It’s been a few months since I’ve attempted the journey from Te Whanganui-a-Tara to Tāmaki Makarau—the lingering pandemic corridor of airports and large populations a good reason to stay away. However, there’s no denying the energy of the city, and finding myself in town for a weekend of CIRCUIT events at Te Uru, it was time for another whistle-stop tour of shows on now and soon-to-be closing.

At Michael Lett, the upper level of Gavin Hipkins’ solo show, The Deep, includes large wall works, tourist postcards, and posters pasted on the floor. Like a modern day Mesmer twirling his finger in front of the viewer’s nose, Hipkins overlays structures on top of the image; a purple circle over an octopus; a group of Steiner-style blocks over a sequence of New Zealand tourist postcards; a shooting star brought to a halt by the artist’s keyhole framing.

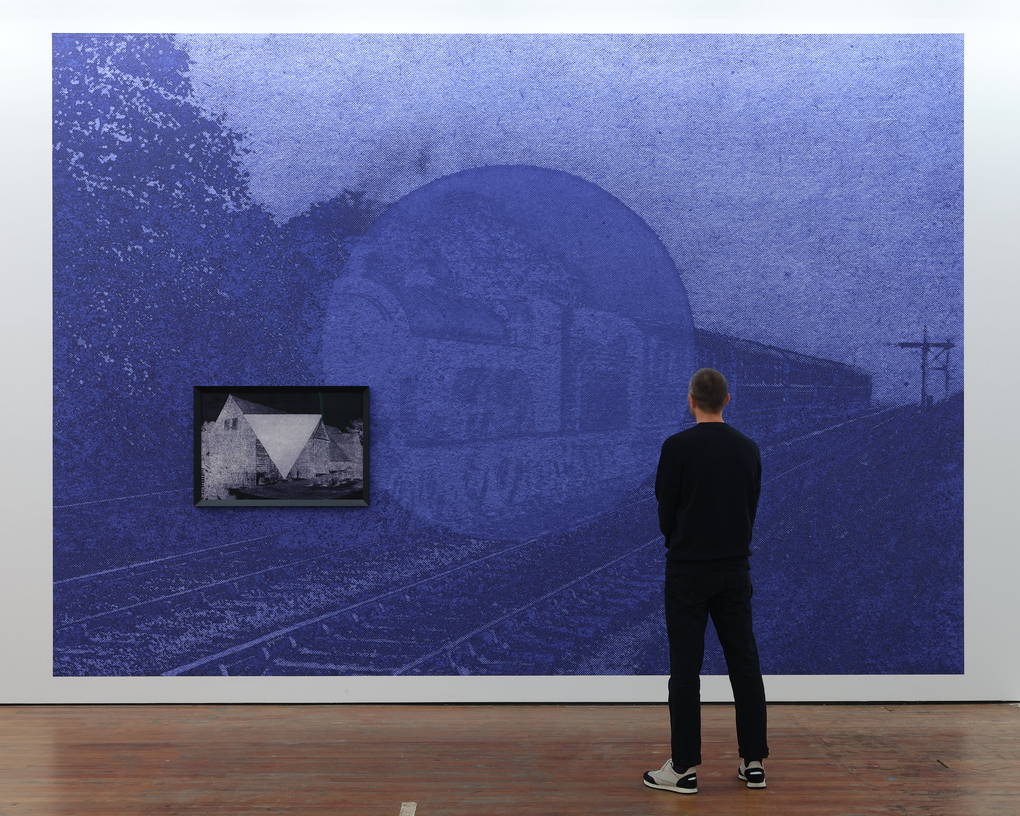

On one wall, the large image of a train recalls the apocraphyl tale of the Lumière Brothers’ 1896 film L'Arrivée d'un train en gare de La Ciotat, the premiere of which so terrified viewers that they reportedly fled the cinema in panic, running from the life-sized locomotive entering the station. As merrily compelling as it is, there’s a lot of debate about the veracity of this cinematic origin story. Similarly, Hipkins plays devil’s advocate with the miracle of image making and industrial reproduction, working the image and our attention.

Installation view of Nocturne (Express) (2022) Gavin Hipkins, Michael Lett Gallery (2022). Photo by Sam Hartnett. Courtesy of the artist and Michael Lett

Downstairs, the video work that lends the show its title, The Deep (2022), drops into the vault like a penny inserted into the slot of a Victorian amusement. “You may speak profoundly. You may pass into another state…” On-screen, solarised and subtly treated images of nature and industry are methodically parsed and separated by black. On the voiceover, a bizarre AI vocal describes the extra sensory abilities of a mysterious ‘sleeper’. Hipkins’ on-screen monologues are typically measured, often laced with some obscure humour that hovers on the cusp of unspoken dread. Here, the voice is almost that of a Scottish woman, but tripping over undigested vowels or letter combinations, remains utterly strange, as if calling from a hidden subconscious. I’ve seen this work before, in both the cinema and a large gallery, but here in the cramped former bank vault an acoustic afterimage pings eerily between the brick walls, adding another layer of aftereffect.

Still from The Deep (2022) Gavin Hipkins

On the adjacent city block at Artspace is mgluw tuqiy na Temahahoi / 找尋迭馬哈霍伊的路徑 / Finding Pathways to Temahahoi (2022) by Taipei-based artist Ciwas Tahos 林安琪 Anchi Lin.

The installation includes six large projections which wrap around Artspace’s walls. Each projection shows images ostensibly set in and around a modern Asian urban world and the industrial fringe. On a barge the lone artist enacts a private ritual of water carrying, and draws spindly lines on their legs, as if inscribing an outer network of veins. In a city they lie down on the pavement in front of a street vendor’s stall, barely noticed by pedestrians or the attendant. In the studio, they lie in naked solitude before a steaming wok on a hotplate, periodically dribbling honey from a jar on their legs. On one screen, a subtitled conversation describes many people killed “during the White Terror”.

The artist’s absurdist performance pieces alternate with a documentary on the impending demise of bees, a speculative leap into an animated landscape. In the gallery itself, a series of clay-coloured ocarinas sit atop plinths like misshapen vegetable tubers, and in another video a group of people laugh and blow into the ocarinas. It’s a sprawling show, moving between registers personal, historical, and ecological, but the scale of the images within the Artspace footprint make for a tough watch. I found it hard to sit with the work without feeling I’m missing something behind me, or on another wall. Do I give up on the bees and ocarinas, or try to take it all in?

Installation view of mgluw tuqiy na Temahahoi / 找尋迭馬哈霍伊的路徑 / Finding Pathways to Temahahoi, Artspace Aotearoa, 2022. Photo by Seb Charles

At Gus Fisher Gallery Turning a page, starting a chapter presents newly commissioned artworks by Jade Townsend, Ana Iti, and Sione Faletau. Under Lisa Beauchamp’s direction, the gallery has been focussed on group shows but here, the exhibition’s title hints at an exploration of three contemporary artists’ individual sense of practice.

Sione Faletau presents two works, Tolu Katea (2020), and a new piece, Ongo Ongo (2022), which, as is his trademark, uses audio recorded on-site to generate abstract kupesi patterns. Faletau’s work moves with shuddering horizons and flickering bursts of line. The past two years have seen Faletau’s malleable work flex to a variety of contexts, from the hundred-and-ten-metre-long Lightship, to a fifty inch monitor in Masons Screen and now to a large walk-in black box. In this instance, we sit on a bench whose proximity to the screen leaves us focussed on the radiant pulsating centre of the work; a gesture which acknowledges the building’s history as a former radio station that broadcast across Tāmaki.

Tolu Katea (2021) Sione Faletau

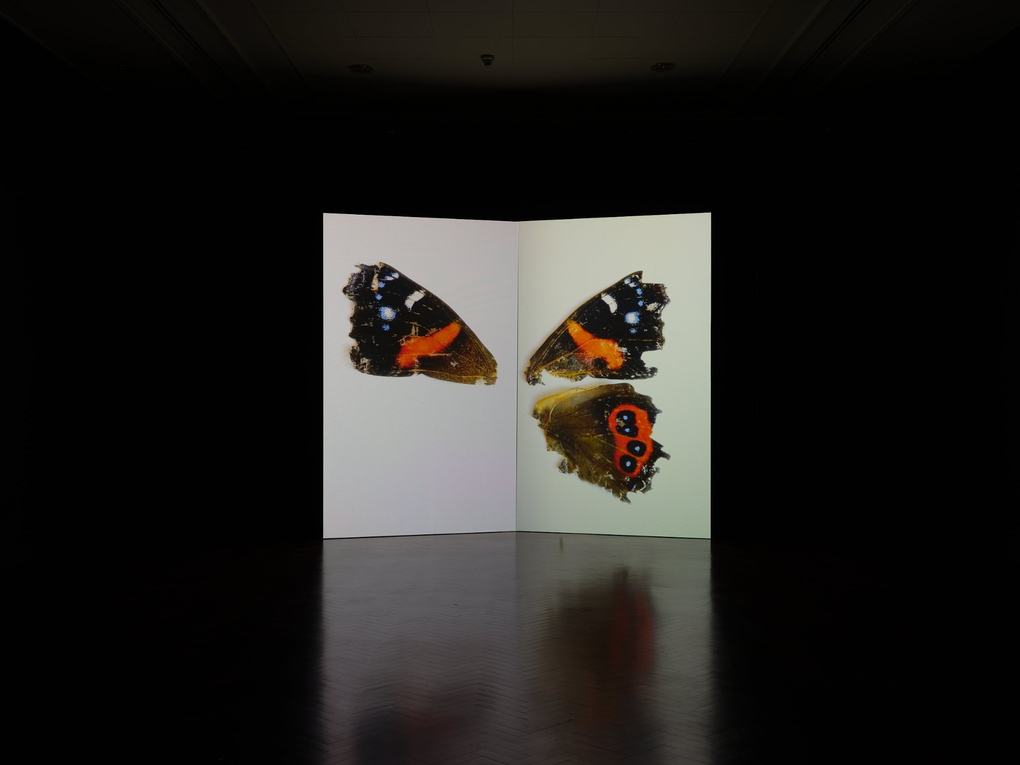

Next door is Ana Iti’s Roharoha (2022). Given a room of its own at the Gus Fisher, the video is projected on a bifolded screen, evoking an open book, and similarly we see hands moving with reverence across pages, with occasional flashes of vertical stripes. Despite the floor to ceiling size of the image, what clinches the success of the installation is the feeling of intimacy retained by the work at scale. It's a fantastic installation.

Installation view of Ana Iti, Roharoha (2022), Gus Fisher Gallery (2022). Photo by Sam Hartnett

There are possibilities a-plenty at Te Uru also, in Otherwise-image-worlds, a group show curated by Tendai Mutambu. Full disclosure, this is a CIRCUIT project, presented in partnership with Te Uru, with works by Juliet Carpenter, Tanu Gago, Ary Jansen, Sorawit Songsataya, and Danielle Brathwaite-Shirley. In our tenth anniversary year the thematic genesis of this project lay in considering how local artists use animation to transcend time, space, and the body’s physical limits. At Te Uru, Tendai Mutambu’s curation encourages the artists to dream big.

Tanu Gago’s 3D video invites us to consider “This glamour... born from the seas of the Pacific... formed in the wombs of warriors... a chance to rebuild, redesign, restore myself... tenacious, this audacity at the tip of my tongue”. Elsewhere, UK artist Danielle Braithwaite Shirley uses interactive game design to invite us on a date as our chosen gender. The tone of How Dangerous is Your Date? (2022) is challenging, combative and funny as hell:

“HELLO THERE DEAR. I AM SO GLAD YOU COULD JOIN ME ON MY WALK AROUND THE COLON OF GENDER”

Otherwise-images-world is full of tightly packed energies, cris-crossing engagements. Juliet Carpenter works between a projected image of a woman in mind-body crisis in a bedroom, while opposite on a CRT monitor we see an animated version of the same. Elsewhere Sorawit Songsataya presents a series of images of Thailand shot by their mother which dissolve into building blocks. The images automatically geo-locate the image taker. Out of the corner of our eye, a holographic screen appears to tumble dry a series of animated blocks in endless recombination.

Meanwhile, Ary Jansen’s work is an all-tabs-open meshing of scattered consciousness and video game worlding. In the top corner we see Jansen playing the game, off-screen we hear the voices of friends near at hand, and on-screen we watch a lone figure navigate their way through post-apocalyptic and mundane environments, from an Auckland motorway to the gallery itself.

,-7-mins-(still).jpg)

Still from Bread crumb trail (2022), Ary Jansen

Back at Artspace, sitting in a corner, is Dieneke Jansen’s Backdoor-Doorbell Studio (2022). Jansen’s work has long focussed on the social good, and this project provides the community with free access to equipment and space to make their own video works. While not in session during this visit, the open access project combines to affirm the legacy of outgoing Director Remco de Blaaij, in siting the gallery literally and figuratively at street level.

And in the tradition of such projects, there’s plenty of material on the doorstep. On this visit, there’s a sense that the ripples of the pandemic pond are still evolving and affecting Tāmaki communities. Many of Queen Street’s shops are empty, the Uber driver tells me how he used to be a successful chef for 20 years until the virus ended his business catering large gatherings, and galleries around town seem to be struggling with a lack of healthy and available staff to mount exhibitions.

Installation Shot of Backdoor Doorbell Studio (2022), Dieneke Jansen. Artspace Aotearoa (2022). Photo by Seb Charles

Meanwhile, at Auckland Art Gallery earlier in the week, Toi Te Kupu: Whakaahuatanga was a two-day wānanga that aimed “… to celebrate and showcase the transformative power of mātauranga Māori as expressed through art, exhibition-making and wider creative practices, while increasing the dialogue between Māori artists on what is critically important in contemporary Māori art right now”. Entry was $335 per head! And students were expected to find $180! As one senior Māori artist said to me, “Does Auckland Art Gallery not realise that Māori communities are traditionally poor?”

Such divergent energies suggest that the idea of ‘post-pandemic’ Tāmaki is a work in progress. Despite this, on the Saturday I visit, there are three talks happening simultaneously at Te Uru, Michael Lett, and Artspace, suggesting that, at the very least, the drive to revive or remake the art community continues.

Conversation with Ary Jansen, Tendai Mutambu, Sorawit Songsataya at Otherwise-image-worlds (2022), Te Uru