A slow tranquil surrender of the Night Spirits, a knowledge that her body was refreshed and cool and light, a great breath from the sea that skimmed through the window and kissed her laughingly—and her awakening was complete.(1)

I. They are cruel

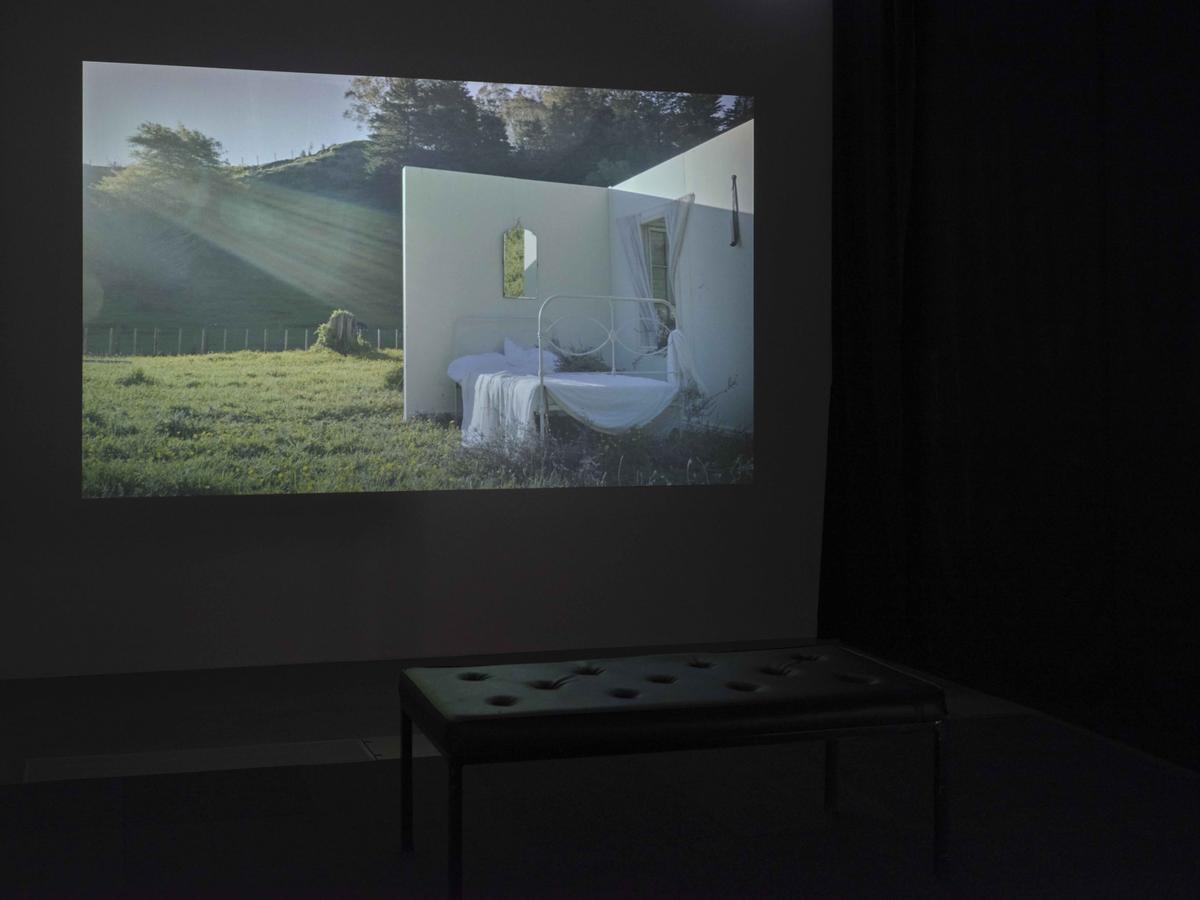

Softly rumpled, slept-in sheets—the persistent summery hum of insects—the song of tūī—a breeze rustling through trees—sunlight streaming, illuminating your set, casting fluid shadows against your bed, the wall, your landscape. Hinemoa’s eager whispers—Marina... Marina!—and with Marina I share a feeling as though slowly waking, disoriented and squinty-eyed after a nap in the sun. Is it...day? Sprays of mānuka litter the bedroom; we peer through the open window framed by sheer white curtains, as Hinemoa exclaims—Oh, come quick—come quick! Your room is hot with this mānuka, and I want to bathe. Your voice, Hinemoa, is impatient, exuberant; holds inflections of youthful innocence. The air is equally stifling in the top floor of the gallery, a humid December day, and the still blue of the Manukau harbour beckons. Cut to a view of our wrought iron bed—its frame painted white to match the bed linen, the dress draped casually over it, and your skin, Hinemoa.(2) Marina’s sleepy groan—I come now.

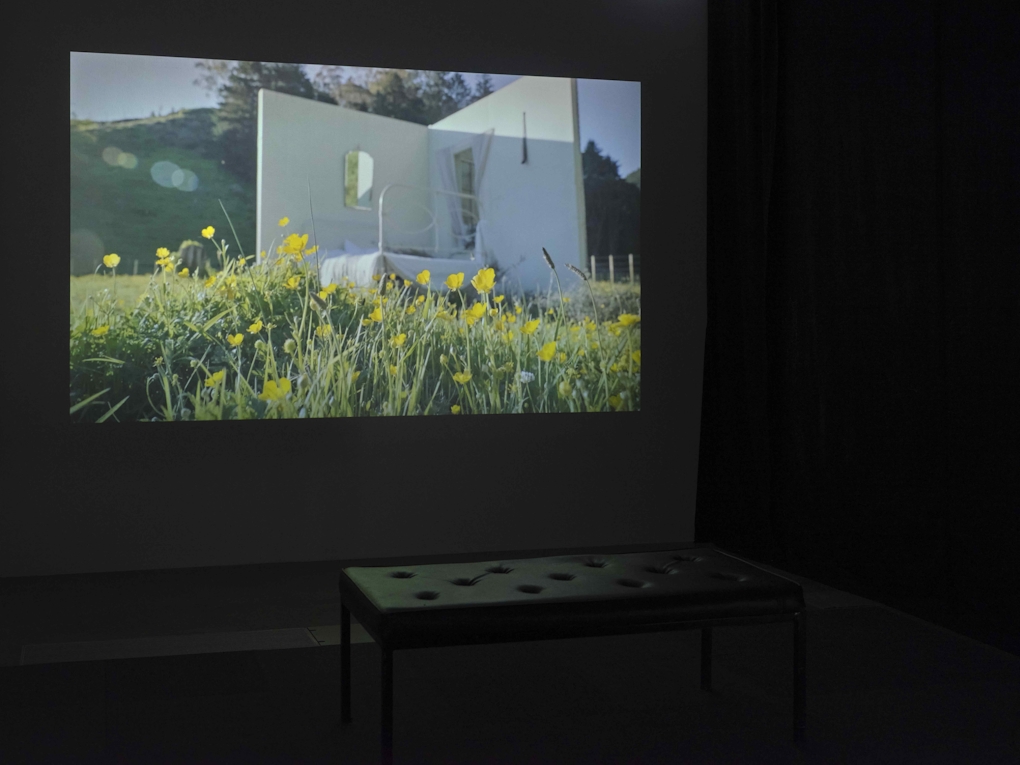

Installation view of Kōtiro, Emepaea (2021) George Watson, at Te Uru Waitākere Contemporary Gallery (2022). Photo: Sam Harnett

Pan slowly around your stage, four walls of a villa erected within a grassy paddock, a foreign footprint in the whenua. See the landscape reflected in a sliver of bedroom mirror; our ears ringing with the crescendo of impish laughter and the eerie chanting of ‘Little Bo-Peep’ until Marina interrupts—Snow maiden–snow maiden! Look at your hair... it is holding the blossoms in its curls. The rhythmic———tick———tick———tick———of an electric fence comes into earshot, an anachronistic punctuation of your soundscape of girlish laughter, insects, breeze; intermittently luring me out of the villa, away from Marina and Hinemoa, away from 1907, the year of Summer Idyll; and suddenly our heads are level with the grass I can almost smell it; level with the heads of buttercups that crane their necks towards the sun; and Hinemoa’s satisfied assurance—You are just where you ought to be.

See the broken window, see the sun through the jagged-edged hole, through the dappled lilac glass, past the washing on the line, which surely must now be dry, as you, Hinemoa, say—But I like not that! I lack that congruity. It is because... you are so utterly the foreign element... you see? See? The hanging beautiful arms of the trees? Marina corrects—Not arms—not arms! All of the other trees have arms. Saving the Rātā with his tongues of flame... Scan your landscape for rātā, but see only foreign trees, and pine forestry—but the fern trees have beautiful green hair... Stand outside the villa, where debris litter the ground; see the open window—an invitation? An intrusion? See? Hinemoa—it is hair. And know you not, should a warrior venture through the bush in the night, they seize him, and wrap him round in their hair—and in the morning, he is dead... We find ourselves airborne, slowly circling your set, now a tiny speck in the landscape; see the surrounding gravel road, the wire fencing neatly demarcating the boundary line; assume the colonial gaze, the romanticising of the pastoral. They are cruel, even as I might wish to be to thee, little Hinemoa.

Installation view of Kōtiro, Emepaea (2021) George Watson, at Te Uru Waitākere Contemporary Gallery (2022). Photo: Sam Harnett

Inhale deeply, anticipating Marina’s directive—Now—we dive! Hold my breath as I submerge my head in the salty water, the first swim of the summer, as Marina continues, clouded by whispers and hums—remember—it is with the eyes open, that you must fall—otherwise, it is useless... fall into the water, and look—right down... those who have never dived so, do not know the sea—it is not ripples and foam, you see. Try and sink as deeply as you can—the eyes open—and then, you will learn... come... come! Paddle desperately towards our refuge the villa, closer, and closer—I am not underwater, but I can hear it, feel the resistance of salt water against my fingers, and the soles of my feet. Breathe in; resurface in the valley. Feel the sting in my eyes, see nothing but blurry shadows. Hear distant opera singing, and Hinemoa, flustered and defiant—Are you mad... mad?! Race me back quickly—I shall drown myself.

What a fright you had, dear. We find ourselves at the table laden with aphrodisiacs; the sun retreated slightly. See how beautiful I am? Come and eat, little one! A peeled boiled egg surrounded by pieces of broken shell, a loaf of bread, an upturned enamel mug filled with live honeybees, blue kūmara, blue pāua in their shells. Our voices become more urgent, almost frenzied—Oh, I am hungry! Eggs, and bread, and honey, and peaches. And what is this dish, Marina?—Baked kūmara———tick———tick———tick———Is it good?—Very—And, you are not afraid anymore? No. What was it like? It was like... like... Yes? I have seen the look on your face—Hinemoa, eat a kūmara! No! I don’t like them, they’re blue—they’re too unnatural—give me some bread!—I eat it for that reason—I eat it because it is blue. Yes. Inspect the plate of unnatural blue, see the silhouette of two honeybees—mating?—against the cross-section of a cut piece of kūmara, and then they are gone.

II. Kōtiro, Emepaea

They are cruel (2021) is a short film, at just over four and a half minutes, but the seamless loop leads me to watch it multiple times before I can place the beginning and end. When I eventually pull myself away from the darkened room and into the adjacent space, I’m confronted by the derelict bones of the deconstructed villa; its four walls positioned in a cross configuration. I walk around the set in circles—once, twice, and look again out the window towards the harbour, and the Waitākere ranges; upon each rotation noticing new imprints on its surface—bodily and temporal traces that bear memories of the summer idyll. A stub of charcoal on the window sill below crudely blackened swathes of wall, flaking paint exposing bare timber, the cracked window, grubby fingerprints—yours, George?

Excerpt from They are cruel (2021) George Watson

I look at your villa as you present it—symbolic of a colonial ideology that gives rise to settler domesticity, and the possession of land and property. Think about how you problematise the naturalisation of a provincial New Zealand gothic, as an outstretch of the Victorian visual vernacular. Think about the words of Tyson Campbell and Julia Lomas, considering the ‘spatial imprints of Western disciplinary institutions such as the church, the villa, the military, and agricultural settings on unceded Indigenous territory’.(3) I look up the two-storey Thorndon villa in which Katherine grew up, the villa you can now visit as an historic attraction; its yellowish-cream cladding matches yours. Yours, here, carries the grief of something abandoned; grief for an extractive industry that saw the accelerated destruction of ancient native forests to build structures such as these; grief for the home rendered inanimate in the absence of the earnest intonations of Marina and Hinemoa. See Hinemoa’s name scribbled in cursive pencil on one wall, like school desk grafitti—tagging, memorialising; a gesture of authorship, or ownership? Little foolish one...

Hinemoa, Marina. Maata, Katherine, Carlotta, Kathleen. I remember these names, glimpsed you painting them on the wall in kōkōwai and iron oxide in a room last year using wool bale stencils.(4) Remember these names, magnified among the names of your whānau and tūpuna; animated in huge LED gothic lettering atop land that was once not there, reclaimed from the Waitematā harbour.(5) Remember Carlotta, your butterfly suspended from the ceiling by meat hooks, kōwhaiwhai cut out of her wings, white satin ribbons trailing from her abdomen. Carlotta; one of Katherine’s secret names for Maata Mahupuku (Ngāti Kahungunu, 1890–1952), her school friend and likely lover; the subject of Summer Idyll, her unfinished novel Maata, and numerous diary entries—I want Maata. I want her as I have had her – terribly. This is unclean I know but true. What an extraordinary thing – I feel savagely crude, and almost powerfully enamoured of the child.(6) Currently reading Moyra Davey, and think of her attraction to diaries, letters and lists as ‘fragmentary’ written forms:

"It’s the concreteness of these forms, the clarity of their address, that appeals and brings to mind Virginia Woolf’s dictum about writing, that “to know whom to write for is to know how to write.” I am similarly drawn to fragments of an artist’s oeuvre, a single image in a magazine or brochure. I tear these out and hold onto them. No doubt I also like the miniaturisation, and the possibility of possessing the thing."(7)

Wonder if Katherine attempted to miniaturise Maata, to hold on to a piece of her by writing her into fiction. And in Maata’s diary, 10 April 1907: ...dearest K. writes “ducky” letters. I like this bit. “What did you mean by being so superlatively beautiful just as you went away. You witch; you are beauty incarnate."(8)

Installation view of Kōtiro, Emepaea (2021) George Watson, at Te Uru Waitākere Contemporary Gallery (2022). Photo: Sam Harnett

When I read Summer Idyll, I realise the dialogue mirrors that in your film almost exactly and think how easy it could have been to default to a tautological adaptation. Moyra points me to The Cinema (1926)(9), Virginia Woolf’s prescient essay that calls for filmmakers to go beyond literal book-to-screen translation, beyond banal symbolism and referents, and to consider the possibilities for cinema to assemble ‘Something abstract, something which moves with controlled and conscious art, something which calls for the very slightest help from words or music to make itself intelligible, yet justly uses them subserviently’; and with ‘a speed which the writer can only toil after in vain’.(10) (11) Roll my eyes at my own futile toiling. As if fulfilling Virginia’s call, your vignettes—mirages of idyllic pastoral domesticity—together digest the uncomfortable nuances of desire, colonial histories and snippets of a developing identity to the pulsing fervour of your soundscape. I see the land, as you unravel upon it your own—secrets of the girl, empire.

-Te-Uru-Photo-by-Sam-Hartnett_CIRCUIT-1650426880.jpg)