‘The largest Moreton Bay fig tree in New Zealand is in Monte Cecilia park,’ T. had told me on the phone earlier, when I’d spoken of my plans for the day. I google this and the New Zealand Tree Register tells me that this specific Ficus macrophylla was planted circa 1850, which would make it around 172 years old.1 There are a handful of photos posted in the online register, dated 2011. I click on the thumbnails, hoping to get a better sense of the tree’s stature. Only in one of the images is there a person visible for scale reference; in the others the frame is consumed by thick, tentacular roots and branches, sprawling out from both ends of its torso. I read further that the Monte Cecilia Moreton was planted by William Hart, who bought the property in 1844. It apparently has three trunks and is around 50 metres wide at its crown. I’ve seen smaller versions of the native Australian species, still impressive, at Albert park in the city centre. Their accommodating, cavernous buttresses are often seen to flank the possessions of rough sleepers, wedged in between the crevices—mink blankets, sleeping bags, deconstructed cardboard boxes.

It was this Moreton Bay fig I held in my mind, a speculative image with only a few thumbnails to go on, as I walked up the wide, curving driveway to the homestead on the grounds of Monte Cecilia. Auckland Council promotes this park as ‘an authentic experience of a typical old English countryside estate’.2 It was an unseasonably warm day in early September, with unthreatening clouds framed by optimistic pockets of blue sky. Coming here demanded a sort of staunch, militaristic discipline; clenched-jaw while thinking about the concept of charismatic facts, as defined by The Distance Plan:

Charismatic facts are magnetic; they move from speaker to speaker, gaining velocity and weight the more they circulate and the further they travel from their point of disciplinary origin. Charismatic facts can be used by speakers in many situations, including academic, political, or informal conversation. … Charisma has a dubious history, generating shimmering auras of distortion around persons and objects. And yet, in a time of fragmented political will, charismatic facts offer a medium for organisation, mobilisation, and circulation.

The homestead housing Xi Li 李曦’s show, THE GENERATION OF THE HYPERREAL, is a late 19th-century Italianate villa design based on Osborne House, the former residence of Victoria and Albert in the Isle of Wight.4 The contrast couldn’t feel more pronounced, more at odds with what I’d seen of Xi’s work in the past—the pulsating futuristic city simulation of Spirit Ether (2021) on my computer screen; the seductive 3D-animated digital shrines forming Ritual of Subject (2021) at Artspace Aotearoa.5

Spirit Ether (2021) Xi Li

It’s hard not to absorb an inflated sense of grandeur walking up the u-shaped staircase, with its polished wooden handrail and curved Victorian balusters; the sunlight gently filtering through the massive arched stained glass window in blue and red. Everything is outsized—a floor-to-ceiling deconstructed pattern packet by Philip Trusttum; a metres-wide gilded Max Gimblett quatrefoil, hung just below the ridged ceiling cornice; a pair of tall, lustrous, spiky ceramic forms by Virginia Leonard that sit within the alcoves on each end of the landing, recesses once occupied by statues of biblical figures.

‘The writer is necessarily either God or Priest’, writes Trinh T. Minh-ha. ‘As long as the belief in the sacred origin of writing and the religious principle of hidden meanings prevail, there will be a need for “veracious” interpretation and commentary. The Priest’s role is to transcribe and/or explain as truthfully as possible God’s confiding voice... Holy inspiration or faithful elucidation.’6

Xi talks about the mythologising of contemporary culture, questioning, ‘When the frenzy of self-creation has created an ardent and addictive fantasy about a phenomenon, can we understand our own value system and form a new narrative in it?’ Of ‘the fantasised relationship, for it is itself intertwined with an insatiable hunger, ecstasy and longing…’7

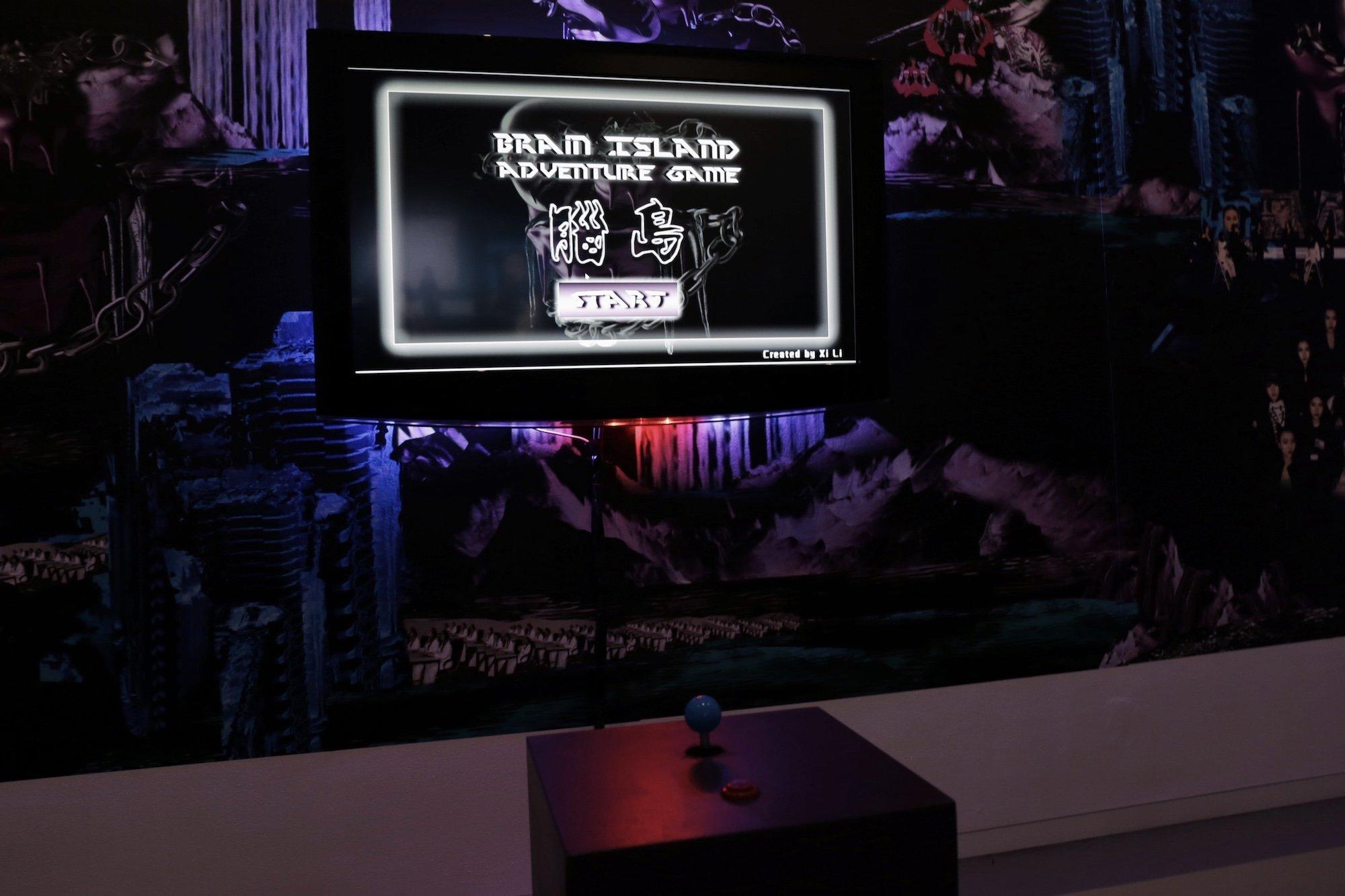

‘This is an Atari-style controller,’ M. said. ‘They were big in the eighties.’ He was gingerly toggling the little blue joystick with his right index finger; his right thumb slightly outstretched, poised at the ready on the red button below. I could see the cursor moving correspondingly, though slightly too smooth, too quick. It seemed that the joystick was hypersensitive to the slightest tilt, and it took a bit of backtracking to get the cursor to land exactly where you wanted. We scan the different character options: Manager. Messenger. Instructor. The Punisher. Divine Power Brain God. Self. Archetypes of the Brain Island generation. Each enacted by a Xi-avatar in a different fit and style, and introduced through a short blurb of character traits. I couldn’t put my finger on the aesthetic of the game’s interface—it was maybe a mashup of Y2K, 3D, retrofuturism, glitch, vaporwave.

‘A bit of cyberpunk, too,’ M. starts. Xi is three years younger than me, enough of a gap for me to feel the discrepancies in our cultural references. I clumsily google these genres, as though reading a two sentence summary and hastily scrolling through the image results could adequately place me in the spirit and complexity of the movement past.

M. presses his thumb into the concave indent of the red button, selecting SELF; the affirmatory exaggerated ‘clunk’ a nostalgic punch in the gut.

introduction: the main character, representing the body of cartesianism. image: black phoenix and dragon dress, necklace made of plastic tube. personality: curious about the world, easy to imagine and fantasise.

A click-through narrative unfolds. What happened? Where am I?

There are cold walls and chains around, monitors and displaying everywhere... This does not seem to be a real space at all.

(Looking around, I was surprised to find strangers who looked like me.)

Brain Island? What exactly is going on!!?

A dialogue with the Instructor, who assures, After this trip, you are eligible to choose to accept the rules of the Brain Island, or leave to return to the real world.8

I imagine washing up on the shores of Brain Island. Except there are no beaches here—the island is only a glistening metallic purple mass, suspended alone in space, dripping with stalactite forms and lovingly tethered with molten silver chains. Commandeered by an invisible force, I glide through a glitching infinite archway.

I’m wishing for an isthmus; emerge instead at the Divine Power Brain God Region, where two Xi-avatars dance ritualistically, slightly asynchronous, on either side the scales of justice. A consistent, high-pitched ringing in my ears, interspersed with a repetitive pealing melody; dissolving to stare into a gently rippling luminescent pool.

Omniscient and omnipresent, she is everywhere and understands everything at the same time; she follows her own or her characters’ outer expression and inner conscience simultaneously; she sees the present, past, and future of all events; and, above all, she has the power to dissolve the opacity of life. Eager to create a meaningful world and/or to unveil her ignored/censored deeper self, she adopts a series of strategies liable to ensure a transparency of form through which content, intelligibly constructed, can travel unhindered… In many cases, she labours at confiding/confessing herself or at cutting herself sparingly into fragments and distributing them among her characters, with whom the readers may in their turn identify themselves. Charged with intentionality, writing is therefore disclosing (a secret), and reading is believing.9

In The Agency of (Planetary) Feeling, Josephine Berry talks about the contemporary erosion of feeling, the loss of communal life, of relating to natural and social environments with reflexivity and an implicit reciprocity. Where acute environmental and sociopolitical breakdowns heighten ‘a feeling of sickliness caused by contracted receptivity and diminished vitality in a rigidified environment’, she asks:

How can we solve, or are we already solving, the feeling of being powerfully “out of gear with [our] surroundings” and yet straitjacketed by a highly advanced technocratic and necrotic globalised capitalist society, one that deprives us of our vital capacity for normativity in both senses of the word, i.e., the attainment of homeostatic states as well as the freedom to break them so as to adapt continuously through emergent responses?10

Installation Shot: Brain Island: Hyperreal City (2019) Xi Li

Chuseok falls on the 10th of September this year, a Saturday. My mother and I eat rice cakes and japchae, but I forget to step outside to look at the full moon—distracted instead by the phosphorescent blood moon around which Xi’s Spirit Ether cityscape orbits. Its surface is engraved with the tessellated outlines of dollar signs, snake-like with their forked tongues. An orange glow permeates the streets; a labyrinthine world-without-beings upon floating platforms—home to pedestalled shopping trolleys, spinning Big Macs, limp mannequin bodies, airplanes, high rises, pagodas.

Nature will have its way, just as history will with the real Empire, with domes, palaces, minarets and pagodas. A storm is blowing at the edges of the site, invading ordered precincts devoted to entertainment and instruction.11 (Brian Dillon, on Virginia Woolf’s 1924 essay, Thunder at Wembley.) And Virginia: It is whirling water-spouts of clouds into the air, of dust in the Exhibition. Dust swirls down the avenues, hisses and hurries like erected cobras round the corners. Pagodas are dissolving in dust. Ferro-concrete is fallible. Colonies are perishing and dispersing in spray of inconceivable beauty and terror which some malignant power illuminates. Ash and violet are the colours of its decay.’12

Spirit Ether is a first-person simulation, the kind you might visualise in a dream—somewhat disembodied, nonsensical. The thrumming, polyphonic bass wants to be a sedative, induce a state of hypnosis. But even the blood moon, in the end, is revealed to be nothing more than a flat disc—another element of artifice in this beautiful, lifeless city.

My eyes take a while to adjust emerging outside of the homestead; the sunlight I craved from inside Brain Island warms me, and I feel relief, a power spike. We walk further down the drive through groves of exotic trees, seeking the canonical Moreton Bay fig. It’s there, a short distance from the rear of the building. Beneath is an emerging understory of natives, mainly kawakawa. Their waxy leaves irregularly perforated, caressed by the toothed mandibles of Cleora scriptaria, the kawakawa looper; a trail of glistening silver left in its wake.