Countdown Mountain is a new exhibition by Gabriel White that explores Tāmaki Makaurau over 2021, a period White describes as a 'lost year'. Showing at the Pah Homestead from 17 February–3 April 2022, the exhibition takes the form of a 53-minute film and a 120-page book.

In the film, White performs the role of urban wanderer, his camera alighting on road cones, signage, and inscrutable infrastructure of the modern city. On the accompanying voiceover, White delivers ultramundane interpretations of his subject matter, which are alternately dark, lyrical, and deadpan.

In the book, photos taken by ‘the wanderer’ are humorously paired with short, sloganesque texts by White and playful graphics by Markus Hofko, a combination the artist describes as resembling “a situationist scrapbook.”

Your psycho-geographies are short poetic notes, ostensibly arising from specific moments of perception within urban and suburban landscapes. How are these musings generated?

I'm an intensely verbal person with a restless mind, and in all honesty, I've struggled to find arenas in which to express that aspect of myself. At a certain point I turned to dialoguing with my surroundings. The comments are indeed made in the moment, freehand (although I do multiple takes). I find that a spontaneous comment made in a half-bewildered state often says more than I initially realise, and generates unexpected connections. Of course, I end up producing far more material than I need, and it’s in sorting through and editing the material that a less naive artfulness comes into play.

As I understand it you started working with this form in 2001?

Yes. I moved to Melbourne at the age of 29. Soon after I arrived, curator Emily Cormack invited me to be in a group show with other New Zealand artists. My work had me wandering around Melbourne musing away to a camera. It was a loose, idiosyncratic, but witty journal. Since then I have made several films in dialogue with Auckland. Aucklantis (2008) and Oracle Drive (2013) are perhaps the best known.

What is Auckland for you? How do you differentiate between the Auckland out there and the one that is developed in your works (often with a classical allusion thrown in the mix)? Do you have a grand unified theory of Auckland?

The Auckland of these works is an imaginary one. I see all my explorations of geographies as metaphorical for an inner inquiry. I am an Aucklander though, and exploring my own city brings up different feelings and associations than exploring another geography.

At the beginning of Countdown Mountain you say, “The Underworld is often envisaged as a gloomy cavernous place, but it’s actually a lot like Auckland.” You compare Tartarus to Henderson, and Aucklanders to Underworlders.

In a sense—perhaps a polemic sense—Countdown Mountain is a requiem for Auckland. There is a venality about the city, and a sense of a great project that was subverted by opportunism. A beautiful place destroyed by stupid decisions with long term impacts. But the name Auckland, like the name New Zealand, has become passe. We are in the midst of a big shift globally, and I've felt a change in the city's ethos over the past few years. Nevertheless, an oppressive bleakness pervades the city and therefore the work. At one point, I compare the Sky Tower to the Needle of Necessity in Plato's underworld. Another thing the Underworld and Auckland have in common is that there is no unified idea of either.

Countdown Mountain (Prologue) (2022) Gabriel White

For some time, I have been interested in the possibility of urban structure and services to suggest other worlds. Sometimes it is as simple as smelling or seeing something that puts me in Sydney (most often).

We all have underworlds—fleeting, interior landscapes we return to, be it in dreams, reverie or memory. If we are sensitive to these drifting worlds, they can assist us in dealing with our deceptive and demanding outer world. Fiction and poetry can be a technique of negotiating the possible. We should not retreat too far into our inner world, of course.

Recently I read Graeber and Wengrow’s book The Dawn of Everything: A New History of Humanity (2021). The authors make an explicit appeal to a concept which they attribute to Elias Canetti, that ‘Cities begin in the mind’. Canetti speculated that Palaeolithic hunter-gatherers living in small communities must, inevitably, have spent time wondering what larger ones would be like. Proof, he felt, was on the walls of caves, where they faithfully depicted herd animals that moved together in unaccountable masses. How could they not have wondered what human herds might be like? No doubt they also considered the dead, outnumbering the living by orders of magnitude.

So the ‘invisible crowds’ that Canetti proposed were, in a sense, the first human cities—even if they existed only in the imagination. And I think very large social units are always, in a sense, imaginary. There is a fundamental distinction between the way one relates to friends, family, neighbourhood, people and places that we actually know directly, and the way one relates to empires, nations and metropolises, phenomena that exist largely, or at least most of the time in our heads.

What problems or possibilities does this present for you in respect to your poetics?

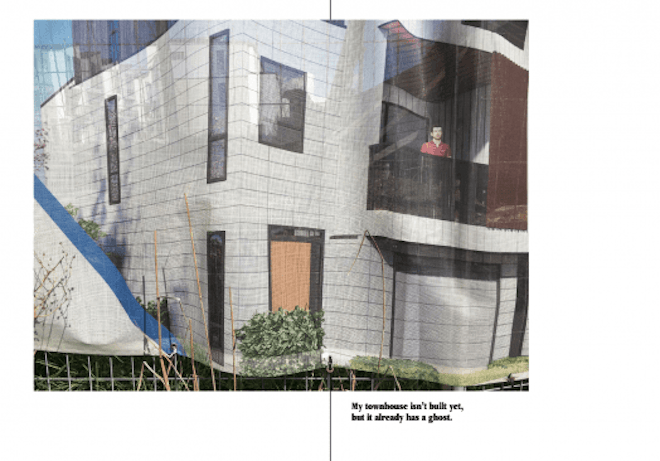

In Graeber and Wengrow’s book the freedom to disobey, to roam, and to reorganise the social structure are of key importance. The first two seem more pertinent to my practice, which is a drifting, hunter-gathering one. I definitely relate to the quest for more social, spatial and ontological flexibility. In many instances, my form of disobedience, my way of asserting my place, is humour. The question of the crowd is an interesting one too. I like to present a landscape that seems oddly uninhabited, or perhaps inhabited by invisible populations. In the Countdown Mountain book, one of the captions reads, "A world of closed doors leaves a lot to the imagination". Another is, "You're never far from isolation". These are really cliches about freedom and loneliness, but they also suggest a sensitivity to the ephemeral, to subtle presences, to things past and things to come. Perhaps we create fictional worlds to give these presences a place to belong.

"My townhouse isn't finished yet but it already has a ghost", page from Countdown Mountain photobook (2022) Gabriel White

In one of your texts, you talk about "Elevator muses". Each muse has a different role; one of them opens and closes the elevator doors, another announces the floor numbers, one acts as the elevator's memory.

Like many of my monologues, the Elevator Muses one works as a metaphor for my creative process, which draws inspiration from the ordinary. Making a monologue often does feel like stepping into an ordinary lift and beginning to play with the buttons. I get stuck ‘between levels’ and have to summon the muses to rescue me.

It reminds me of the monolith in 2001: A Space Odyssey (1968), or the vault in Isaac Asimov’s novel Foundation (1951)—objects which at first are unreadable as a text or ungraspable as a thing, so we guess at their function.

The Mountain abounds in miraculous machines! My favourite are the ‘harvesting stations’, which read drivers’ minds as they drive over cables. I suppose such magical machines could be related to the concept of AI—perhaps I’m making fun of claims that AI could spiritualise machines. Or it could be about the proverbial ghost in the machine. It could also be referring to the worship of machines, or the machine as a modern mythic archetype. There’s a clip where I talk about robots as the ‘indigenous tribe’ of the mechanical age: “They don’t live in our world—we live in theirs”.

At one point you drive down a road called Omega Street, and describe it as the central space in a labyrinth—does the big O hold a scary monster for you? You also say that the end point is in the middle of things, “in the middle of the journey of life I found myself in a dark forest.”

Ironically, the O has ended up in the middle of our modern alphabet, as if it’s been swallowed up. That clip is partly about being swallowed up by whatever 'work' is. I was thinking about words like labour, elaborate and labyrinth. Work is perhaps what adults get lost in and sacrifice most for, especially the sense of play. There is another clip about my "dream résumé", where I muse on what it means to work and what it means to have dreams—to have adventures, fantasies, even past lives—to play! In the book there is a picture of a grey wall. The caption glibly states, "I found an immaculate grey wall. I wanted to follow it. Take the day off." My preoccupation with greyness is a commentary on the joylessness we are asked to accept in our lives, which is perhaps the monster in the centre of the labyrinth.

Still from Countdown Mountain (2021) Gabriel White

The film is structured alphabetically of course and the circularity of the omega echoes the etymology of the word encyclopaedia. The film’s form actually resembles what is known as a “commonplace book” more than an encyclopaedia. Commonplace books have a long history, but are essentially notebooks for jotting down miscellaneous stuff gleaned from other texts using an alphabetical ordering system. The ‘harvesting stations’ I mentioned earlier could be a metaphor for this rather arbitrary but very open process of compiling information.

Often in your work you invent places, such as the suburb of Finnegans Wake. The novel Finnegans Wake (1939) is a famous circular book, a book of everything. Of course, shifted, translated, the signs in the book may not yield their referent.

I think we have returned to the idea you brought up earlier, that cities begin in the mind. Maybe they end, or become immortal, in the mind too—the way we replay the history of, say, Athens over and over, reinventing and renewing it in our minds. In a sense, all places are invented—especially the ones we feel most attached to.

Sometimes in making this kind of work, wandering around a place like Penrose, I feel like a benign intruder. I’m investigating and reimagining spaces others identify with and this can be awkward because my activity may feel transgressive. I hope that my activity is not judgemental but inventive. I suppose my invention of a sleepy suburb called Finnegans Wake parodies suburbia generally as a fool's paradise that panders to mediocrity and habit. But as I say at the end of the film, “The residents of Zodiac Street keep strange pets”. Wherever we live, we are all strangers, all residents of strange inner worlds.

In one of the final clips, I muse upon a medley of street signs that start with the letter z, and refer us to places at the end of the earth, or perhaps those drifting territories we carry within ourselves. It’s a sweet irony that the exotic often bestows a kitsch sense of sleepy domesticity onto a place. What could be a better illustration of the inventedness of place?

Still from Countdown Mountain (2021) Gabriel White

I just really like this image—it is beautiful—it seems appropriate to close with it. Is there anything else you would add?

Perhaps I could return to the thing about retreat and the urge to escape the mundane world. It might be that my comments in the midst of suburbia and the industrial fringe seem to seek, almost desperately cut, a way out. I think of it more as a process of transformation or transmigration. The Yellow Mountain clip this image is a still from connects to another clip entitled Three Types of Rock, where I compare states of matter—igneous, sedimentary and metamorphic—to states of mind. To be in a metamorphic state is the essence of life.

Matthew David Wood is an arts administrator who has worked for the Wallace Arts Trust for 12 years. During that time he has curated a number of exhibitions for the Pah Homestead, including Parlour Games (2016). He has a background in Social Anthropology and English literature. He has been an editorial assistant and provided annotations for Charles Spear’s Collected Poems (Holloway Press, 2007).