On the way to the Rotterdam Film Festival I sit at London City Airport with two British-based film programmers. Like almost everyone else in London they are devastated by the recent UK election, which returned the Conservative party to power and confirmed Brexit as a done deal. One is listening to a podcast on the life of George Orwell, as if to imagine a radical future through a radical past. She mentions a recent magazine headline: "Why can't the Left get its act together?" Then they share a knowing joke about "going off to watch some films in Rotterdam."

Even for those of us based on the other side of the world, Brexit, Trump, etc has been hard to ignore. And in such times of political crisis it’s not uncommon to question one’s faith in art. Faced with the politics on its’ doorstep, how did Rotterdam 2020 respond to this moment of global democratic shift? What did artists from Aotearoa and the South Pacific bring to the conversation? And how did Rotterdam make space for wary individuals, antagonists and malcontents?

CIRCUIT was invited to participate in six events at IFF Rotterdam, which took place as always in the deep mid-winter chill of the European January. Four films by Tanu Gago, Natasha Matila-Smith, Atong Atem and Janine Randerson were selected to screen in various programmes which either celebrated new talent, new perspectives or sought to affirm a global community for artists film. Tanu Gago and myself also took part in two public talks.

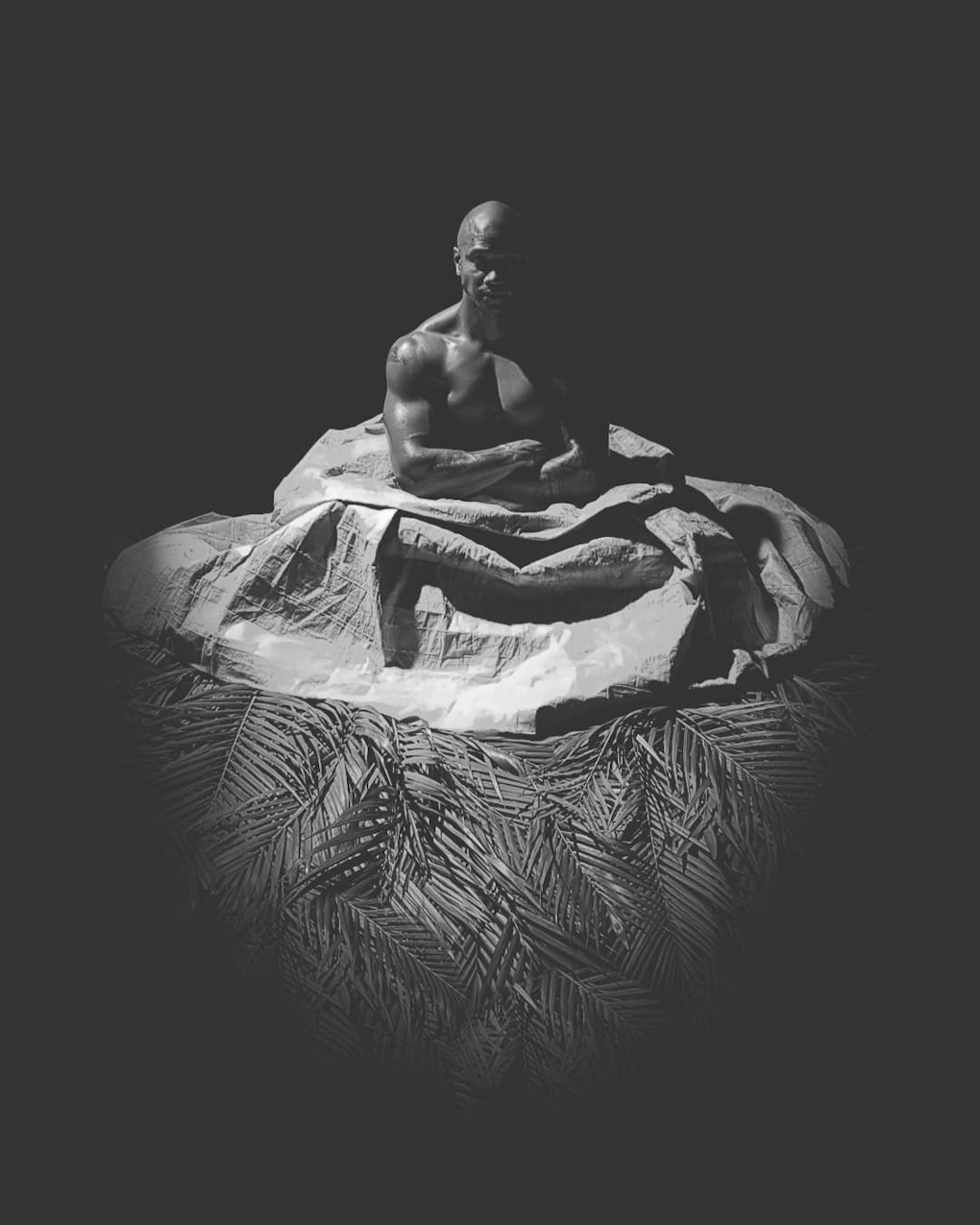

Still from Apparatus (2018) Tanu Gago

Tanu Gago’s Apparatus (2018) screened in Bodily Rituals, a programme curated by IFFR young curator Darunee Terdtoontaveedej, which sought to “… imagine the limitless possibilities of queer existence” through films by non-Western filmmakers. At a follow-up talk entitled Sacred Beings Tanu joined two fellow film-makers onstage. While "supportive of the cause", some admitted mixed feelings:

“It’s always somewhat of a trap to be in a programme like this… In the end there is a ghettoisation of the subject…“—Wang Shui

“…every culture, every country, every gender terminology has its own context and struggles … it’s more complicated than what we naively think is just a universal context.”—Sarnt Utamachote

While agreeing that a group programme does not always reveal the nuances of individual situations, Tanu nevertheless extracted a shared signal;

“…I do feel connected to the films you presented in the programme and …one thing they articulated consistently was an alternative position to colonization and also the impacts of what that looks like”—Tanu Gago

45 minutes into a polite but measured conversation a commotion starts from the back of the room. A voice exclaims, “I pour water for my children and what do I forget? To drink water myself! It is time for me to live my life with full inspiration and full aspiration…!” Making their way to the stage the speaker begins a series of breathless exercises, cues the song Maniac (1983) from the musical Flashdance (1983) on their iPod and crawls over the panelist’s water table, prompting a hasty intervention to stop glasses crashing to the floor. Is this someone’s psychic meltdown? Is it a performance? Everyone in the room seems genuinely baffled.

It is, in fact, Becoming Another, a performance by Dutch-based artist Raomi Muzho Saleh. The intervention completely shuts the book on the panel, but it also addresses slow-percolating frustrations expressed earlier in the conversation to the effect of: "Why are we explaining these things to straight audiences again?" "How does a film festival format serve the film, the subject, the community?" Raomi’s answer is effectively to deliver on its own terms and leave us to just deal with it.

Audience camera: Becoming Another, a performance by Raomi Muzho Saleh at Sacred Beings - On Gendering, IFF Rotterdam 2020. Panel (l to r) Sarnt Utamachote, Tanu Gago, Sarafine van Ast, Wang Shui

"Deal with it" is also part of the artistic strategy of American spoken word artist, musician and performer Lydia Lunch, the subject of Beth B's documentary The War is Never Over (2019). Chronicling Lunch’s artistic production since the late 1970s, the film affirms Lunch as a clear-sighted performer who has fully registered her own trauma, clocked the “the holy trinity of patriarchal bullshit” spread through family, church and state, and chosen to respond by “turning the knife out, not in”. After the screening Lunch is a defiant individualist—“You know 72 fuckin’ minutes about me. You think you fuckin’ know me? You don’t even know yourself!” Nevertheless she affirms the wider context of her work ”.... mine is not the worst fuckin’ story, I just have the loudest voice …hoping I am screaming out for others.”

-and-Beth-B-(right)-at-IFFRotterdam-2020.png)

Lydia Lunch (left) and Beth B (right) at IFFRotterdam 2020

Elsewhere, at KINO 4, Natasha Matila-Smith’s If I die, please delete my Soundcloud (2019) was CIRCUIT’s contribution to Guilty Pleasures, a compilation of 15 works nominated by members of DINAMO, a network of international video art distributors who meet at the festival. Matila-Smith’s work is a late night series of on-screen texts describing inner thoughts which dance on the edge of self-pity without ever quite falling in. It's also funny, and strikes a chord with the audience, many of whom tell me how much they enjoyed it as an alternative to the predominantly white, privileged and European "sad girl" phenomenon. The next day, a second DINAMO screening entitled (No) Dialogue is also sold out. Here CIRCUIT’s nomination is Janine Randerson’s Waiho, Retreat (2017). The soaring peaks of Ka Roimata o Hinehukatere (Franz Josef Glacier) look stunning on the big screen, but the quiet mapping of the retreating ice by on-screen performer Tru Paraha signals an ecological disaster in motion. Once again, Tanu Gago’s words in the Sacred Beings panel provide a useful summary of the efficacy of film in a global context:

There’s a language of film and cinema which is arbitrary to gender, culture and identity …I love that you can that create a piece of culture …that openly rejects the English language and still presents an idea to people.

Waiho, Retreat (2017) Janine Randerson

Shivering in a 4 degree chill, Rotterdam Film Festival is spread across multiple venues. Across the Erasmus Bridge at the cinematheque Lantaren Venster, Dr. May Adadol Ingawanij (familiar to many in Aotearoa from her visit to the 2016 CIRCUIT Symposium) interviews four members of Australia’s Karrabing Film Collective, "an indigenous media group based in Australia’s Northern Territories that uses filmmaking and installation as a form of grassroots resistance and self-organisation." Karrabing’s films are urgent fast-cut montages, using dramatic recreations, documentary and rap to describe the daily threat of social services (“hide your kids”), wrecked infrastructure and the ongoing legacy of colonisation. Comprised of somewhere between 30 to 80 members the group also counts in its membership American anthropologist, activist and gender studies professor Beth Povinelli, who edits the films and clearly plays a vital role as a bridge between the group and institutions like Rotterdam. One of the Karrabing members is a teenager who bravely sits on stage alongside his mother, brother and Beth. Though nerves seem to limit his participation and his cap remains jammed down hard over his eyes, his presence is a powerful statement from the group on inter-generational solidarity.

May Adadol Ingawanij in conversation with the Karrabing Film Collective, IFFRotterdam 2020

Solidarity! Just before leaving NZ I’m asked to chair a panel entitled Collaborative Constellations. I say yes. The panel is a group conversation with no less than five representatives of three collectives in the fields of distribution, exhibition and lab production. In Rotterdam, the panel looms through my jetlag. I struggle to think of a convincing through line to bring everyone together. Flicking through the news channel in my hotel room, the UK is about to turn it's back on the collective project and exit the European Union. Is it too absurd to say that the festivals' rationale for this panel might be a response to Brexit? Whether this is true or not, the panel resolves to simple questions of collective practice—"Why come together? What issue were you trying to address? How do you make decisions?" I enjoy panelist Bernardo Zanotta’s idea of collectively applying for funding and splitting it up amongst the individual projects of the members in his film production collective. I forget to ask "What happens if the group decides it doesn’t like one of the members ideas?" Some panelists advocate for the integration of artist production and exhibition facilities under one roof as a means to shore up tenuous economies and gather audiences. From the floor Greek film programmer Vassily Bourikas says this is a mistake that leads to insularity.

Speaking of which, as I depart Rotterdam it is three days until Brexit, an event that will sever Britain from a 47-year pact established to promote common goals of peace, trade and exchange in Europe, and which some have described as “an epic act of self-harm.” In the ensuing airport stopovers en route to NZ I download every Brexit podcast, article and live update, with a side dish of the Trump impeachment, and an occasional detour into Viz magazine to reconnect with the true heart of British culture. At the last meeting of the European Parliament to feature British involvement, I hear how Nigel Farage and his fellow Brexiteers wave UK flags as a childish send-off to their former colleagues. Meanwhile the American Republicans vote against calling witnesses. At a trial.

What does the future hold in the wake of these shattering of communal institutions and assumed norms of governance and responsibility? Nobody knows. But at least in the world of film, and its community of makers, Rotterdam 2020 sought to assert that difference and commonality can indeed exist in the same space. Thanks to the festival for inviting us to be part of the conversation.

Thanks to Peter Van Hoof, Theus Zwakhals, Erika Balsom, Helen de Witt