Drawing lines through Moana Oceania has a contentious history. Lines marking out nations, regions, territories and time zones were scored meticulously over Te-moana-nui-o-Kiwa / the Pacific by European colonisers, “crisscrossing an ocean,” Epeli Hau’ofa writes, “that had been boundless for ages before Captain Cook’s apotheosis.”1 Through the lines, Oceanic nations were thought into lands that stopped at the water’s edge and, from then on, easy to think of as small, remote and negligible within the global order.

Given this history, any argument for further lines in the region would be right to raise suspicions. sam tam ham (Sam Hamilton)’s Te Moana Meridian is an interdisciplinary installation and research project spooling out from a submission made by the artist to the United Nations General Assembly that would move the international Prime Meridian from its current location in Greenwich, United Kingdom, to Te Moana-nui-ā-Kiwa. The Prime Meridian is the line from which contemporary globalisation sprung, a mechanism of imperial expansion that, in a logistical sense enabled trade and military agendas, and, in an ideological sense established Western Europe as the world’s centre, to which all else refers. Moving it would decentre Western Europe from its long-held perch and establish Te Moana as the new primary site of global timekeeping—one that, the project contends, offers ‘a more equitable and multilateral system for negotiating time and space’.

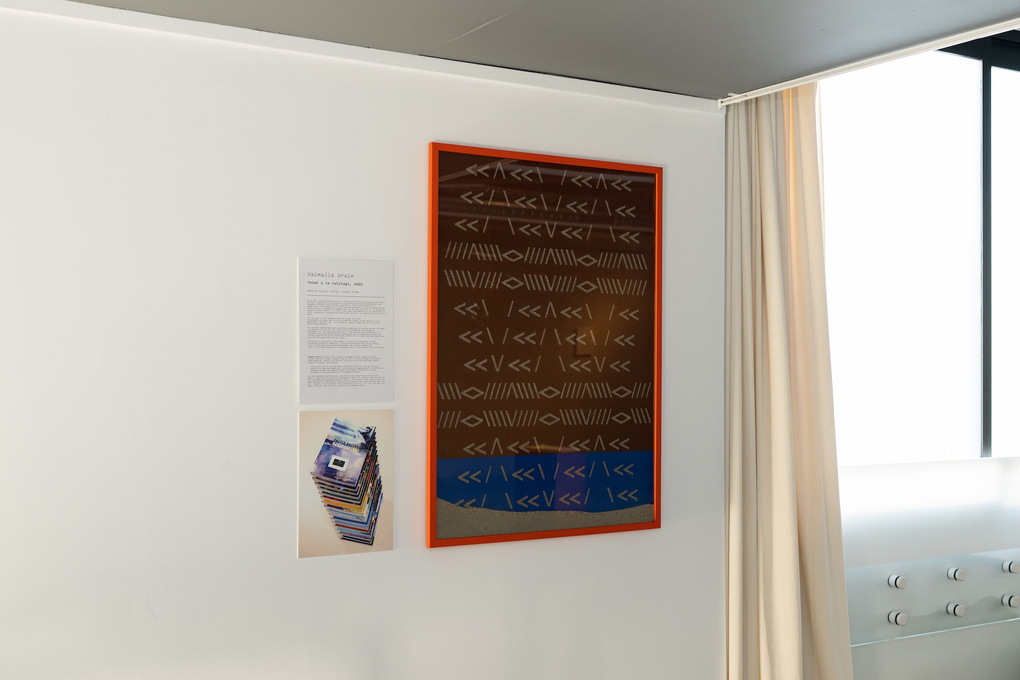

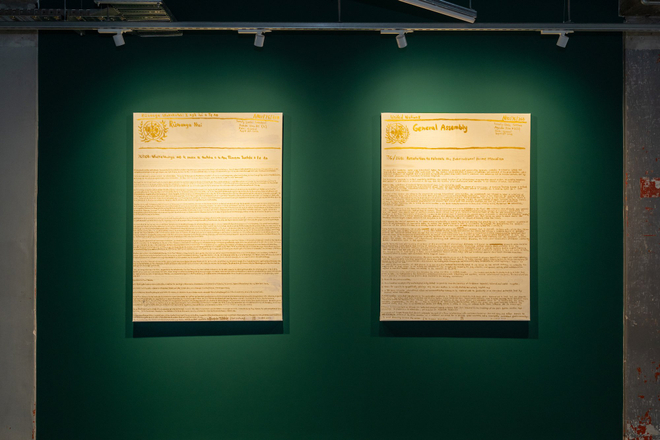

The exhibition consists of archival documents relating to the creation of the Greenwich Meridian in 1884, and versions of the new proposal painted on large canvases in shaky gold lettering, one in English and one in Te Reo Māori (translated by Rhonda Tibble). These new ‘documents’ make the old ones look diminutive. Painting the words makes a public declaration of them, and a corrective to the covert decision made in the back rooms of international bureaucracy. A cover design for the United Nations handbook commissioned from the visual artist, Vaimaila Urale, also features in the exhibition: a large graphic print formed of keyboard characters (< > / \), referencing both Sāmoan tatau and Lapita pottery, as well as computer code.

Installation Shot: Vaimaila Urale, Toime o le Lalolagi (2022). Photo by Seb Charles.

Together, these static elements establish language, translation and acts of address as a context for the moving image work that is arguably the exhibition’s centrepiece. The five-channel projection was directed by Hamilton and made in collaboration with an international and intergenerational cohort of performers: vocalists Holland Andrews (NYC, USA) and Mere Tokorahi Boynton (Te Aitanga-a-Māhaki, Ngāi Tūhoe), dancer Dr Tru Paraha (Ngāti Hineāmaru, Ngāti Kahu o Torongare), and The Lincoln City Children’s Choir (Oregon, USA).

Te Moana Meridian (2022) Sam Hamilton

For an exhibition so conceptually preoccupied with a line, it is maybe surprising that the imagery it repeats and dwells on is the circular form. A spinning globe emerges from the blank, black space at the beginning of the loop; a golden orb, a dawdling Helios, slowly rotating, closes it out; and between them, the various participants perform in round spaces, are choreographed to move in circles, or spin vinyl records on a turntable.

The circle is the shape of the forum, a shape that we supposedly occupy together and on equal footing. The United Nations uses the circle to this effect, to symbolise its goals for international collaboration and diplomacy, for ‘equitable’ and ‘multilateral’ governance. Its emblem captures a view of the planet taken from above the North Pole, the continents splayed out around it like a cheese platter. Surely, the UN’s forum is more ‘equitable’ and ‘multilateral’ than the conference held in Washington DC in 1884, during which Greenwich was named the location of the Prime Meridian by the twenty-six participating nation-states. Less sure, though, is whether the UN’s function goes substantially beyond the symbolic.

The same question could be asked of the project in general: is moving the Prime Meridian more than just an aesthetic or cosmetic gesture? Te Moana Meridian’s key premise is that the meridian’s location is fundamentally arbitrary and technically simple to change, with few repercussions for everyday lived experience. Nature’s timepieces will continue to tick, the video reminds us; the sun will keep rising and setting everyday and the tides will keep ebbing. But the meridian is also hegemonic, itself a symbol (of white and Western supremacy). Relocating it would be to signal that the values of which it is a symbol are not the values we want enshrined in how we keep time and coordinate space. Te Moana Meridian wants the Prime Meridian, passing through the world’s largest body of water, to instead be a symbol of what connects us all, as if the world can be incorporated into what Hau’ofa called the ‘sea of islands’ bound by Te Moana-nui-a-Kiwa.

This is all very utopian, but limited by the singularity of the meridian, which will always confer primacy, however far displaced. This singularity, however, is countered by the five-channel format, viewing which is like trying to see and think across time zones. The image expands across the channels, then splinters into five discrete streams, each documenting an event or performative act separate from the next but simultaneous with it. They amplify and echo one another, so that the voice of Holland Andrews seems to join that of Mere Tokorahi Boynton as they each make their solo address, and the children’s choir and Dr Tru Paraha could be treading the same circuit on the same beach, one after the other. Time expands and splinters with the image. It unfolds and multiplies like bacteria into an image of the world made up of many places, each living to its own rhythm, and impossible to attend to in one viewing.

Édouard Glissant held that, “we cannot discuss utopia with fixed ideas”, so fixing the meridian in one place elsewhere seems unhelpful. Glissant’s way around this was “archipelagic thinking.” “Archipelagos,” he writes, “open us to a sea of wandering: to ambiguity, to fragility, to drifting, which is not the same as futility."2

Nothing about a coastline naturally limits or divides, Glissant suggests, and a horizon doesn’t indicate an end so much as the beginning of endlessness. The ocean is the central presence in Hamilton’s work, more central than the titular meridian, appearing either directly as a setting for the pieces or otherwise incarnated, such as in the conch shell two of the performers hold up as part of their ritual of trans-oceanic communion. The ocean is more central, even, than the titular meridian. In this way, the channels, as much as they give themselves up to be read as time zones, also act more literally as channels through which water passes into the conceptual space of the exhibition—joining untold, larger seas on all sides.

Te Moana Meridian is a mostly symbolic or aesthetic gesture, but it is not futile, because it opens a conceptual space in which, following Glissant, “we can lose time, lose time searching, in which we can wander and in which we can counter all the systems of terror, domination, and imperialism with the poetics of trembling.”3 Into that conceptual space, counter-propositions, (better propositions), can enter. How about we abolish the meridian, as Anisha Shankar suggested at the conference that was programmed to accompany the exhibition? Or move it periodically like we do the Olympic Games, letting it evaporate like Paraha’s footprints do from the sand?

Installation Shot: Te Moana Meridian (2022) Sam Hamilton. Photo by Seb Charles

Many of these subsequent propositions are more convincing and more radical than the one the exhibition makes with its outsized, painterly documents, submitted for UN approval. But in making that initial gesture, it establishes a precedent, or just remembers a mode of thinking and moving in which, as Hau’ofa wrote, “boundaries are not imaginary lines in the ocean, but rather points of entry that were constantly negotiated and contested,” and inches just a little closer back to boundlessness.4