I have struggled to write about this exhibition for weeks. My first response was eviscerating grief for each of the three discrete artworks by Miranda Bellamy and Amanda Fauteux that comprise Radicant: the ultimate deterritorialisation of plant and fungi fragments rotating in filmic cryogenic space (also titled Radicant, 2024), the hermetic existence of convolvulus sealed in glass cylinders (Pavilion, 2025), and a tall staff of unprovenanced kahikatea, burned and carved (Signal, Echo, 2024).(1) The questions I asked myself involved the usual interrogative words: why, what, and how? Why would anyone do this to living plant beings? (convolvulus, perhaps kahikatea)? What purpose does it serve? And, somewhat repetitively, how could this be allowed to happen?

So, grief, yes, and bewilderment. My well-intentioned aim was/is to write reparatively, particularly with regard to plant life. This means I write about the life force or sentience of all living beings, noting aesthetic or biological instances in which this life force is revered and encouraged to flourish. I wanted (and still want) to write about reparative artworks, literature, poetry, and regenerating ecosystems because I want to counter devastation with the possibility and potential of healing. But I could not write about Radicant from this place of good intentions, and this presented an ethical challenge.

It is evident that my grief and bewilderment were a response to the exhibition, yes, but it is also easy to trace their source in the violence of my ethical apparatus: I wanted to write reparatively, and I could not; I wanted to shoehorn the creative output of others into my supposedly ethical-aesthetic apparatus, and I could not. This is a form of violence.

I gave up the apparatus. Now I had to confront my complicity: that by describing the artworks, and trying to find answers to the interrogative words, I would participate in the rippling out of violence.

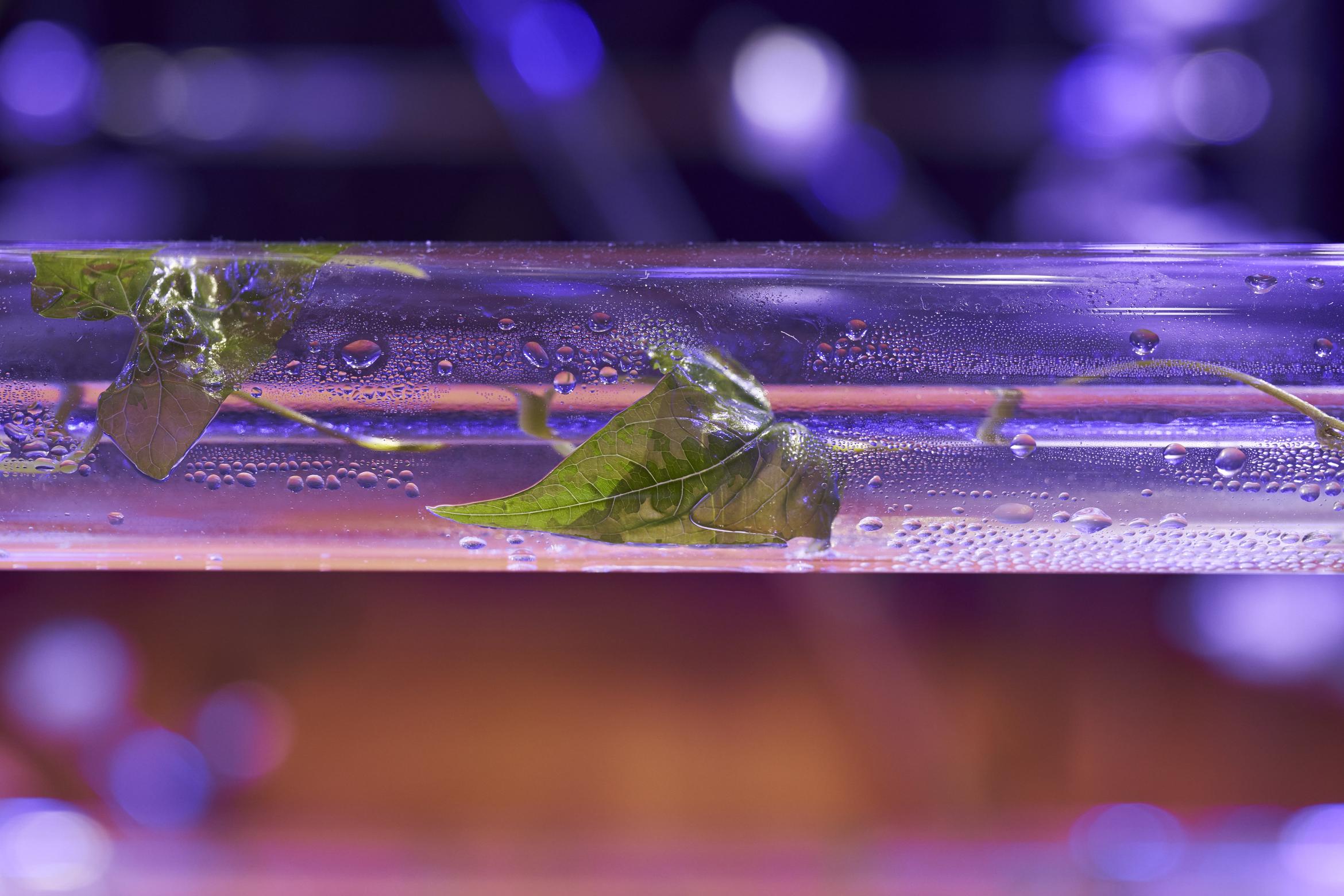

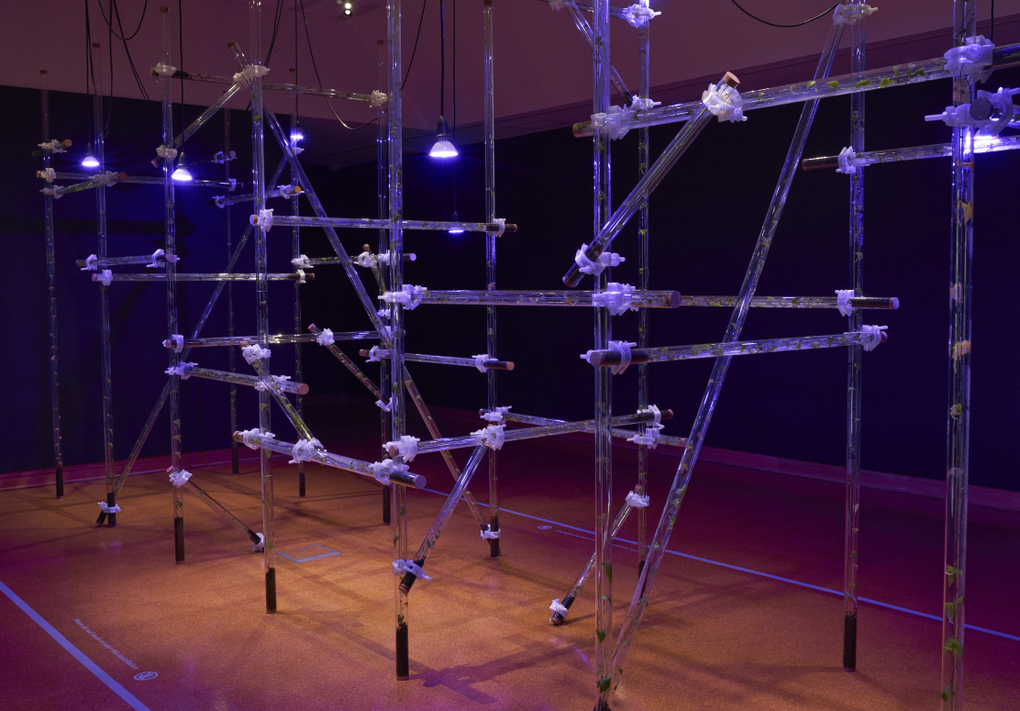

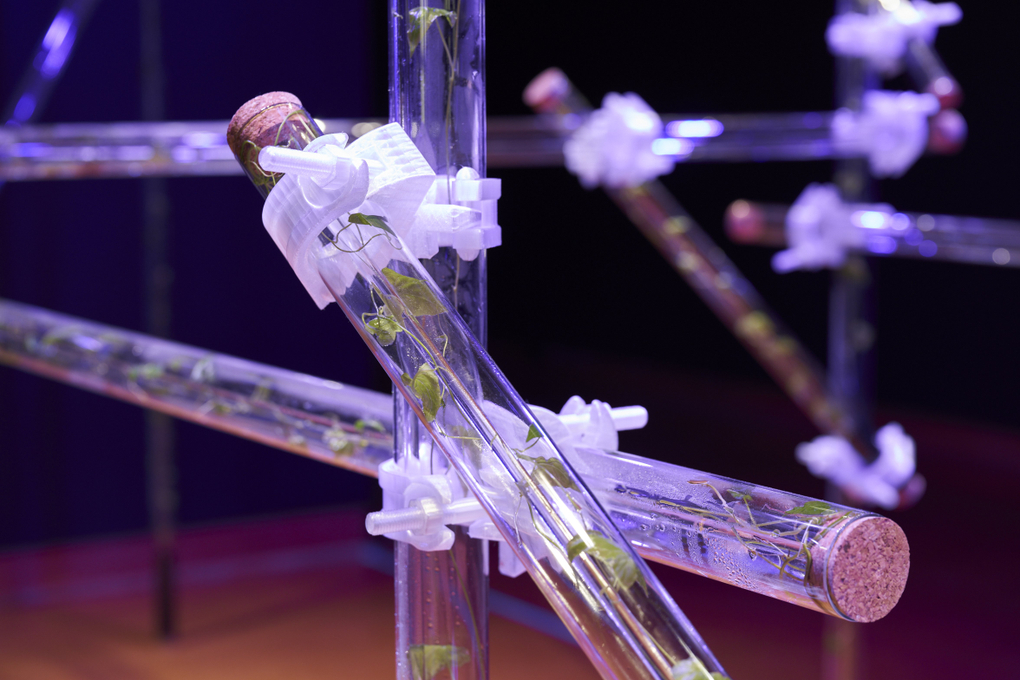

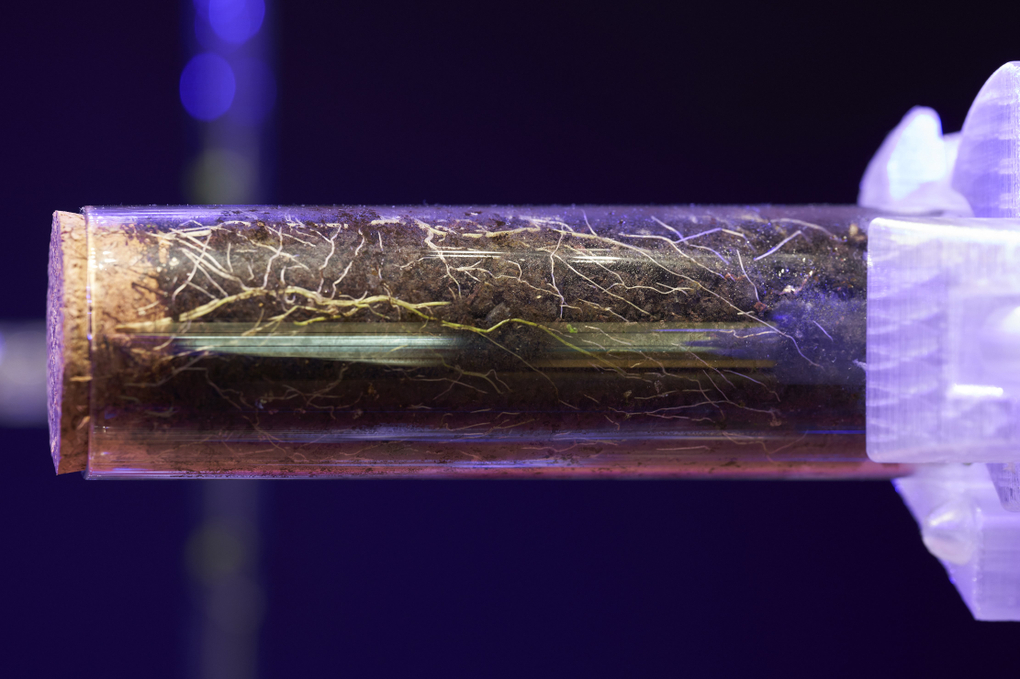

Miranda Bellamy and Amanda Fauteux, Pavilion (2025). Installation view, Radicant, Hocken Gallery, Ōtepoti Dunedin, 2025. Image courtesy of Hocken Collections Te Uare Taoka o Hākena.

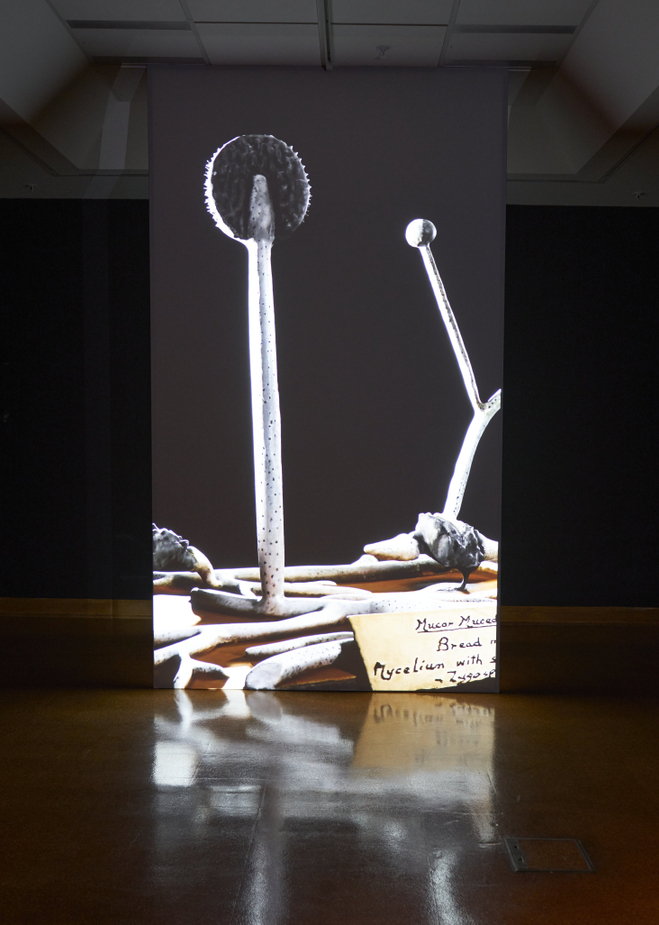

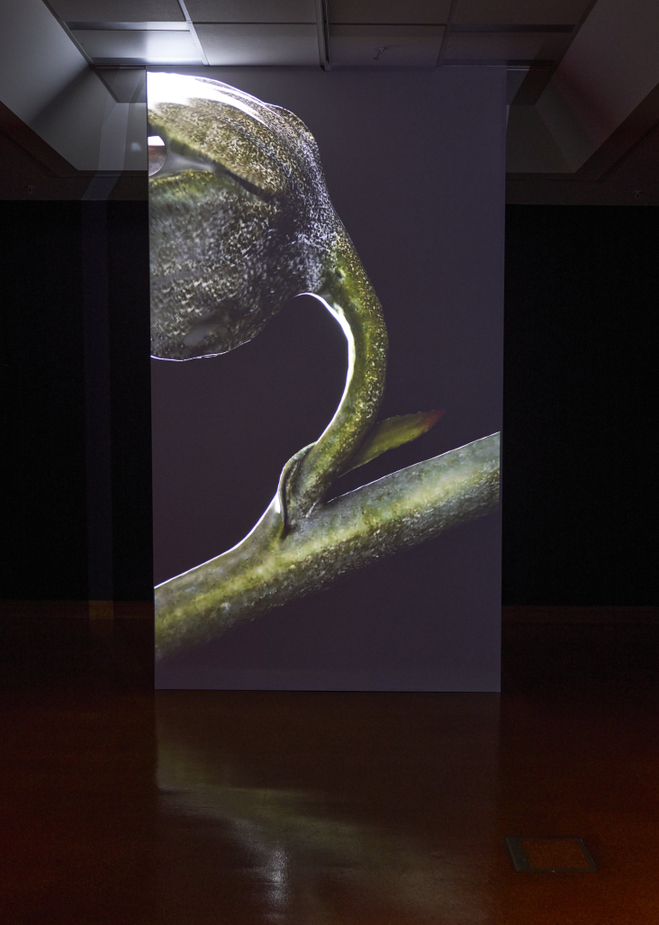

According to the support and guidance materials (an exhibition card, texts in the catalogue that accompanies Radicant), the starting point for the large plant and fungi fragments that rotate as if in deep space was a set of late nineteenth-century botanical models made from "papier-mâché, glass beads, gelatin, and feathers … by the Brendel Company in Berlin … [that] were purchased by the University of Otago as vital teaching aids."(2) Before we move beyond this starting point, it is interesting to note that these models were manufactured from plant beings themselves: the papier-mâché that was once trees, the glass from silica and limestone, the gelatin quite possibly from animals at this stage of history, and the feathers presumably from birds.

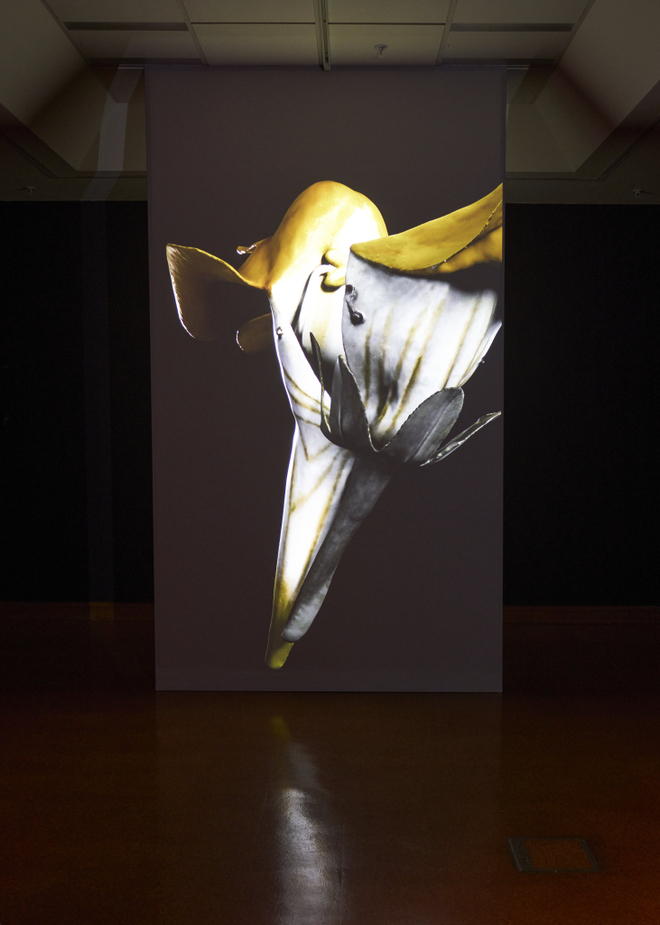

Miranda Bellamy and Amanda Fauteux, Radicant (2024). Installation view, Radicant, Hocken Gallery, Ōtepoti Dunedin, 2025. Image courtesy of Hocken Collections Te Uare Taoka o Hākena.

Though these old teaching models take plants and fungi away from their living source, they are still materially tethered to their origins in fairly distinguishable ways. To update the models for the contemporary world—perhaps as a mode of archival institutional critique—artists Bellamy and Fauteux (who jointly shared the 2024 Frances Hodgkins Fellowship) used 3D scanning technology to facilitate their digitisation, manipulation, and filming with CAD software, and created ancillary digital models of plants and fungi that appear together in Radicant (2024), the 4K video work. While we know that vast areas of forests in countries like Brazil are being cut down to house data servers and reservoirs of water diverted to cool them, in order to meet AI and data capacities, the digital persists (is persisted) in appearing somehow less polluting and destructive.(3)

So even if an attenuated materiality remains in the transposition from tangible model to digital model, is this really a critique? I know, I’ve been holding out on you—is the perpetuated archive really only a subset or a practice of colonisation, of empire? Let’s investigate this work in greater detail.

The background is deep-space black. There is no oxygen; no living being—aside from microscopic stardust—could survive. The orientation is vertical; this is a phone-view of deep space. Or perhaps it is an altar. Over 19 minutes, 13 plant and fungal beings enter from one or more planes and typically leave from a different plane. Who are they? In their common names (in the order I came upon them):

~ yellow water lily ~ waterwheel plant ~ stinking chamomile ~ purple loosestrife ~ cultivated pea ~ filamentous fungus ~ Venus flytrap ~ toadflax ~ Scots pine ~ foxglove ~ liverwort ~ field horsetail ~ pinmould ~ (4)

Miranda Bellamy and Amanda Fauteux, Radicant (2024). Installation view, Radicant, Hocken Gallery, Ōtepoti Dunedin, 2025. Image courtesy of Hocken Collections Te Uare Taoka o Hākena.

No claim for this work’s country or regional specificity is made in the supporting materials—and perhaps accurately so, for the bioinvasion (planned or happenstance) of First People homelands was vast, encompassing the Americas and Oceania amongst other continents and archipelagos. The artists’ biographical statement acknowledges Fauteux’s hometown of Mi’kma’ki (Sackville, New Brunswick, Canada) in addition to Bellamy’s Ōtepoti (Dunedin, New Zealand). If Radicant (the work) targets bioinvasions in Canada and Aotearoa, this is not made explicit. If this work is a critique of colonisation, it does not cleave to the two aforementioned lands. If this critique exists, it does so as a generalisation of colonialist appetites.

The question guiding this text is whether the violence towards plant and fungal beings in this exhibition is intentional; is Radicant a heat-seeking critique of the archive and of bioinvasive colonisation? Attendant questions would ask if violence is a useful means of critiquing violence—which the archive and colonisation most definitively are. Bifurcating down another path is an equally troubling question: if neither the archive nor bioinvasive colonisation are coherent or convincing as rationale, why is violence being directed towards plant and fungi?

Let’s return to the plant and fungal beings shorn of apparent materiality who rotate endlessly in anaerobic deep space. Are these the least loved, the most invasive, hated, virulent, or unworthy? What is the rationale for their collation? Is it merely the Brendel models? Or do these beings individually and as a collective choke native plants and waterways, and interfere with the well-being of native soils, insects, and animals? How are these once-beings 'radicant'?

Miranda Bellamy and Amanda Fauteux, Radicant (2024). Installation view, Radicant, Hocken Gallery, Ōtepoti Dunedin, 2025. Image courtesy of Hocken Collections Te Uare Taoka o Hākena.

'Radicant' is an important word in this exhibition. It is its title, the title of the video work, and the title of a collection of thirteen poems by Colleen Coco Collins included in the exhibition catalogue, which is also titled Radicant. What does it mean? Radicant is a botanical term that describes a plant who grows from the node of a prostrate stem.(5) Think ivy and convolvulus, who are prostrate (lying) on the ground and grow from a node. I am not a botanist, but of the thirteen plants and fungi featured in the sequence of poetry and video, it is readily apparent that not all of them are radicants. This may or may not matter, but if the term is intended as a means of botanical categorisation, its deployment in this sense is inaccurate.

To take three of the group—pods of peas grow from individual peas, a Scots pine grows from seeds released from the pinecone, and there is a volunteer foxglove in my backyard that clearly grows from seeds that are currently stored in the fox’s glove (flowerhead) awaiting dispersal by wind, birds, or me. If not all the selected plants and fungi are radicants, do they instead share properties of outrageous prolificacy? Is their presence egregious by default? Without geographic specificity, we can’t answer this question with any certainty.

Miranda Bellamy and Amanda Fauteux, Radicant (2024). Installation view, Radicant, Hocken Gallery, Ōtepoti Dunedin, 2025. Image courtesy of Hocken Collections Te Uare Taoka o Hākena.

What does the poet say? Amidst dense references to Greek and Roman myths, in Collins’ poems, there are many emotions at play. The poet variously implores ("Give onto me the treacle of death"), worships ("I genuflect and set my ears to the stalks"), and reveres ("I’m parched and my love/ bounds unslaked and gloved through the tall through the dark/ through the trees").(6)There are expressions that could be described as reparative—in the sense of honouring all beings, even if these particular examples happen to still be relatively loved: stinking chamomile, cultivated pea, and foxglove, respectively. Where some or all of these plant and fungi beings are unloved, the poet remediates, offers grace, raises up.

Collins' voice reading her poems scores the soundtrack to Radicant the video, yet however earthbound and warm, she cannot ameliorate the eviscerated plant and fungi fragments that are hoved into view by unseen algorithmic pincers. These spectres are bled of life, appearing as transparent ivory, gilded an acid green, turned an unpalatable verdigris. "The spectral unrest of the dead," they are advanced towards the viewer and shown from vantages that our eyes could not naturally track.(7) These beings are objects for algorithms to scan, rotate, swivel, and turn upside down as if gravity did not exist. In the case of the foxglove, the unseen camera traverses her form as she roils in space before entering the flower’s open glove/head, trekking over her speckled petals until there are none.

In his book The Radicant, Nicolas Bourriaud makes a distinction between (artist) radicants, "which develop their roots as they advance" and (artist) radicals, "whose development is determined by their being anchored in a particular soil."(8) Artist radicants do not stress their roots, their origin, their homeland; they are nomadic, and merge with their host. Writing in 2009, Bourriaud was still captivated by the globalised nomad whose wandering could be normalised as the condition of their omitted or unexamined privileged mobility. While a Bourriaudan theorisation of the radicant is not explicitly operating in Bellamy and Fauteux’s work, it is interesting to note, in the intervening 16 years, how alien Bourriaud’s radicant sounds, and how, particularly for Indigenous peoples, the radical would be esteemed.

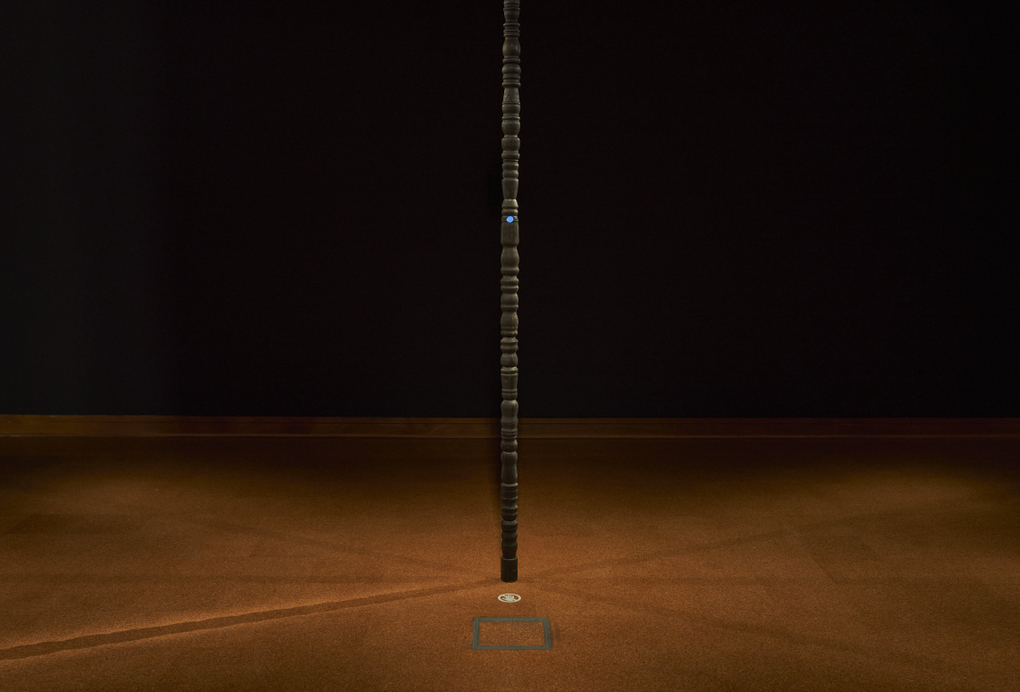

Miranda Bellamy and Amanda Fauteux, Signal, Echo (2024). Installation view, Radicant, Hocken Gallery, Ōtepoti Dunedin, 2025. Image courtesy of Hocken Collections Te Uare Taoka o Hākena.

This is an awkward segue, but the work I feel least equipped to write about is the most troubling. Signal, Echo (2024) consists of the aforementioned burned and carved kahikatea staff. Embedded in the cork floor, the staff reaches from floor to ceiling and houses, at its midpoint, a small screen viewed through a circular hole in the wood. The subject of the small video work appears to be blue atmospheric fog, which would correspond with the 8-channel audio of land-based fog horns. According to the support material:

Each speaker represents a point on a compass rose, with the compositions geo-locating the origin and movement of plants across oceans to the shores of Te Kawau Tumaro o Toi Kawau Island, where Bellamy and Fauteux later encountered their dropped leaves, flowers, seeds, and fruit.(9)

It is clear that this work is complex, nuanced, and that it deals explicitly with the archival and bioinvasive colonialist themes raised above. But it is a work that is most successfully appreciated via this written description; a condition that is exacerbated by the presence of the staff, which approaches an oversize tokotoko or orator’s stick in likeness. From where and how was the kahikatea taken? Someone better positioned than me might be able to explain (or refuse to explain) the feeling that there is a breach of some kind. This is the closest I can come to explaining how dangerous it felt to be in that room. I chose to enter and peer at the little blue circle of fog, but I did not feel comfortable.

Miranda Bellamy and Amanda Fauteux, Signal, Echo (2024). Installation view, Radicant, Hocken Gallery, Ōtepoti Dunedin, 2025. Image courtesy of Hocken Collections Te Uare Taoka o Hākena.

Of all the three works, Pavilion (2025) embodies most clearly the oft-titled Radicant. It is also the most palpably violent and cruel. Here, the viewer can see somewhat-alive convolvulus existing in glass cylinders that are prostrate (horizontal), vertical, and diagonal. From the entubed, radicant, stem-and-leaf bodies, interconnecting structures that resemble scaffolding have been constructed. Is there a relationship between convolvulus and building sites, convolvulus and urban gentrification? Why are living beings contained in glass and made to resemble scaffolding, or the backdrop to an offbeat rave, with ultra-violet lights helping the plants to grow?

Miranda Bellamy and Amanda Fauteux, Pavilion (2025). Installation view, Radicant, Hocken Gallery, Ōtepoti Dunedin, 2025. Image courtesy of Hocken Collections Te Uare Taoka o Hākena.

Miranda Bellamy and Amanda Fauteux, Pavilion (2025). Installation view, Radicant, Hocken Gallery, Ōtepoti Dunedin, 2025. Image courtesy of Hocken Collections Te Uare Taoka o Hākena.

Is this one of the many points where we dig deep again and seek to scry archival or bioinvasive colonialist rationale?

For the archival, we have plant and fungi models (video), we have containment though the subject is alive (convolvulus), and we have archival recordings of fog horns (staff).

For the bioinvasive colonialist, we have a host of generalised plant and fungi that include thirteen floating fragments (video), convolvulus, and fascinatingly, geo-located introduced plants on Kawau Island that are not named (staff). To counter the omitted specificity of Signal, Echo, there is an unprovenanced native tree who has been burned, carved, and had inserted inside them a foggy video work.

What does this prompt us to think or do? Do we exclude living beings from all exhibitions? Do we go out and plant lots of native trees? Do we nurture convolvulus, or do we destroy it? Did we need the violence of this exhibition to consider or provoke these thoughts?

Perhaps I will try out a reparative lens here at land’s end, to note (but never exonerate) that the western 'we' lives with a collective psyche of eviction and severance from the garden and the rest of nature. It is a wound that has been inflicted on invaded and globalised cultures. It is with this wound and unbelonging that so many of us live and make with. Collectively then, the western we learns or remembers that thoughts and actions directed towards any living being affect all living beings; we must therefore take care with all thoughts and all actions lest we cause suffering to any and all sentient beings.

Radicant was on view at the Hocken Gallery, University of Otago, from 15 February to 26 April 2025. The exhibition continues at Ilam Campus Gallery, University of Canterbury, from 28 May to 18 June 2025.

Robyn Maree Pickens lives and writes in Ōtepoti Dunedin. She is the Ursula Bethell Writer in Residence at Te Whare Wānanga o Waitaha University of Canterbury from July 2025 to January 2026.