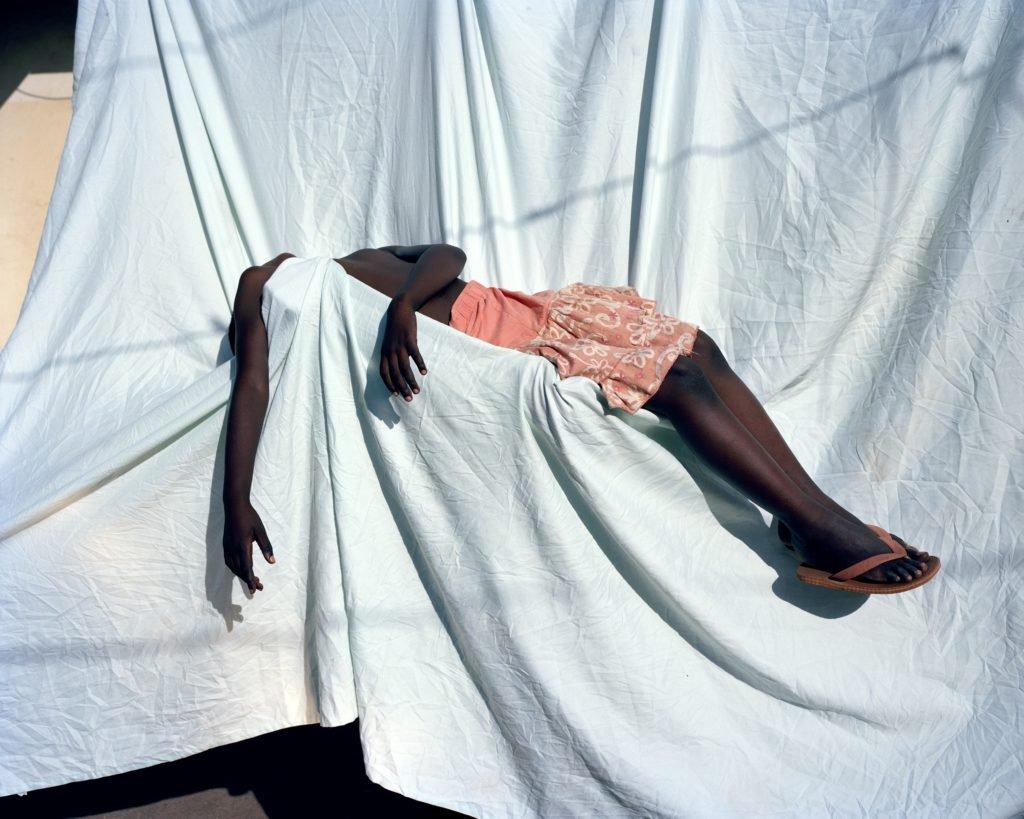

White people and their gaze! White people looking at black people, making them pose; white people making black people into mere bodies and objects for their aesthetic enjoyment. Is that what is going on with Viviane Sassen: Lexicon? Sassen’s photographs, taken in some indeterminate part of Africa, show black subjects in various often obscure poses, apparently at times directed by the photographer herself. Faces are often obscured. There is the occasional suggestion of bondage (especially in Ayuel (2010)); there is a more than occasional suggestion of lifelessness in the limp or prone bodies. Indeed, body bags, open graves and gravestones extend the argument about lifelessness further, with images that evoke, if they don’t explicitly show, the death of the body.

Here is one way to look at the photographs, then: as not just another bad case of colonial gaze, but a critique of it, the photographer’s eye making the connection between its own power to make images and the power to reduce subjects to slaves, to bodies, and by extension to corpses. Lexicon seems, at a second glance, to be exactly this: gaze that critiques gaze, hoping perhaps to work with the ambiguity and with the viewer’s combination of complicity and discomfort.

So, is it critical or colonial? Our impulse might be to draw up a kind of balance sheet. Does it count against her that Sassen is also a fashion photographer? Her somewhat fetishistic focus on the beauty of black skin might not help her much either—wasn’t skin colour supposed to be an irrelevance, a distraction, in our colourblind humanist anti-racism? It might, on the other hand, help that her early childhood was spent in Kenya? The critical point might also be driven home by the supporting works. Pieter Hugo’s music video, for a cover of Joy Division’s She’s Lost Control by South African rapper Spoek Mathambo, occupies the south end of the space; while Alain Resnais and Chris Marker’s film Statues Also Die is at the north. Marker and Resnais’s film, especially, offers an unambiguous attack on colonialism and the complicity in it of ethnographic categorisation, collection and display—an argument that, of course, also targets photography; while Hugo’s video is explicit in its images of, among other things, (post-)colonial violence.

Installation view of Control (2011) Pieter Hugo. Photo by Shaun Waugh, Viviane Sassen Lexicon at City Gallery Wellington, 2014

There is another way to see the exhibition, however, one that allows the supporting works to reflect differently back on the photographs. This is to see Lexicon as the latest of a number of curatorially-driven juxtapositions of different media held in Wellington in recent months. I am thinking, in particular, of its predecessor at the City, South of No North, an MCA touring exhibition that combined the photography of Laurence Aberhart and William Eggleston with painting by Noel McKenna; and, of course, of the Adam Gallery’s current Cinema and Painting. To see Lexicon in this context is to think about how those juxtapositions make arguments about medium and subject matter—whether, as in Cinema and Painting, we focus on media, making distinctions between them even as we also trouble them; or whether, as in South of No North, the differences between media are relatively obscured in the face of an argument about the images’ content (as when we moved from a McKenna domestic interior to an Aberhart one, say).

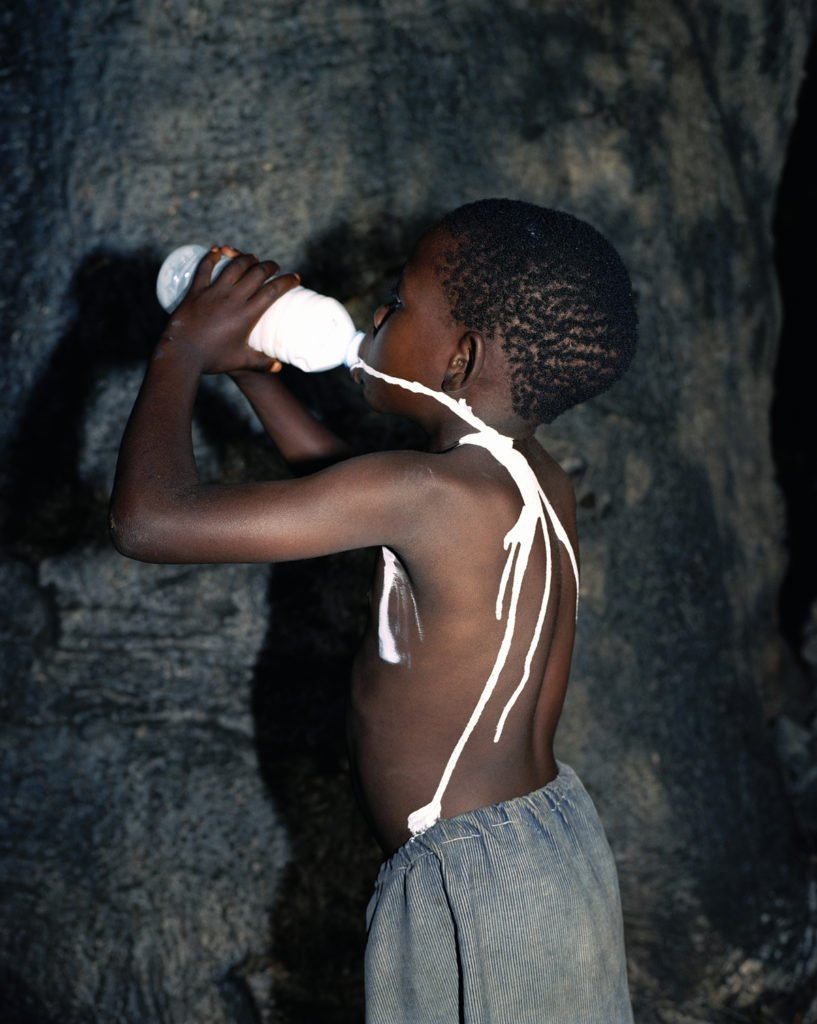

How, then, does medium in Lexicon—the decision to juxtapose photography with moving image works—inform its subject matter: race, Africa? There are startling continuities between the media, to be sure, as when we see the same white stuff, milk, apparently, or glue or paint, spilling over a boy’s dark skin in Sassen’s Milk (2006) spilling again, in exactly the same way, in Hugo’s video. In a similar vein, Sassen’s graves, her faces, her dusty ground more generally, also seem to crop up again in the video. The rhyme of images from photos to video and back is one of the exhibitions most surprising pleasures, and one that seems to mean that content trumps medium.

Still from Milk (2006) Viviane Sassen. Courtesy Stevenson, Cape Town and Johannesburg

However, the pastiche and animation that are a necessary part of a music video also contrast highly with the photography’s stillness. The moving image works incorporate their images into narrative and argument—whether the polemic and grand narrative of Statues Also Die, or the postmodern allusions and associations of Hugo’s video. Returning from the moving image works back to the photographs, we have an opportunity to be struck again, in contrast, by the enigma they present, their refusal to explain themselves, their refusal of narrative. The pictures’ uncertainty, seen as an aspect specific to the photographic medium, is not now one of interpretation (colonial vs. critical) but concerns the fact that they hold themselves back from all interpretation.

Sassen’s "naive" interest in skin colour seems, in this light, less like a colonist’s fetish, and more a result of the indifference of the camera to its subject matter. It is in contrast to the work of the moving images that the photographic subject can seem most stubbornly like what it is, torn from any political or narrative context. It is here too that the less directorial, more "found" photographs come into their own—it is these works that emphasise photographic indifference, that emphasise that the camera might stumble equally on anything, framing it in apparently arbitrary ways. In some of these photos, such as Shadow (2004) or Spring of the Nile (2006), skin is in shadow to the extent that it is difficult to distinguish one from the other—black is nothing but the absence of light on the photosensitive surface. In part, this might lead in the direction of a somewhat surprising aesthetic, even art-historical, realisation: the suggestion that chiaroscuro, which relies on the lighter object’s emergence forward from a dark field, is a technique for white people—for black skin, it can as easily fail. In other images such as Solomon’s Knot (2010) or Crimson and Carmine (2010), body dissolves into pattern, and skin becomes surface. The reduction of skin to mere colour and mere surface relates, of course, to the lifelessness, the mere bodies and dead bodies, to white people’s uses. It also, however, allows a more positive, even egalitarian view: the generosity of photography, one that allows skin to just be skin.