What is sovereignty? Is it innate and universal, or something to be contested and won, in a given place and time?

The following panel discussion took place between Greg Dvorak, Lana Lopesi, and David Teh at CIRCUIT's Sovereign Pacific/Pacific Sovereigns Symposium at Pātaka Art + Museum in Porirua on 24 October 2020. Dr Greg Dvorak backgrounds a history of militarisation across the Northern Pacific, and artists whose practice subsequently utilise non-material or relational methods to assert their culture and community, sometimes in the context of wider regional histories, or international art events. Lana Lopesi speaks from the position of the Pacific diaspora in Aotearoa to outline the multiplicity of Pacific identities, an ethic which centres the artist as the maker, and the “fight for the joyous and the beautiful and the imaginative, the speculative as political.”

The panel begins with presentations by Greg Dvorak and Lana Lopesi and is followed by a discussion and questions from David Teh.

David Teh: Welcome Lana and Greg. What I’ve noticed today is a tremendous reluctance to talk about sovereignty, or at least to put it in those terms. And this is very interesting to me. On one level, there’s clearly an anti-Colonial aversion to the term. On another, there’s the question of the difficulty of translation. [This] of course can be a Colonial problem, but it doesn’t have to be. There’s also great creativity in thinking of alternative terminology around the ideas suggested by the word "Sovereignty."

I’d like to say why I felt it was important to have Greg in this conversation. As you saw with my presentation, I was determined that although this is a highly charged discursive area in Aotearoa New Zealand, the discussion should not be confined to that context.

Our sovereignties are more and more intertwined, whether we like it or not. With that in mind, I was really keen for somebody who knows about the Pacific region in great detail and who has published a lot of scholarly research to speak, but also [someone] coming from different points of view.

Greg is from a European/North American background, but has lived for a long time in Japan. And I think even in that triangle, you find a lot of the possible contradictions and difficulties in transferring these terms. So with that I hand over to you, Greg. Thank you for coming.

Greg Dvorak: Thank you very much, David. I also have some qualms about the word Sovereignty, depending on how we talk about it in the register of Northern Oceania. But first, I want to explain a little about whom I am to be talking about this.

I am an American although I haven’t spent much of my life in the United States. I grew up in the Marshall Islands, which at the time was part of the US Trust Territory of the Pacific Islands. At that time, the United States felt quite entitled to make sense out of the lives of Marshallese people, who would go on to become citizens of their own independent Republic of the Marshall Islands; and the people of what eventually would become the Federated States of Micronesia, the Republic of Palau, and the Commonwealth of the Northern Marianas (which ultimately remained an American territory).

These are geographies which I think are somewhat unfamiliar to people in Aotearoa New Zealand. Partly because of the vastness of Oceania. But also because those histories are very much divided by empire and colonial legacies—the British Pacific, the French Pacific, the Japanese Pacific, and so forth. My history is traveling between these places, but also trying to triangulate and navigate through those spaces in a way that is supportive to my friends and colleagues in the region. And again, to wonder even what the region is in the first place.

These are people who navigated great distances to get there. That legacy continues today, but there’s a lot of awareness and lived experience of the intense colonisation and militarisation that continues up to today.

So which Pacific are we talking about? These "Nesias" that we have, I think are highly problematic. Many in Aotearoa might agree. But if you look at the ‘Polynesia’ part of this, in some ways, it culturally makes a lot of sense, in terms of the shared cosmologies, languages and so forth. And that Polynesian story is very powerful, even through places like French Polynesia, where the French language generates yet another sub-region.

My focus [today] is really in the area that has been called "Micronesia", although I would argue that this is a reductive and marginalising term—"micro" meaning "small islands that don’t really matter." When I look at this region, I’m compelled also to ask: “What other forces have tainted this, or brought this about in the first place?"

But there are other Nesias. There’s a "Japanesia" that a lot of people don’t even think about. Japan colonised Northern Oceania and has its own fraught history of thinking about and Orientalising Oceania, which is often not even brought into play in these conversations. Japan’s colonies in Micronesia stretched all the way from Palau across to the edge of the Marshall Islands, which is a huge swath of the Pacific. And the Japanese were in Micronesia for about 30 years as a relatively peaceful civilian presence, including Okinawans and Koreans who had been brought there and stayed as colonised subjects.

Then, you have Americanesia, which, from its inception, is very much about an extreme militarisation that normalises the presence of military bases, planes, helicopters and missile tests. I grew up in Kwajalein Atoll where missiles are still tested every single month. There were 67 atomic tests conducted in the Marshall Islands, which totals something like one Hiroshima a day for nearly ten years between 1946 and 1958. Not to mention that similar things were happening down in French Polynesia. And New Zealand was very engaged in the Nuclear Free and Independent Pacific movements of the 1970s, ‘80s and ‘90s.

But there tends to be an idea that Northern Oceania is just a very American place. And I want to argue that first of all, that’s not true. Secondly, we can think about this region more expansively, as something like "Macronesia" rather than Micronesia. Because this region—if we could call it a region—is so marginalised to begin with, there’s actually a lot of potential for them (speaking collectively) to think outside the box.

These are people who navigated great distances to get there. That legacy continues today, but there’s a lot of awareness and lived experience of the intense colonisation and militarisation that continues up to today. It becomes an inflection in the way that artists and thinkers from the region are able to do doublespeak, and to work in spaces that are much more ephemeral and intangible, and in some ways, very oriented towards ritual and something that is probably not seen.

This is a vast region with thousands of islands; it is not just about Guåhan (Guam) and Hawai‘i. Today I’m more interested in talking about those islands in between, and reflecting on the curatorial practice that I’m involved with right now for the Asia Pacific Triennial number 10, which is its 30th year, and scheduled to open in late 2021.

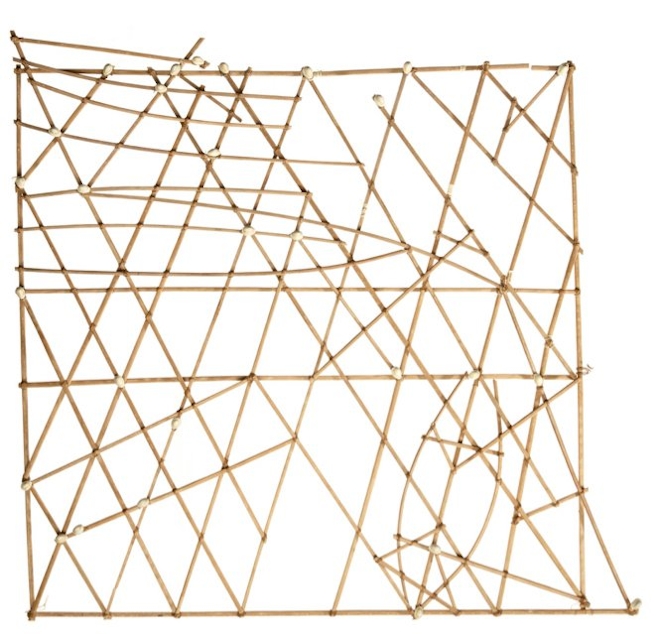

Marshallese Navigation Chart. Courtesy of Department of Anthropology, National Museum of Natural History, Smithsonian Institution, E432083

This is a Marshallese navigation chart. Sometimes it’s called a stick chart. It has many different names, depending on its purpose, it could be a rebbelib or a mattang, and there are different kinds. This object was never meant to be brought on board a canoe. It’s an object that for Marshallese navigators was to be memorised, but it also is unique to every single navigator. The little white spots are shells that mark different intersections. But these different markings are not geographic points on a map in a Western sense. They respond to the energy of the ocean.

In fact it’s quite reductive to talk about navigation in terms of just the people of the sea and the flows and the currents. To a navigator, this is the representation of ocean swells, of textures, of echoes. You have to think in terms of physics; echoes that are rippling off of islands, that could be felt with the body, embodied knowledge thousands of miles away from a sight of an island. It alludes to something that is perhaps more evocative of the unseen.

With APT, we’ve been working with navigators, singers and artists who work more in performance, or make work that might not last very long. We’re thinking about energy and current and how that can be reflected not only in water waves, but also sound waves, air waves, all kinds of energy dimensions. Navigation has been revived again and again. And it’s a very important metaphor for sovereignty, for decolonisation, for reclaiming the narrative, for many people throughout Oceania. But this is particularly true in Macronesia, where they mastered some of the most elaborate and nuanced forms of navigation.

Navigation Revival at the Festival of Pacific Arts, Guåhan (Guam) (2016). Photo by Greg Dvorak

This is an image that I took in Guåhan in 2016. It’s a very moving moment when the canoes Navigation Revival at the Festival of Pacific Arts, Guåhan (Guam) (2016). Photo by Greg Dvorak arrive, because it’s at the Festival of Pacific Arts, and navigation is understood as an art that is embodied, practiced, felt, known, shared among the community.

I want to point to this navigation not only as a metaphor, but also as a sense of psychological and intellectual sovereignty in terms of: the agency of postcolonial awareness. Micronesians have been deeply influenced by America, But they’ve been there, done that. They’ve also been influenced by Japan, by Spain, by Germany, but more importantly, they have always known who they were in terms of their own cultural identities and ancestral knowledge. Most of them are independent countries now, and they all very much know who they are and where they are headed; as they navigate sovereignty itself.

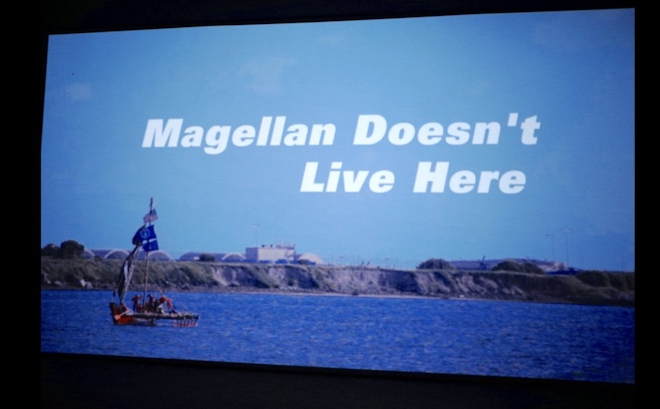

Still from Marquita Micki Davis, Magellan Doesn’t Live Here (2017) Greg Dvorak, 5 min 11 sec, Digital Video, Sound

I want to talk a little about decolonisation and demilitarisation. Micki Davis is a Chamoru artist we featured in the Honolulu Biennial. She made a film called Magellan Doesn’t Live Here (2017). The first place that was really actively colonised (and it was literally 500 years ago) in Oceania, by Europeans, was Guåhan. It was known by Magellan as the "Island of the Thieves" because Islanders took canoes up to his boat and started pulling at the little bits of metal they found. He declared that they were all thieves and launched a big massacre on the village of Umatac in Guåhan, killing a large number of people, and then actually feeding their flesh to his starving crew. Really brutal and horrible stuff. This is what underpins the very first colonisations of the Pacific. Micki Davis’ work speaks back to that, and to that navigation and what that means in that Guåhan context, where things are so heavily militarised, so heavily colonised and so forth.

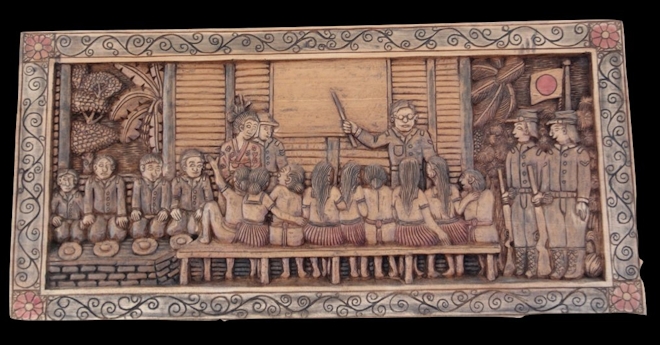

United Artists of Belau (UAB) (Palau) (2009) woodblock carving

Left is a piece from United Artists Belau, a Palauan collective from the 1990s whose work references militarism, colonialism, and so forth, using different kinds of vernacular practices. Wood—carving in Palau is quite big, as it was incorporated into the elaborate narratives carved into bai meetinghouses, and later popularised for the Japanese handicraft market by Japanese artist Hijikata Hisakatsu. These are very physical pieces.

Medad El Bai (Coming of Days Bai) (1990) Samuel Adelbai (Palau), acrylic on canvas

This is Palauan artist Sam Adelbai’s painting from 1990, a traditional bai meetinghouse in Palau, but painted with Pepsi cans around the columns that are holding up the Bai. There’s a Jesus face at the very top representing Christianity, and there’s a big mushroom cloud in the middle of the white triangle representing nuclear testing in the Marshall Islands. Palau was one of the most courageously outspoken nations that resisted American nuclear tests and the dumping or transport of waste in their waters—a ban that is written into their constitution. So this work is speaking back to globalisation, Americanisation, this American hegemony that is in their living room from day-to-day. Beyond Indigenous artists from Micronesia, there are other Indigenous artists (from the region) who are also speaking to this kind of Trans-Pacific American presence, enmeshed with Japanese involvement.

_Greg-Dvorak_CIRCUIT-Images-2.jpeg)

Hawai‘i Ho’okuleana (to give responsibility) (2016) Kapulani Landgraf (USA)Photographic collage

This is a more recent collage work by Hawaiian artist Kapulani Landgraf that was featured in the last APT. The names that you see here, Kaho‘olawe, Mākua and so forth, are all places that have historically been rendered inaccessible to Hawaiians because of American military activity.

ゴジラ/ɡɒdˈzɪlə/ (2020) Jane Chang Mi (USA), 96 minutes. Digital Video, Sound

Jane Chang Mi is an American artist currently based in Los Angeles, but she works around Hawai‘i and recently in Japan. This work above, entitled ゴジラ/ɡɒdˈzɪlə/ (2020) takes all 32 hours of the Godzilla films (1954–present) made by the Toho Company in Japan, edits out the monsters and leaves behind the soundtrack. All of these movies are layered on top of each other, revealing repeated scenes of violence. Even without the monsters, you have this soundtrack of militarism, sounds of Japanese bureaucracy, and we get a sense of an enmeshed Japanese and American embrace that is still happening today. If you live in Southern Oceania, this is possibly not apparent. You wouldn’t really sense just how intrinsically Japanese and American everything is in that colonial layer. Islanders in these spaces are moving ahead with different ways of unpacking that.

Lucky Dragon (2012) Arai Takashi (Japan), Daguerreotype photograph

In Japan, Arai Takashi is a daguerreotype artist who is also referencing colonialism and militarism, in the Marshall Islands particularly. This is a beautiful work about the Daigo Fukuryū Maru, a boat that was irradiated by the American military nuclear tests in the 1950s during the Castle Bravo test at Bikini Atoll. In fact the boat was Japanese, which revealed to Japan that America was still continuing its disturbing and disgusting tests that caused so much horror in Hiroshima and Nagasaki. I would also add to this that other Japanese artists, as well as Okinawan artists like Ishikawa Mao or Ishikawa Ryuci, also create art that also references these kinds of entanglements.

I would like to talk about expansion of region through poetry. Craig Santos Perez is a spoken word artist from Guåhan. Praise Song for Oceania (2017) is a video work that is an ode to Oceania in all of its complexity, honoring both the colonial and the indigenous, but also all of the sickness, the trouble, the radiation, the horror of all of this stuff. I really encourage you to find his work online and listen to the power of these voices. Here we see an installation work from the same year entitled (De) Fence.

As a Chamoru person from Guåhan, Craig’s acts, his motions of decolonisation are very effective in terms of honouring the voice. And again, voice is something that is sometimes not noticed in art. Again, these are sound waves being projected out that can be encoded, that can subvert colonial voices, colonial noises. They also speak back to the traditions of navigation, which is all about knowing different chants, being able to recite these different spaces and places on the ocean’s surface and so forth.

Working with the Asia Pacific Triennial in Queensland, I’ve been really honoured to work with Pacific curators, Ruth McDougall and Ruha Fifita. Ruth and many of her colleagues began a way of curating work from the Pacific that was more workshop-based. So much work that we see of the Pacific comes from amazing diaspora, in places like Auckland, for example, or Wellington and so forth. But going into those islands also, and trying to see their more independent understandings of what matters in art, really takes time and a lot of energy.

APT spearheaded a number of these different onsite workshops. A precedent for this was the “Women's Wealth” workshop that happened in Bougainville, an island which has voted for its independence but is currently part of Paps New Guinea. For this, co-curator Sana Balai worked with several women over the course of two weeks, having all kinds of discussions, making work together, and sharing stories. And eventually those works were acquired by the Queensland Gallery and became a part of APT 9 (2018).Now we’re using a similar model in ‘Macronesia’, and we’re thinking more along the lines of finding different artists who can speak to this larger expandedness, because Micronesia is not a cohesive whole, it’s extremely diverse, it’s extremely complicated.

Still from I Matai (The Dead) (2017) Mighty Island (Guåhan)

This is a still from a video collective called Mighty Island in Guåhan. They’re mostly Chamoru artists, and this is a still from their work I Matai (The Dead) (2017).

The Rookie Boys in Kosrae, Federated States of Micronesia. Photo by Greg Dvorak 2019.

We’re also working with a collective called the Rookie Boys in Kosrae who are basically gospel singers, and they’re all men. On first impression, it would seem like it’s devotional music, but this powerful singing all throughout Oceania—especially in the islands of Micronesia—is very complex and very nuanced. It goes way beyond Christianity. It’s very much about celebrations of life and survival and overcoming all kinds of obstacles.

Marshallese woven flowers with recycled wartime Japanese wires. A public domain photo from the Marshall Islands Government

These are flowers made out of wire, but the wire is actually harvested from the earth on annMarshallese woven flowers with recycled wartime Japanese wires. A public domain photo from the Marshall Islands Government Kathy Jetn̄il-Kijiner (Marshall Islands) at Asia Pacific Triennial 9 (2018). Image by Greg Dvorak island called Wotje in the Marshall Islands. During World War II Wotje was one of the places most militarized by Japan.

Women work together taking Japanese military cable and recycling them into flowers, which has become quite an art form in the Marshall Islands. This is another way that everyday art can reference decolonisation and demilitarisation.

I wanted to draw this to a close by talking a little bit about art as ritual, and to honor the work of my friend and collaborator, Kathy Jetn̄il-Kijiner.

Kathy Jetn̄il-Kijiner’s practice began with her work as a spoken word artist. Her voice is extremely charismatic. It has a lot of energy. She is slowly owning a legacy of being tapped into a history of chanting, storytelling and navigating in the Marshall Islands. There are many people who have that past, but it has been devalued by colonial histories.

Kathy Jetn̄il-Kijiner (Marshall Islands) at Asia Pacific Triennial 9 (2018). Image by Greg Dvorak

This is her performing a piece at the APT 9. In workshops, she studied with elders to make these jakied mats, which utilise very sacred weaving practices in the Marshall Islands that have recently been revived by a group of women. Kathy took that training and then deconstructed this mat. She talked about this as a ritual reflecting on the harm that was done to Marshallese women through nuclear testing; thinking about reproductive health, about post-partum depression as a metaphor for the birthing of a new nation in the Marshall Islands; and pushing back against American and Japanese hegemony. Really powerful, deeply encoded stuff.

Anointed (2018) Kathy Jetn̄il-Kijiner (Marshall Islands), 6 min 18 sec, Digital Video, Sound. Image by Dan Lin

Another work of hers that really speaks to this is Anointed (2018). In this work, she actually goes to Enewetak Atoll where there’s a big nuclear dome that’s covering up all of this nuclear waste from the 1950s. And she places these small coral stones on this irradiated space, exposing herself to a lot of radiation. But that act of putting stones on a tomb is a very Marshallese way of honouring ancestors, honouring the dead and making some sort of connection between these different spaces. She’s demarcating, re-territorialising space, and also making that very American, very militarised landscape something that is Marshallese. She’s returning it to the Marshall Islands.

She’s also a climate change activist. She went to Greenland and worked with Aka Niviâna, who is also a poet and climate activist, from the Inuk Indigenous community there. And they mourned the loss of land in Greenland caused by the melting of ice, and the rising of the seas in the Marshall Islands that was caused by that. Both exchanged gifts as part of this ritual, mourning what it means to live in our world today.

Rise: From One Island to Another (2018) Kathy Jetñil-Kijiner and Aka Niviâna, 6 min 31 sec. Digital Video, Sound. Image by Dan Lin

That’s pretty much what I wanted to share with you today. I hope that gestures a little bit towards that expandedness, breaking down some of these different assumptions about what colonialism might mean, what militarism might mean, what Macronesia versus Micronesia might mean. And trying to honour that maybe there is some hope for the word "Sovereignty" within this, because I think that there is interest among people in the North Pacific to really, really push away the United States and really speak back to it. These are very strong voices.

Hawai‘i and Guåhan are respectively a state and an unincorporated territory of the United States. But the Marshall Islands, the Republic of Palau, and the Federated States of Micronesia are independent. For them to actually break away from US control as they did in the 1980s and 1990s was a very, very big thing and required an incredible kind of bravery. They are currently in what we call Compacts of Free Association with the United States, which means that on paper they are independent, but they’re still in many ways influenced by American hegemony. The United States has the right to put military bases there and do whatever it wants in some ways, but at the same time they have seats in the United Nations, they can speak up, they can speak back. They would consider themselves to be "Sovereign", but that all comes with many strings attached.

David Teh: Thanks very much, Greg. I have lots of questions, but I think we should move straight on to Lana.

I’d like to hear her point of view on some of the things that you’ve raised, but also to hear about what she’s been working on. Lana.

Lana Lopesi: Thank you both David and Greg.

To preface, I wanted to do a bit of bridging because like lots of us, I’m trying to work out how I can meet this conversation. Both in relation to what’s been said throughout the day, to the Artist Cinema Commissions that I saw yesterday, but as a broader conversation.

I’m going to come at it from a very particular localised idea, specifically to my position of being in the Pacific diaspora here in Aotearoa. Firstly, the oneness notion of sovereignty is important and interesting. However, all enlightenment-era philosophy (which was trying to make sense of the world through this Euro-centric notion of universality), fails to take into account the multiple ways of being.

I’ve been thinking about Walter Migno lo’s "decolonial option" as a way of fracturing the assumptions of universality. Mignolo argues that one approach to modernist thinking is through a reversal and localising of it. That [concept] offers me a theoretical break from this modernist sovereign narrative [and an opportunity] to rescale it.

To be able to have conversations around sovereignty from Indigenous points of view, from Pacific points of view, we need to do this rescaling of modernist sovereignty so that it’s at the same size of other ways of seeing, understanding and practicing sovereignty. The other thing I wanted to talk about was the "colonial imaginary", because what we’re calling sovereignty has this inherent hegemonic and supremacist quality.

I think of the colonial imaginary as being the way in which colonised peoples and places have been imagined and historicised in art, literature, science and cartography. As you pointed out Greg, this is still something that Pacific artists and scholars have to contend with today.

So these modernist ideas, we can’t just break from them, we have to address them, especially when we’re talking about ideas of sovereignty within creative practice. In that rescaling, we can’t underestimate the ongoing power and pervasive nature that the colonial imaginary and enlightenment/modernist-era thinking is having today on our artists.

The fact that the future APT is still contending with this is evidence that it’s still something they have to think through. I felt like I needed to do that for grounding because there’s a risk that we can be talking past each other instead of having a generative conversation around these ideas that I think we’re all invested in. I don’t think we can assume that there is a shared sense of sovereignty. There’s not, and we can’t assume that all artists feel like they have a sense of creative sovereignty to start with either.

I’m finally going to talk about art. I’m pulling that term "creative sovereignty" from Métis art critic David Garneau and how he uses it in terms of the category "Indigenous art." I’m also thinking with Samoan/Persian artist and curator, Léuli Eshrāghi’s notion of Sovereign Display Territories, in which he talks about a need for Indigenous artists to have control over "Sights," "Sites," and also Citation in the sense of possessing creative sovereignty.

My current research is looking at contemporary Moana artists from a digital native generation and their art specifically made between 2012 and 2020. There is a really clear expression by the artists that coming through art school, they were trained and disciplined to make art in a way which satisfied the appetite of a larger and mostly white arts community here in Aotearoa and [in] the institutions.

And so, not only is there this bigger, pervasive, colonial imaginary and matrix of power built into all of the mainstream systems and structures that we’re part of here in Aotearoa, but there was also the sense that Pacific artists felt they were being trained and encouraged to make [art] in a way that had a legible Pacific politic and also involved the reproduction of Brown trauma in a way that served audiences, but depleted themselves as artists. For this particular group of artists, their creative sovereignty is a notion of safety. [It] comes from a mode in which the artist holds that sense of power, or finds a mode of practice, which centres themselves as the maker—rather than a mode of practice which tends to the gaze of others. Their sense of creative sovereignty has no real legible form, which to me is a really expansive component. It looks like speculative futures and Ahilapalapa Rands’ Lift Off (2018).

Still from Lift Off (2018) Ahilapalapa Rands, 3 min 23 sec. Digital Video, Sound.

It looks like illegibility and a sense of joy and Louisa Afoa’s wallpapers. And it can look like exchanges which centre on Indigenous modes of kinship rather than colonially-mediated relationality, which is a really hard task across Oceania when there are so many divisive histories of colonisation, which impact our very ability to talk to each other. This creative sovereignty makes room for other people’s points of view, as well as other creative sovereignties.

Installation view of Orion (2017) Louisa Afoa. Image courtesy of Sait Akkirman

I feel like I’m really trying to fight for the joyous and the beautiful and the imaginative, the speculative as political. These qualities in artwork, I don’t think would often be interpreted through a politic of sovereignty, but when you think of all the things in which these artists are working through to get to a space where they’re actually producing in a mode which builds them up and doesn’t deplete them, I feel like that’s the ultimate example of creative sovereignty.

I wonder then, if creative sovereignty for racialised bodies is working against the way in which you are expected to work. It’s being a glitch in the system, it’s being disruptive. Because you’re not expected to work in ways where you have control over that voice. Even getting to that point where you actually know what it is you want to make, away from the disciplining that we go through, and the external pressures of responsibility to wider community, is actually quite a radical thing to advocate for.

So I suggest an expansive notion of sovereignty is actually a fractured one, in which sovereignty as we use and understand the notion in English is needed or required to shrink into size in amongst many other things. And only if we accept that, can we have these relational, generative, expansive conversations across modes and ways of being.

David Teh: Thanks very much. That was very rich. Greg, if you’d like to respond? I think there’s some obvious points of connection and parallel between your two contributions. I’d really love to hear what you thought.

Greg Dvorak: Thank you so much, Lana.

When I talk about region, I’m very troubled by these boundaries and also the kinds of conversations that are happening in different kinds of ways throughout Oceania. I even have found recently in my own practice that I like to use both Pacific and Oceania. "Pacific" really references Magellan. He started that whole ball rolling with calling this place the Pacific.

Margaret Jolly has referred to this as "double vision", where you have both thinking in those colonial terms or contending with that baggage, but also really wanting to carve out space. So when I say "Oceania", it’s sort of more in terms of that Epeli Hau’ofa-ian gesture towards constant expansiveness. But in terms of being a glitch in the system, being disruptive and carving out those spaces, that seems to be something that is common among all of the artists that I’ve worked with. I don’t know if I would call it sovereignty, but it has something to do with having space for each other’s conversations, being able to engage with each other, listening for each other.

At the Festival of Pacific Arts in Guåhan a lot of people were really looking to Guåhan as a new space [for] opening up these conversations. I saw a lot of people coming from different parts of Oceania, particularly a big contingent that was coming from New Zealand. They wanted so much to engage. But just to cite the example of some artists, they were being bussed around on these American school buses, sleeping in these public schools way off site, very close to a military base. While discovering the vibrant, exciting communities that they were hoping they might find, they were also discovering that they were in a highly militarised landscape and recognising just how hard it could be in that space to resist that, to work in that, to carve out these spaces. So I guess I want to really push for specificity. There are very different things happening in different places. And opening up common dialogues and conversations really matters right now. I have to say too, in my work at the Honolulu Biennial, working with Māori and Pacific curators I’ve discovered that the conversation has expanded so much in Aotearoa. These conversations around art really haven’t been able to happen in Northern Oceania very much at all. It’s almost as if there needs to be some playback of what happened down South. Although people have been enduring very similar struggles, both North and South there’s wonderful collaboration around art all kinds of stuff happening down in Aotearoa that Northerners have not been able to experience. The same kind of art infrastructure really hasn’t been able to be facilitated under the constraints of American hegemony. There isn’t enough funding for it either. There’s really nothing that supports any of this stuff. So just in terms of practical matters, these are also really important issues.

David Teh: Thanks, Greg. I wanted to ask you guys one more question.

One of the things you talked about is intangible forms, and you spoke of an orientation towards ritual or devotional idioms as representing an important space for non-colonial agency. Then Lana, in your talk, you referred to forms that couldn’t be named so easily. In both of these, there’s a resistance to the kinds of reification that go on in an art market, art history and perhaps under the purview of art institutions. And of course, you’re both actively engaged in negotiating these things.

Lana, would you like to respond to what Greg has said about that, because I’m also conscious that the glitches that you’re advocating for might actually take us away from ritual or devotional forms.

Lana Lopesi: I think firstly, it’s not one or the other. I wouldn’t really separate them, but just acknowledge that the artists I’m talking about are participating within the western art market—as we are also today—but they also come from ways of being, and seeing the world, which are not of that. But artists are artists because they love form and they love making. And that’s really exciting too.

So I also feel personally a bit of a hesitancy to separate them, but rather, to let Indigenous artists be complicated and have all these multiple facets to them and their experiences.

And I think that’s actually been the struggle of my research. I know that there is something in these artists that makes them make in the way that they do. We have this relational concept of "Va" in Samoan and the [artists] sit in these relational spaces, which are not just the art community they’re in, but also the families they come from.

It’s the lineages that Carl Mika addressed before. It’s the wider socio-political things going on, it’s Indigenous global kinship structures or relational things that people are negotiating in this Indigenous international art market. There are all of these things happening and it’s really hard when we then have to catch them in the English language, or we have to translate something intangible into a tangible form, like writing. (I’m a writer for a living, and I know that there’s an irony there.)

I’ve talked about creative sovereignty today, but I’ve actually understood it or come to it through a Samoan concept of Mau, which I think is possibly an equivalent, but maybe that comparative argument is not that helpful.

Ultimately this is a western art history and it is the English language. And I think Carl Mika addressed it too; sometimes you just can’t fix things. I think that’s something that we could lean into, rather than constantly try to fix, even though that’s what our universities and our jobs as writers and curators want us to do, but we could actually harness and hold on to that.

David Teh: Greg, I wonder if you could just talk about your experience with art institutions? You’ve been involved with some big ones. Do you feel as though the prospects for leaning into the non-material and the intangible and the informal, do you feel like that’s improving in contemporary art organisations or do we have a long way to go?

Greg Dvorak: That’s a great question. The jury is out, but I’m optimistic.

Working with APT, I’ve seen curators I have met there have to negotiate incredible bureaucracy with the Australian government and various conventions of how museums and galleries are expected to function. Under those pressures, how do you talk about something that is actually very ephemeral, that could only happen in a certain way? That could be very much about respecting spirits, dealing with something that is not about the material, really? I think they’ve made big strides in that direction. There’s more and more of an honouring of that or trying to find some way of dealing with that. But I’m also pessimistic. For example, the Oceania Exhibition that happened in London and Paris in 2018 was a really incredible wide-reaching exhibition, but at the same time so much in that was about material history and colonial collecting. “Material stuff” is not the only art that actually has value.

In Western art circles, it’s common for curators to seek out some individual who’s doing some really cool, funky practice that’s very visual, very material, very tactile, something that is just going to wow viewers and collectors. In many local communities throughout Oceania, and particularly in rural Northern Oceanian places like Palau, the Federated States of Micronesia, and the Republic of the Marshall Islands, the emphasis on art is of ten different. You’re finding people talking about art, (but) usually more in the context of culture and community or genealogy. So their art is more about the connections that they have with each other, about genealogies, about the spaces in be- tween, and often also the non-visual and performative. Up in Micronesia, and especially in low-lying atolls, there is not as much rock or wood or other materials to make work with, and the environment is so harsh that it does not last. Much of their art has long existed in the world of song, dance, and ritual, or in the weaving of intricate mats and other important objects. It is art that is more embodied, performed, passed on than art that can easily be displayed in museums and galleries. So even encouraging people in the “art world” to even notice what constitutes art in Micronesia.

Biographies

Dr. Greg Dvorak is Professor of International Cultural Studies (History and Cultural Studies, Art Studies, Gender Studies of Pacific and Asia) at Waseda University in Tokyo, where he is based in both the Graduate School of International Culture and Communication Studies (GSICCS) and the School of International Liberal Studies (SILS). He is co-curator to the Asia Pacific Triennial 10 scheduled for 2021.

Lana Lopesi is Editor-in-Chief for the Creative New Zealand Pacific Art Legacy Project, a digital-first Pacific art history told from the perspective of the artists. Lana is currently a PhD Candidate at Auckland University of Technology.

David Teh is CIRCUIT’s 2020/21 curator-at-large. David is a curator and Associate Professor at the National University of Singapore, specialising in Southeast Asian contemporary art.

Download the Sovereign Pacific Symposium e-book

You can download the full Sovereign Pacific/Pacific Sovereigns Symposium e-book here [PDF].