) That film triggered a sadness in me that was hard to shake in front of Alanis Obomsawin’s brave and generous documentary and visual artworks. But Obomsawin’s own challenge demands that we engage in a deeper listening to and therefore awareness (and perhaps understanding) of the social, cultural, legal, and political differences in our lives. A listening that may be uncomfortable, but a listening that is not simply about waiting for that moment when someone agrees with you.

To move between: Healing and Resistance was on view at Artspace Aotearoa from 2 September to 4 November 2023. Alanis Obomsawin is a member of the Abenaki Nation, one of Canada’s most distinguished filmmakers, and a leader of the Indigenous struggle.

Layne Waerea (Ngāti Wāhiao, Ngāti Kahungunu, Pākehā) is an Auckland based artist whose practice involves carrying out performance art interventions that question and challenge preferred social and legal behaviours in the public sphere.