"What can you control? Wrong question [...] Where to start? Start in the middle."(1)

— Anne Carson

Author's note: Below is a series of numbered fragments that, when read in sequence from zero to eight, form an essay. But if you’d like, you can start in the middle—at four—and follow the directions laid out in italics to read/write a mirror essay.

zero // read and go to two

A body of water is a broken mirror. We look for ourselves in lakes, rivers, and swimming holes, but glimpse only fragments rippling across their surfaces. Still, we go looking. Says the narrator of Kirsty Gunn’s novella Rain:

"As you came closer, you saw how dark the water was, how complicated by the shadows from the overhanging growth, how the jade insides of the water were flecked with gold."(2)

The closer you look, the longer you look, what was once transparent becomes dark, opaque, consumed. As Gunn writes, by then, "all the rest is water."(3)

one // end here

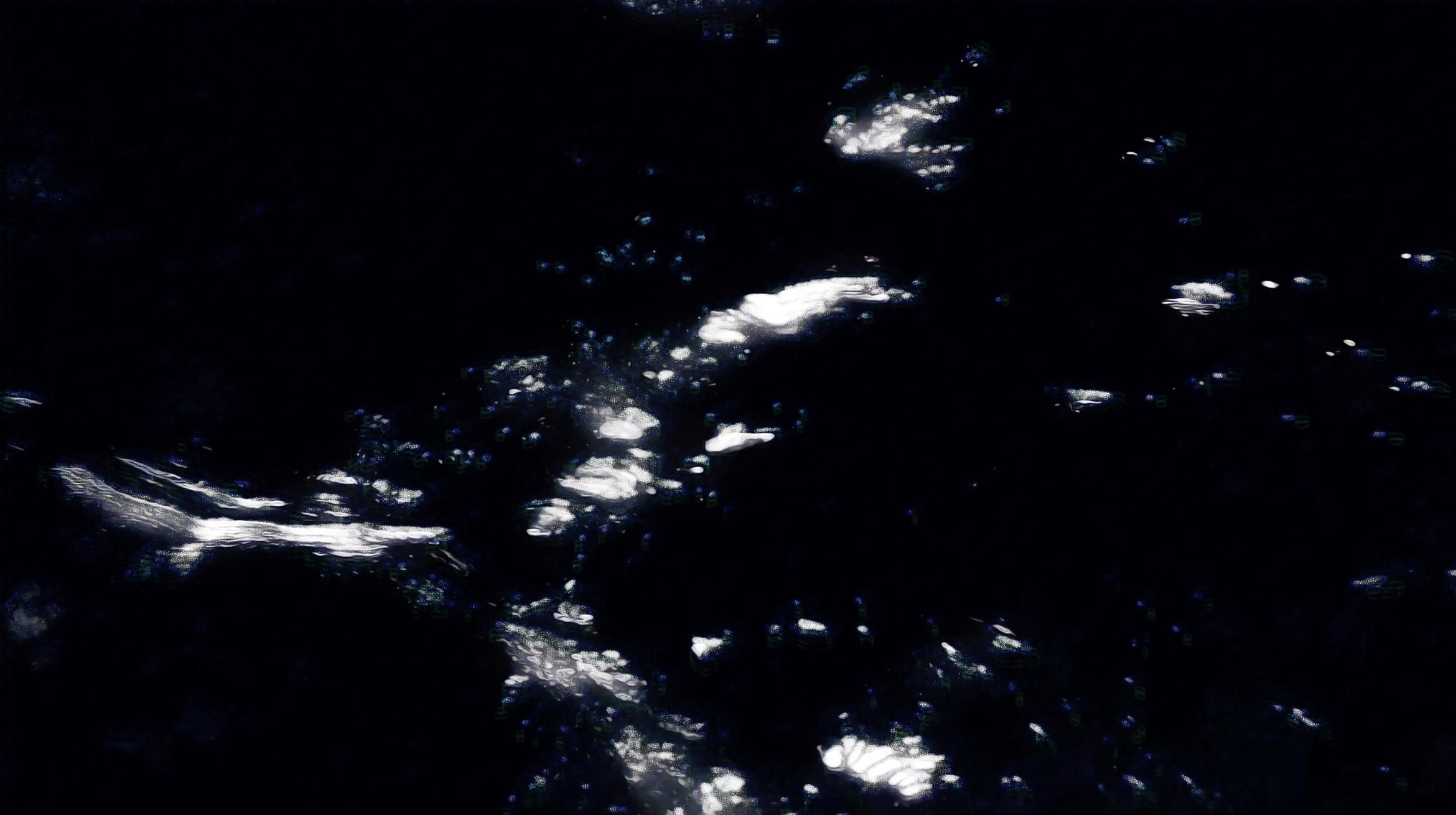

Claus Lucas’ Three Studies (2024) began life as a cellphone video taken of the Emerald Pool in the Te Hoiere Pelorus River, Nelson. This may not be readily apparent to you the first time you see the video; a prism of black, white, and blue pixels pulsating in a luminous, digital abstraction. As white waveforms spawn and stutter across the screen, behind the pixels, water haunts the image as a kind of shimmering, a presence made so illegible it is felt only as an absence. Three Studies is, to borrow Jay David Bolter and Richard Grusin's term, a "hypermediated" video of water.(4) Watching data mosh and subsume the screen, water has likely left your mind, as the paucity of pixels has cast doubt on all but the very materiality of the video itself. Wave-like forms have become waveforms. The medium eclipses the object in visibility.

two // read and go to six

Perhaps, by now, you’ve encountered the work a few times. This time you’ve noticed things look different. The video is the same—black, white, blue, intensely-digital forms colliding and absorbing each other—but now there’s an uncanny movement at play, a rippling like but not like water. The waves are smoother in motion, but this smoothness only emphasises their erratic, unnatural character—how they appear from and return to nothing at random, wraith-like white forms in their place. It's as if the video itself were seasick, lurching in and out of a material, liquid state. You don’t know what you’re looking at, and each time you look, something has changed. This is the game of chance we play with Three Studies—reaching into the bag, never quite knowing what we will pull out.

three // read and go to eight

In his 1957 essay 'Chance-Imagery,' American artist George Brecht highlights how the chance events that artists such as John Cage and Jackson Pollock make use of are, at their core, unconscious selections from a limited "universe of possible results."(5) Such automatic creations, Brecht suggests, embrace the processes of nature, as "nature never deliberates."(6) With this in mind, the sense of uncanny otherworldliness that accompanies Three Studies feels apt. The work is, in a sense, its own universe, an alternate world produced stochastically through a limited selection of digital procedures. In digitally altering our nature, it embraces a nature all its own.

four // start here, read and go to three

By design, Three Studies exists in a vacuum of authorship. Lodged on a screen in a thoroughfare, most viewers will pass by without reading the wall text that attributes the video to Claus Lucas. Those who do will find that Claus Lucas, in essence, does not exist.(7) So who makes Three Studies? Perhaps you do. You, the repeat viewer of Three Studies, even as you engage it for only seconds at a time, gradually (re)make the video. With each encounter, you unwittingly create your own study as its fragments slide into an ever-changing sequence, soundtracked by the click and thud of passing footsteps.(8) Later, unable to remember the work with any kind of specificity, you compose yet another montage in your mind, layering image and afterimage in a palimpsest of matter and memory. Claus Lucas, like so many of the chance-inspired artists of the second half of the twentieth century, has slipped unconscious art-making into the everyday.

five // read and go to seven

If the game of Three Studies is predicated on remaining in a precarious, flow-like state of not-knowing, the more you come to know about the work, the closer the game comes to a standstill. So much of the intrigue rests on a base unfamiliarity with the processes of its creation. For many, however, the art of making by consulting and compiling images and data from a digital archive will seem eerily familiar, calling to mind a very specific and increasingly ubiquitous technology that has found its way into so many corners of our lives.

six // read and go to five

Hito Steyerl has recently called attention to the "mean" quality of AI-generated images.(9) For Steyerl, as a descriptor 'mean' enfolds both the statistical and adversarial quality of these images, images that gather by dragnet all that is stored online into a composite image of an unattainable norm. Read with Steyerl, the push and pull between artist and machine we partake in when viewing Three Studies is more like witnessing AI’s own nightmare, locked in competition with itself, reaching for something it cannot possess.

seven // read and go to one

As entangled with process as Three Studies is, it is difficult not to think of the hidden labour that has enabled its creation. "To produce an AI [image processing] model," writes artist and psychoanalyst Sam Lieblich, "billions of images must be viewed and labelled by human beings."(10) This labour is often undertaken by outsourced contractors, a legion of microworkers. Knowing this, the digital artefacts that linger in Three Studies —the errant pixels, the sudden shifts and lurches—gain a kind of ghostly materiality.

eight // read and go to zero

Though their spawn look and speak as if they are of another, immaterial world, machine learning models share this material world with us. They are not good housemates. The warehouse-scale data-centres from which GPT-4 and the like are trained and deployed are inordinately energy hungry. Millions upon millions of litres of water have been consumed both to generate electricity for and manufacture and cool the servers these models depend on.(11) This water is withdrawn from circulation at a rate that often exceeds that at which it can be returned.

How to describe this feeling, the gradual realisation that Three Studies, predicated on making water visually inaccessible, on blurring and burying water beneath so many digital layers as it oscillates in and out of our perception, that this work was produced by a technology that dissolves water like nothing else before? How, now, to see anything but water?

Claus Lucas, Three Studies (2024)

Matthew Whiteman is a writer based in Te Whanganui-a-Tara Wellington.