Toloa Tales, an exhibition of two new video works by Edith Amituanai and Sione Tuívailala Monū at Pātaka in Porirua, Te Whanganui-a-Tara, is an exploration of belonging and the diasporic situationship with 'home'.(1) Though discrete works, the two artists’ films gently intertwine, and overlay their individual narratives on top of the same coral-hued skies of Sāmoa. As an Aotearoa-born Tongan whose family has expanded across oceans to California, Tāmaki Mākaurau, Gadigal—the usual Pasifika haunts—I am constantly considering questions such as, where do I really belong? What is 'home'? That’s why diasporic stories are my favourite. I find comfort in their relatability, holding space for my feelings of insecurity and cultural pride while also showing me different ways of being, and reminding me of the vastness that comes with being tangata Pasifika. And the two films in Toloa Tales have it all—inter-spatial travel, hot glue guns, so many sunsets, and (chosen) family.

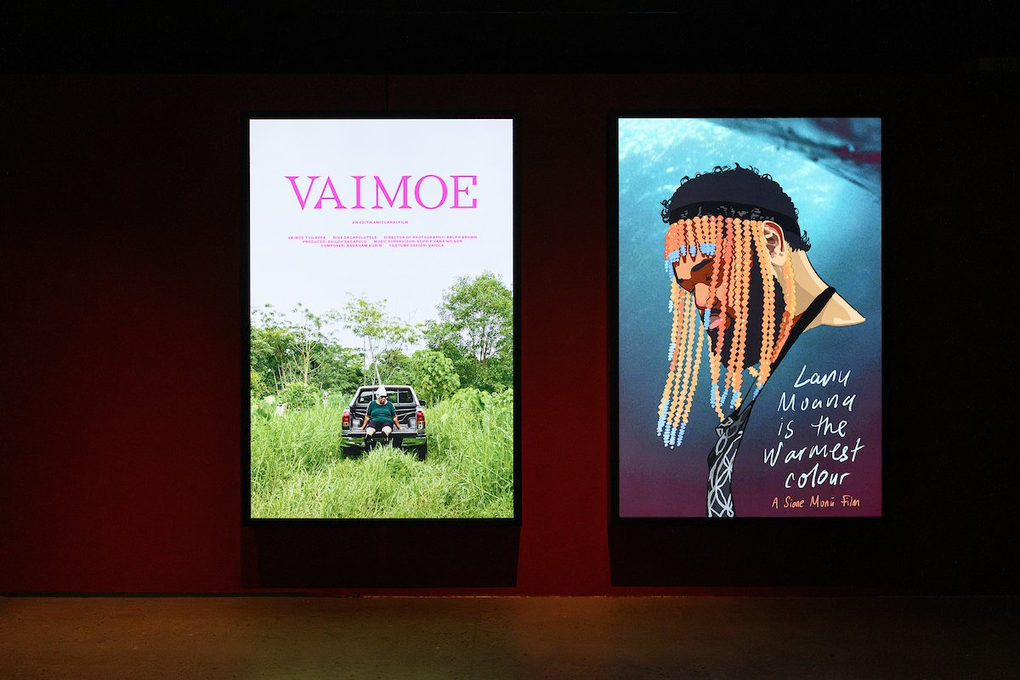

Installation view, Edith Amituanai and Sione Tuívailala Monū, Toloa Tales, Pātaka Art + Museum, Te Whanganui-a-Tara Wellington, 2025. Photo by Mark Tantrum.

The title of the exhibition riffs off the Sāmoan proverb, "e lele le toloa ae ma’au lava ile vai," which means the Pacific duck or toloa flies far, but will always return to water—that no matter how far one journeys, there is always a desire to come home. A beautiful metaphor for the diasporic spirit. Toloa Tales speaks to the complexities of being far from home whilst always longing for it, and the ways in which we might rebuild home wherever we land.

Walking into the exhibition space, you are greeted with the wonder that is Vaimoe Tuilaepa, Edith Amituanai’s aunty, recently returned to Sāmoa after several decades living in the United States. Vaimoe is that aunty. Stacks of gold rings snapping open a crayfish tail, a sei behind her ear to work in the taro plantation, an updo and white kitten heels for Sunday mass. In Amituanai’s film of the same name, Vaimoe narrates her own story to us in gagana Sāmoa. She begins with her upbringing in a koko plantation in Sāmoa, her move to Hawai’i as a young woman, the joys and tragedies of her life in Alaska, and finally her decision to come back home. Tuilaepa’s retelling of her past is viewed against the backdrop of her life today in Sāmoa. It is a simple life; living off the land, spending time with family over food, and going to church. We see shots of her amongst nature, surrounded by the deep green of the taro, or floating atop the shimmering ocean in her va’a in search of sea cucumbers, accompanied by the strum of a steel guitar.

Edith Amituanai, Vaimoe (2024). Single-channel HD video, 16 min. Image courtesy of the artist.

Amituanai knows how to capture a person's essence with simplicity and care. I think this is due to her ability to offer the subjects of her works a sense of comfort, giving them the confidence to exist in front of the camera with naturalness and a fullness of self. This quality defines her photographic practice, and also carries Vaimoe. The film is layered visually and thematically, as Amituanai utilises imagery to emphasise the emotional beats of Tuilaepa’s story. Old photographs and newspaper clippings are layered on screen, as if Tuilaepa was there with you, placing each artefact one on top of the other as she tells her story.

My favourite moment in the work is when Tuilaepa sings a pese. It’s evening, and we find her sitting in inky darkness, an ‘ie lavalava around her waist, legs dangling off the edge of the fale. The artificial light from inside hits her back, and a bluish glow illuminates her face. She sings into the night:

Samoana (Samoana)

Ala mai (Ala mai)

Fai ai nei (Fai ai nei)

Le fa’afetai (Le fa’afetai)

I le pule, ua mau ai

O lou nu’u, i le vasa

People of Samoa

Arise (wake up)

Give (now)

Your thanksgiving

To the Most High, who gave you

Your country, here in the ocean

The song is called 'Lo ta nu’u' ('My dear country'). It is a celebration of Sāmoa, and calls on its people to be proud of their land and what they have inherited. The scene is expertly placed within the film’s narrative, offering up a moment of reflection for the audience to digest the heartbreak and grief that Tuilaepa has shared with us. Learning the meaning of this pese after seeing the film made me love this moment even more. Something I had viewed as a moment of prayer, a moment that acknowledged Tuilaepa’s grief for her son, was now also a melancholic rendition of a song about cultural pride. With this scene, Amituanai skillfully stretches the complexity of Tuilaepa’s story.

Edith Amituanai, Vaimoe (2024). Single-channel HD video, 16 min. Image courtesy of the artist.

After a difficult period of living abroad that left her feeling lost, and with the encouragement of her sister, Amituanai’s mum, Tuilaepa was able to return home to Sāmoa. Vaimoe feels like a new beginning in the place that she was always meant to be. She describes her life in Sāmoa as a "re-do," and there is something really special about seeing someone live multiple lives. It is a reminder that there will always be time and space to navigate things, to follow the wrong star, catch a crosswind, and still land somewhere to take rest.

Sione Tuívailala Monū, Lanu Moana is the Warmest Colour (2024). Single-channel HD video, 27 min 31 sec. Image courtesy of the artist.

A score of rhythmic strings grounds frenetic iPhone footage—shot out the window of an Auckland Transport bus—in the cinematic universe of Sione Tuívailala Monū’s Lanu Moana is the Warmest Colour (2024). The title, a nod to the sapphic coming-of-age film directed by Abdellatif Kechiche, replaces the sexual awakening of a French teenager in a small-town with the leitī rite of passage—portal travel. Once in every leitī’s lifetime, the power that they hold manifests as a portal. No one knows when their portal will appear to them, or where the portal will take them. For Monū, their portal arrived at the age of 25 to transport them from their home in Onehunga to the Islands of Sāmoa. Lanu Moana is the Warmest Colour is made up of a series of vignettes that capture Monū’s portal adventure, in which we see them in Sāmoa, working behind the scenes on Edith’s film shoot, helping a friend prepare for the Miss Samoa Fa’afafine pageant, and getting advice from and spending time with their MVPFAFF+ family.

If you follow Monū on Instagram, you will know their stories give followers a fantastical glimpse into their everyday life, embellished with expertly picked musical accompaniments and a quick-witted humour that is tapped into digital culture. These online videos are a key part of Monū’s artistic practice. Looking back at an Instagram highlight from November 2023, titled '🇼🇸 pt 1' and documenting the creation of the films in Toloa Tales, one story bears the text, "So my new art piece: imagine my stories but shot in 4K 😂."(2) And they’re not wrong. Lanu Moana is the Warmest Colour is definitely the progeny of Monū’s Instagram-based practice, but I don’t think they give themselves enough credit. While the work is beautifully shot in 4K, it is also expansive and reflexive in ways that lean into the time and space of its longer format.

Sione Tuívailala Monū, Lanu Moana is the Warmest Colour (2024). Single-channel HD video, 27 min 31 sec. Image courtesy of the artist.

In the work, Monū layers handwritten text and animation over their moving images, weaving in their practice of adornment and nimamea'a tuikakala (Tongan fine art of flower designing). This adornment is used thoughtfully throughout the film; figures get pulled out of the narrative vignettes into surreal portraits, become adorned with floral masks that are emblazoned with Sāmoan place names—vibrant, beaded, and sparkling. Monū’s floral work and beaded headdresses organise the visual narrative but also signify a world where leitī and fa’afafine live freely. We meet others that have been crowned with these beaded adornments. They give Monū advice via portal message from Onehunga, diligently hot glue shards of iridescent CDs to a pageant gown, and show Monū around their family’s fale tele. On the one hand, these are people just living, but Monū’s adornment is also a subtle reminder that this is a leitī universe, a world seen through a queer Pasifika lens. In snippets of intermittent off-screen dialogue, Monū talks about art-making and the realities of needing to produce a work to meet the exhibition’s deliverables. This dialogue positions the making of the film, and our reality as a viewer of the work, in opposition to the world that the film itself creates. Lanu Moana is the Warmest Colour is a manifesto for how the world should be, a place where MVPFAFF+ are free to live and exist, with time to think, make, and create.

So much of Lanu Moana is the Warmest Colour is made up of moments between friends. There are many vapes shared, warm beers on sticky nights, and soft conversations. The scenes with Sione and Edith sharing a Taula beer and a cigarette are the best. One moment is composed, perhaps accidentally, like a Gauguin painting. Edith is sitting on the concrete floor of a fale, legs outstretched, with Sione lying on their stomach facing her as they talanoa. Illuminated by the bright white fluorescent lights above, their bodies glow amidst the tranquil darkness of the Sāmoan night. Vape smoke fills the air as they reflect on why the portal brought Sione to Sāmoa. What is the meaning of it all? Sione remarks that maybe it was to learn more about filmmaking from Edith. It is such a gentle exchange but expresses a depth and warmth that was surprisingly touching. Speaking to the power of collaboration, this friendship is at the heart of the exhibition.

Edith Amituanai, Vaimoe (2024). Single-channel HD video, 16 min. Image courtesy of the artist.

Sione Tuívailala Monū, Lanu Moana is the Warmest Colour (2024). Single-channel HD video, 27 min 31 sec. Image courtesy of the artist.

The alchemy of Toloa Tales is this magic. Separately, each of the works is an intimate story, a glimpse into the world of its subject, told with a clear artistic voice. Viewing them together, the perspective shifts. These are not two separate stories but rather two versions of the same. One glorious trip to Sāmoa, two distinct outcomes. Vaimoe is a portrait of a woman who has lived a full life across oceans and has returned home for a "re-do," finding her place at home once again. Lanu Moana is the Warmest Colour is a portrait of a leitī whose life is still becoming, and in being transported to Sāmoa finds connection and learning, and the opportunity to imagine a world they may not be able to access on the other side of the portal. This shared reality unfurls over the course of the exhibition. Vaimoe sets the scene, establishing its own world. In one scene, Tuilaepa takes a video on her phone, as a performer spins a nifo oti (fire knife). In Lanu Moana is the Warmest Colour, this clips is deconstructed and transformed: again we see Tuilaepa watching the nifo oti, but this time with Monū beside her, with a handy recorder and headphones, capturing the scene’s audio. This doubling of perspective speaks to the layered and complex nature of belonging that is explored in each work, and also in the way the two artists share the exhibition space. Two screens are positioned back-to-back, facing out to different ends of the space. Each film plays simultaneously on a loop; while watching one you see the light of the other bouncing off the walls behind, and overlapping sounds bleed into each other at quiet moments. But this is a dance, not a competition. Each works together to share the space, one never overpowering the other. The two artists exist in symbiosis, a mutualism. They are better together.

Ultimately, Toloa Tales embodies the vastness of diasporic identity as two narratives coexist and diverge. Amituanai and Monū’s films serve as a poignant reminder that ideas and beliefs about one's identity and belonging are ever-evolving, shaped by where we are, where we've been, and where we choose to go.

Toloa Tales was on view at Pātaka in Te Whanganui-a-Tara Wellington from 29 March to 6 July 2025.

Gloriana Meyers (Tongan, Pākehā) is a creative from Te Whanganui-a-Tara. With a background in Art History, she has worked across the sector in museums and galleries, guided by her passion for contemporary Moana arts.

.jpg)