Ki te kotahi te kākaho ka whati, ki te kāpuia, e kore e whati.

If a reed stands alone, it can be broken; if it is in a group, it cannot.

The iwi advance as a group, en masse, bearing sacred stones, kohūta mauri, to place in the Gallery foyer. For them, urban alienation is yesterday's news. Out of cracks in the ground grows a new harvest, to bring all together. And together they are enfolded, not in the noise of information but in silent contemplation of kaupapa Māori: a Māori way of doing things, Māori metaphor. Belonging is ancestral connection, genealogy, whakapapa. It is the same tribal waka, but with different paddlers.

Dunedin Public Art Gallery currently hosts three exhibitions that derive from a te ao Māori—a Māori world view—approach to curation. Hurahia Ana Kā Whetu: Unveiling the Stars and Paemanu: Tauraka Toi — A Landing Place have been put together by senior artists in the Paemanu Kāi Tahu visual arts trust collective, while the boutique exhibition He Reka Te Kūmara (How Sweet the Kūmara) has been assembled by four young Māori women curators, using a number of the same artists. The result is a network of associations as intricate as a string game (whai) across the three exhibitions to form essentially one epic and epochal mahi toi responding to mana whenua: the prestige of the land. In this cultural display Pākeha are the Other, the manuhiri, the guests, the visitors.

Installation view of Paemanu: Tauraka Toi – A Landing Place [Tohorā] (2021) at Dunedin Public Art Gallery. Photo by Justin Spiers.

left: Tūtakitaka (2021) Madison Kelly and Mya Morrison-Middleton / centre: Taki Apakura (lament) (2021) Ephraim Russell / right: Untitled (rendered) (2021) Martin Awa Clarke Langdon

Located smack dab in the middle of a colonial settlement, built on what was once Māori tribal land, the Dunedin Public Art Gallery as an institution has finally acknowledged the significance of its location by turning over nearly all of its exhibition space to art crafted on indigenous concepts—on matauraka Māori, the Māori knowledge framework. As part of this acknowledgement of local iwi, the language of the signage around the shows incorporates Kāi Tahu dialect in preference to standardised Māori's Ngāi Tahu terminology.

'Paemanu' or 'bird perch' is a name taken from an artwork by Kāi Tahu artist Ross Hemera, which in turn derives from ancient Māori rock shelter art in North Otago depicting an ancestor figure with two outstretched wings and a row of little birds perched on each wing.

An oneric mural in red and black charcoal and pencil by Hemera stretches along entranceway walls and, reworking rock shelter art motifs, elegantly serves to connect all three exhibitions as if in one dreamtime. Hemera grew up at Omarama and was inspired in his childhood by the runic drawings on the whitestone cliffs along the Ahuriri River, with their powerful sense of ritual. They remain his touchstone as an artist.

Hurahia Ana Whetu: Unveiling the Stars is the result of a 2019 invitation from the Gallery to Paenamu to 'elevate Māori art history within the context of the Gallery's permanent collection' in a spirit of collaboration. And so the hand-me-down cultural cringe of the salon, the metropolis, the international art fair, has been sidelined by a kaupapa Māori intervention intended to energise and uplift.

Installation view of Untitled (1991) Peter Robinson, in Hurahia ana kā Whetū at Dunedin Public Art Gallery (2022). Photo: Justin Spiers

Artworks selected range from Michael Parekowhai's The Bosom of Abraham (1999), a radiant sequence of marae kowhaiwhai patterns placed along a corridor as plugged-in light fixtures, to Kāi Tahu artist Jacqueline Fraser's Ko Aoraki Te Maunga (1991), a quirky, interior-decorator wire-basket arrangement of the nation's tallest mountain, to Kāi Tahu artist Peter Robinson's Untitled (1994), a roadside produce-stall shed covered in a barrage of advertising slogans, and empty inside apart from the sign 'Sorry, sold out'.

The crowded hang of 'stars' includes artworks by all the Māori and Pasifika artists in the DPAG collection. Once token, they have become anchor points for revisiting the politics of identity. Colonial-era art, too, is revisited, with paintings by William Mathew Hodgkins and Petrus van der Velden and sculpture by Margaret Butler amongst those joining the kapa haka. Unveiling the Stars provides a new way to navigate, by-passing the twentieth-century faux, the po-mo, the exhausted or tired tropes of late Modernism for immediacy and a felt authenticity.

At least that is the intention, but there's also a sense that these vaulted and storied artworks refuse to be corralled so neatly to meet a canon-busting agenda. Period art of the past, given a jolt and galvanised into eye-rolling, hand-fluttering, tongue-poking stylistics, underpinned by an ever-changing rhetoric of enthusiastic Post-it-note-type poems and rhapsodic comments in guise of wall labels creates a turbulent emotional undertow that obscures rather than clarifies.

He Reka Te Kūmara provides another way in to Kāi Tahu naratives, literally, with black-painted, glass, push-doors inscribed with a te reo text in the copperplate handwriting of nineteenth-century Kāi Tahu rangatira Hori Kerei Taiaroa, who campaigned unceasingly for Crown recognition of Kāi Tahu land rights. This exhibition in a side-gallery under low-light, with its wall-painted invocations to Te Kore (the Void) and Te Po (the Darkness) feels womb-like, a wraparound caul where profane Pākehā reo seems almost an affront. On the walls are several female figure drawings by Ralph Hotere, and two large monotype prints of a new-born baby by Marilynn Webb that invoke Papatūānuku: the Earth Mother.

Also emerging through the subterranean gloom, gently illumined, are sculptural maquettes, shelf models, by Matt Pine and Shone Rapira-Davies depicting a symbolic marae archway and a creation myth respectively. But dominating the space is a large video screen featuring a looped short video work Kowhai (2017) by Aydriannah Tuiali'i. In it, the artist chants a melodious waiata while performing rhythmic hand gestures. She is dressed in yellow; her diminutive image is a set of kaleidoscope patterns across a black background. The performer appears to split in two and weave and reweave the positions of her arms. Her chant, a lullaby just under a minute and a half long, endlessly repeats, the tone pure. The effect is haunting and hypnotic, adding to the impression that one is in a cave in the realm of Hine-nui-te-po.

...the hand-me-down cultural cringe of the salon, the metropolis, the international art fair, has been sidelined by a kaupapa Māori intervention intended to energise and uplift.

Main entrance of Paemanu: Tauraka Toi – A Landing Place (2021), Dunedin Public Art Gallery. Photo: Justin Spiers

Upstairs in the sprawling Paemanu: Tauraka Toi—A Landing Place, all the 48 artists exhibiting have Kāi Tahu whakapapa—or contributed under Kāi Tahu guidance. Before Dunedin was established as a town, the tangata whenua, Ōtākou Kāi Tahu, landed their canoes on the shoreline at the Toitu Tauraka Waka, now reclaimed land along Princes Street, to embark on food foraging expeditions and later to trade with early settlers before gradually being excluded from the new settlement. This early history of interaction and subsequent marginalisation underlies the narrative of Tauraka Toi—A Landing Place, as does Māoritanga's holistic relationship with the environment, especially pertinent in an era where it is argued that indigenous thinking can help heal the planet.

Jennifer Katarina Rendall's video work Te Kōmāmā (2021) honours the energy and beauty of a clean, healthy river, deep in the mountains of Te Wai Pounamu. Water gushes, eddies, tumbles and sparkles over boulders and rocks, and this cataract of river-talk does indeed seem the mauri (life-force) embodied.

Ko te wai he wai ora (2021), Rachael Rakena (Kāi Tahu, Ngā Puhi). Film still. 16 channel film. Collaborating creatives: Paulette Tamati-Elliffe (Kāi Te Pahi, Kāi Te Ruahikihiki (Ōtākou), Te Ātiawa, Ngāti Mutunga) and whanau, Komene Cassidy (Ngāpuhi, Ngāi Takoto), Rachael Rakena (Kāi Tahu, Ngā Puhi), Michael Bridgman (Tonga, Ngāti Pākehā), Laughton Kora (Ngāi Tūhoe, Ngāti Pūkeko, Ngāti Awa), Iain Frengley (Ngāti Pākehā), Ross Hemera (Waitaha, Ngāti Māmoe, Ngāi Tahu) , Mara TK (Ngāi Tahu, Ngāti Kahungunu, Tainui), Amber Bridgman (Kāi Tahu, Kāti Mamoe, Waitaha, Rabuvai), and He Waka Kōtuia.

Out on the Big Wall of the mezzanine, a panoramic videowork lasting just under half an hour stretches across 16 large video screens. Ko te wai he wai ora (2021) has been put together by a group of 10, under the artistic direction of Rachael Rakena, to lament the degradation and pollution of traditional waterways and wetlands. First, an immense riverscape is seen from above, a flat pattern, the sluggishly moving body of water is serpentine like a taniwha. It shimmers across the palisade of screens, which here and there is surmounted by a design of curving lines like the snapped-off stems of the koru spiral. The electronic soundtrack is sombre, mournful. Beyond the willow trees of this river in trouble are farms, with the implication of farm run-off. Here, the wetlands have been transformed and cancelled by industrial-scale dairying.

The second part of the video starts by sliding like a sunbeam down into dark water from which a cloud of tiny bubbles rises. Abruptly the soundtrack transforms into the music for a vigorous kapa haka, and the water is made kinetic with underwater beings, looming and gesticulating, their legs in motion and their hands pushing against the wai (water). Their faces are so expressive they might be swimming for their lives, lungs bursting. These submerged performers are traditionally costumed amid swirls of red cloth. They represent defiant spirits of place: dramatic, admonitory, operatic. This is a powerful protest work, a kind of political megaphone announcing the environment is out of balance.

Installation view of Paemanu: Tauraka Toi – A Landing Place [Waka Tūpuna] (2021), Dunedin Public Art Gallery. Photo by Justin Spiers.

left: Becoming Sound (2021) Lonnie Hutchinson / right: Still Life with Albatross feathers, Pounamu and Coral Hearts (Ripiro Beach) (2014) Fiona Pardington

Lonnie Hutchinson's sculpture, Becoming Sound (2021) also offers a kind of megaphone, more literal as a giant silver and black metal cone-form that's horizontal on a mirror surface. The cone is patterned out of kawakawa leaves, which have themselves been turned into a pattern, as if perforated by kawakawa looper moths. This work might be read as being about kawakawa as a medicinal herb, a heal-all. The leaves are a traditional purifier of water, and also a soothing balm for injuries and pains. The cone floats as a mysterious sieve or net on the silvery surface, as if atop a water-well. The megaphone shape symbolises a call for unity, for group action.

Altogether, 'Paemanu: Tauraka Toi — A Landing Place', a long time in the making is about the aura, dignity, presence, and confidence of the Kāi Tahu iwi, hapū, whānau.

Whāia Tīramarama — The Search (2021) Rachel Ruckstuhl-Mann

Rachel Ruckstuhl-Mann's installation Kei Hea te Tuna? (2021) symbolically explores the foreshore around Ōtepoti with sculpture, performance, and film, in search of eels as evidence of a healthy ecology. The video work part of this installation Whāia Tīramarama — The Search is shamanistic and spell-casting, if also gloomy and at times murky. The artist, wearing a surrealistic costume of latex rubber gloves blown up like balloons—or moonlit jellyfish bladders—moves along underneath superimposed filmed layers of drains, culverts, and creek flows. This cinematic montage, made up of flashes and glimpses, is phantasmal, shadowy, nocturnal. The artist appears as a sequence of undulating organic shapes slithering in a eurythmic-type dance. Esoteric, inward, smeary, the video work, with its slow quest along dubious waterways, seems at once overly earnest and melodramatically poignant, an impression reinforced by its soundscape, available within the installation on headphones.

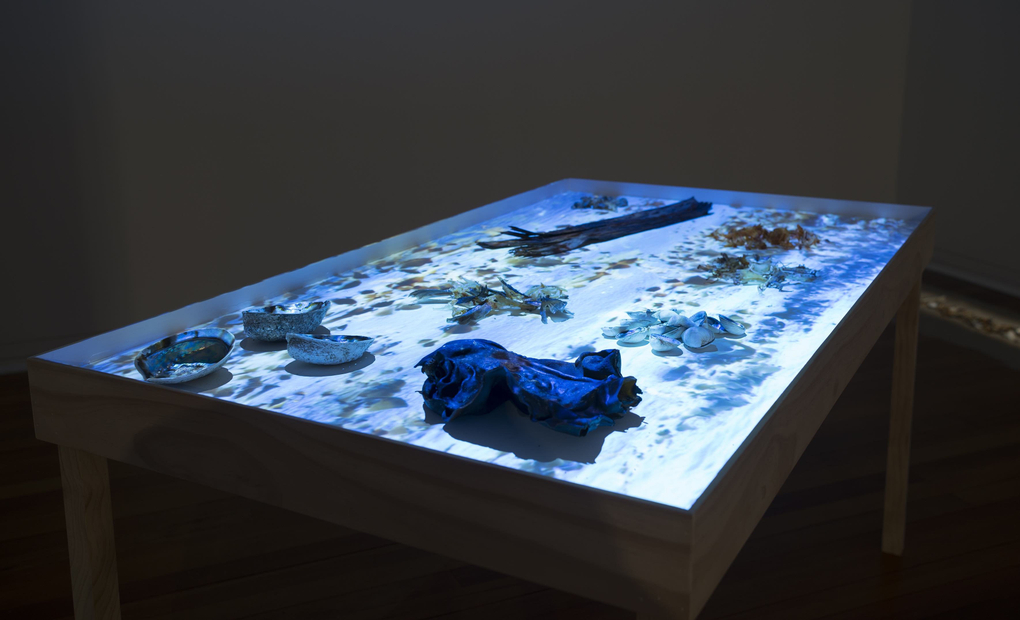

Untitled Midden (2021) Kaihaukai Collective: Simon Kaan [Kāi Tahu, Kati Irakehu, Kāti Mako], Ron Bull (Kāi Tahu, Ōraka Aparima). Mahika kai, midden on table, digital video. Photo: Justin Spiers

Another installation about the search for sustainable kai moana is displayed near-by. In Untitled Midden (2021), the Kaihaukai Collective (principally Simon Kaan and Ron Bull) presents a seaweedy table-work, an edible palette of mauves and greens, alongside a floorwork: a line of sprinkled sand supporting sea-shells and other sea-wrack. Onto the table-top assortment of kai moana remnants, a video of flounder and other seafood being freshly gathered and prepared is projected. The result is a mottled, speckled, glistening theatrical tableau, intended not just to memorialise customary practices of sea-food harvesting and sharing, but to help preserve them.

Juxtaposed is a study in entropy and wastage by Peter Robinson, entitled Urutaka 1-5 (2021), which consists of five large thin grey plastic sheets, sliced and slashed and tacked up squarely on a wall. They symbolise a fundamental pessimism about the plastic sargassoes blighting the Moana-nui and the microplastics infiltrating our coasts. Plastic is produced from fossil fuels and is ubiquitous. Where others might use such materials to construct pragmatic totems of regeneration and hope, Robinson's minimalism delivers a wry essay on the sinister beauty of flotsam and jetsam in art-historical end-times.

Many of the artworks in 'A Landing Place' are more about questions, frictions, and differences than about providing definitions or answers. They convey hybrid and entangled connections and dilemmas.

Whakaruku (2021), Simon Kaan (Kāi Tahu, Kati Irakehu, Kāti Mako). Digital photograph on cotton paper, ceramic waka. Photo: Justin Spiers

By contrast, Simon Kaan's Whakaruka (2021) is a benign ten-metre long series of photographic panels, interspersed with silhouettes of small ceramic waka. The mural panels show a glassy expanse of sea in muted marine tones towards the end of the day. The seascape is softly dissolving into the distance under an oyster-grey sky. The ultimate impression created by this lyrical work is of a gossamer-sunset atmosphere, of a last light blissful and serene, with the distant waka eternally voyaging on.

Also evoking a distant horizon, Nathan Pōhio's long, thin, geometric lightbox entitled Te Māku and Māhoranuiatea/The mist and the horizon aligns the traditional atua (deities) Te Māku (mist) and Māhhoranuiatea (horizon), out of which other primal forces might emerge: lightning, rain, Te Ra (the sun). Pōhio's black-red-white dynamic establishes a rhythmic pattern between these colours, which are significant in Māori cosmology; as does Pōhio's videowork Paemanu Ahika (2021), outside in the Gallery's Rear Window exhibition space. The title here refers to both the Paemanu trust and to its new partnership with the Dunedin Public Art Gallery: 'ahika' are the fires of occupation or residency. A stepped design of tukutuku geometric patterning unscrolls along a horizontal, interspersed with the flames of a fire and other motifs.

Many of the artworks in A Landing Place are more about questions, frictions and differences than about providing definitions or answers. They convey hybrid and entangled connections and dilemmas. There are enigmatic, talismanic objects, such as the two-part totemic sculpture, Tūtakitaka (2021), by Madison Kelly and Mya Morrison-Middleton, with its bird feathers, whale-bone, sea-glass, and dried flax raincape. Alix Ashworth provides Ritual offerings Kāitiaki #1, a wall-hung globular creature made from fired white clay and dyed fabric, while other artworks respond to colonial interactions. A gallery devoted to works inspired by the whale (tohora) and whaling, provides meditations on cultural fusion. Martin Awa Clarke Langdon offers three large containers that resemble the try-pots used to render oil from whale blubber, while Vicki Lenihan presents a display of bent steel forms modelled on those made by nineteenth-century iwi who turned sailing ship nails into fish hooks.

Ephraim Russell's mixed-media lightbox work Taki Apakura (lament) (2021) delivers the 1830s pageantry of the deep blue sea in the brilliant hues of a stained-glass window in a Gothic cathedral. It depicts whales in an underwater paradise, a world in harmony, ahead of an encounter with a whaling ship.

For Rongomaiaia Te Whaiti, three oil-on-canvas paintings on the motif of whales are a form of commentary on the relationship between two of her ancestors Kaipaoe and whaler John Robert Brown, with the whale itself becoming an emblem of her family identity as a badge or decal on clothing.

Installation view of Paemanu: Tauraka Toi – A Landing Place [Waka Tūpuna] (2021), Dunedin Public Art Gallery. Photo: Justin Spiers

front: Inside Tamatea (2021) Ayesha Green / centre: Becoming Sound (2021) Lonnie Hutchinson / back: Sticks (and stone) (2021) Keri Whaitiri

Ayesha Green's series of acrylic paintings Tupuna Portraits (2021) develops the notion of familial connections further with a still-evolving assembly of ancestor portraits, painted from photographs of elders by their descendants under Green's direction. In her large-scale work on vinyl, Inside Tamatea (2021), Green invites us to climb inside the eye, the gaze, of the wharenui overlooking Ōtepoti harbour, with a large-scale imaginative depiction of the view from there, from the sky to below the waves.

With her extended family album of portraits, Green emphasises flax roots level involvement, united by her characteristic droll cartoonish style. This flat, poster-look, simplifies in a faux-naive, folkloric manner, but it also promotes a picturesque populism, a tender carnivalesque affection, to suggest a grounded belonging, kinship, the notion of the marae as tūrangawaewae (a place to stand). In these portraits, copying is quotation: a passing-on of tradition and knowledge in transmuted form.

Altogether, Paemanu: Tauraka Toi — A Landing Place, a long time in the making is about the aura, dignity, presence, and confidence of the Kāi Tahu iwi, hapū, whānau. The exhibition is a form of reclamation of the land, seeking to restore its 'mauri', its vitalism. With a theoretical base centred on Māori protocols, it affirms bonds, and repurposes Māoriland curios, inchoate atavistic forms, the animism of the tohunga in a secular context.

Fiona Pardington's large photographic work in the show confirms the grandeur and wairua (spirit) of such found objects as albatross feathers from the Taiaroa Head albatross colony, while Areta Wilkinson's metal sculpture of an interstellar 'space-waka', sprouting antennae and suspended from the ceiling, brings to mind Afrofuturism: that art-movement blend of technology and optimism about the future constructed by African-American artists. Wilkinson's work asserts the nomadic legacy of the first Māori navigators travelling through space and time.

For Beverly Rhodes the exhibition is way to honour her tūpuna (ancestors). Her sky-view oil-on-canvas painting shows the Otago Peninsula, nestled on the horizon and glowing red, while above, spreading its long wings, soars a white albatross 'searching for a tauraka toi', as the wall label states. The land is depicted in a red ochre shade. Red ochre or kōkōwhai is a kind of mystic mark-maker throughout this exhibition, a way of signalling mana whenua. Tactile earth, its traces weave in with the exhibition's narrative to link a thousand years of art-making in Te Wai Pounamu.